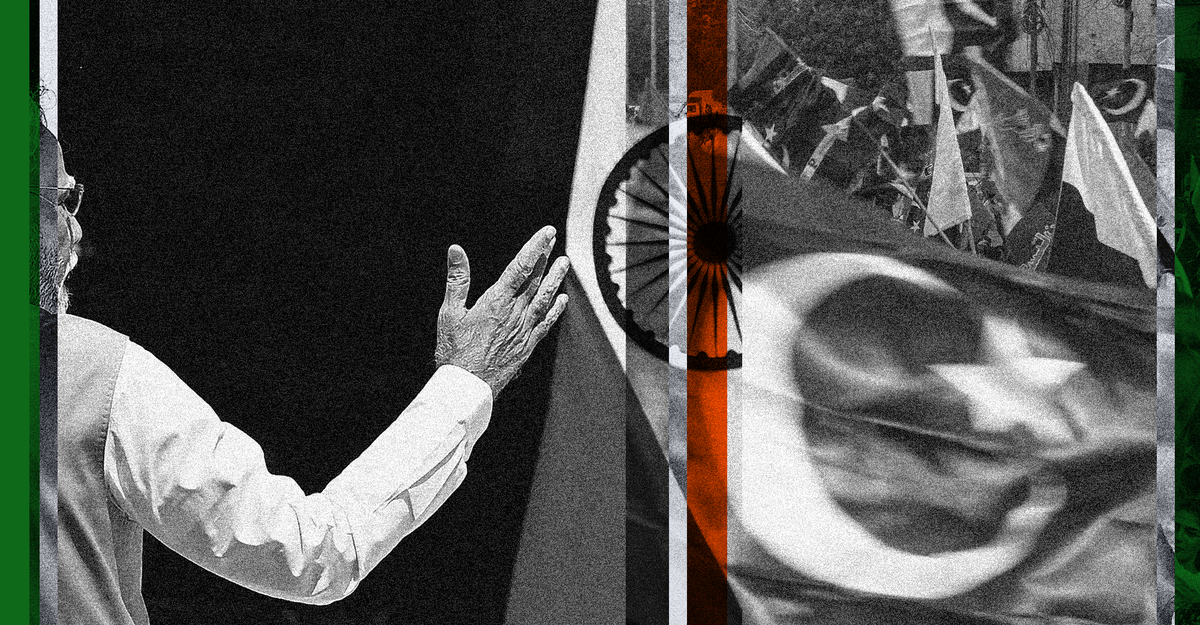

Why This India-Pakistan Conflict Is Different

May 8, 2025

New American Pope Blasted Trump and JD Vance Before Election

May 8, 2025Drawing on decades of frontline activism, Liz Theoharis and Noam Sandweiss-Back challenge poverty myths, uplift grassroots resistance and call for a bold reimagining of human rights in the U.S.

Mainstream media, conservatives and politicians want people to believe that the poor will always be with us. But it’s a lie.

In You Only Get What You’re Organized to Take: Lessons from the Movement to End Poverty, Presbyterian minister and long-time anti-poverty organizer Liz Theoharis and writer-organizer Noam Sandweiss-Back deconstruct this fallacy and present dozens of examples of organizing by poor people to win affordable housing, accessible healthcare, high-quality public education, a living wage, nutritious food and most importantly, dignity.

The book—part autobiography, part social history, part theological takedown of Christian nationalism and part call to action—not only offers concrete examples of on-the-ground organizing but also presents ways to reorient U.S. politics to meet the needs of every resident. Moreover, their intersectional approach brings disparate social movements together to organize for big-tent social justice, with an eye firmly placed on economic, political and human rights.

“When the emancipatory vision of human rights is brought directly into places and spaces of poor and dispossessed people, it becomes a transformative force,” they write. “Our power rests not in any one issue, but in the multiplicity of our demands and communities coming together. … Successful movements never just curse the darkness; they offer new ways of illuminating the future.”

Theoharis and Sandweiss-Back met with Ms. reporter Eleanor J. Bader to discuss the book, several weeks after the book was published in April.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Eleanor J. Bader: Liz, you’ve been involved in movements to end poverty for 30 years, since you were a college undergraduate. How did you get connected to the Kensington Welfare Rights Union and the National Union of the Homeless?

Liz Theoharis: I went to the University of Pennsylvania for college, and on the first day of my community service and social justice pre-orientation program, Ron Casanova, a representative of the National Union of the Homeless, and Kathleen Sullivan, a Penn alum who worked with the Kensington Welfare Rights Union, spoke.

Listening to them, I knew I’d found my home. Casanova told us that while there had been moments of homelessness before—cities with Skid Rows where people ended up when they were experiencing hard times—the extent of modern homelessness and mass evictions, along with the elimination of public housing, was unprecedented.

Sullivan added that the crisis was so new that the word ‘homelessness‘ had not yet been added to the spell-check function on computers—something I had noticed and been concerned by.

It was an incredible presentation. They had a clear understanding of the problem, and through their militant organizing, they offered real solutions. They insisted poor and dispossessed people had to get organized and unite across the lines that had historically divided them.

Bader: You essentially worked full-time as an anti-poverty organizer from that moment on, while completing your degree. How did you juggle everything?

Theoharis: In my life, then and now, it’s never been a question of finding balance, but really more about purpose. I was raised in a family where everything was about justice.

When I got to college, I was looking for a political and spiritual home, and I found it with unhoused organizers and welfare recipients. I got a campus work-study job at the community service office and used the office’s resources to support grassroots organizing across the city. I was also part of an AmeriCorps “service scholars” program.

I did both these jobs simultaneously and combined my interest in grassroots social activism with the academic requirements of the school; the papers I wrote and the research I did served both. In fact, the first research grant I was able to get gave us the money to buy the bolt cutters we used to move unhoused people into abandoned homes in Philadelphia.

But I’ve also never needed a lot of sleep!

Bader: One of the campaigns you write about involved unhoused people moving into properties that had been abandoned. Were these folks able to live in these homes permanently?

Theoharis: People rarely got to keep the houses they took over. More often, the people involved were given housing vouchers. Sometimes, when we did not win vouchers, we moved families from one abandoned home to another. And a few times, supporters came forward to enable us to buy what we called “human rights houses.” These gave us a base of operations for our organizing—shelter for a few families and a meeting space for our work.

Bader: Are people still moving into vacant homes and apartments?

Theoharis: 16 million empty units are estimated to exist throughout the United States. In various cities, there are five units for every unhoused person. Sometimes people stay or move back in to a house after an eviction or foreclosure. That’s been constant, but during COVID, people made overt what had been covert, moving into empty homes and declaring that they’d done so.

Rent strikes are another form of housing takeovers—when people refuse to pay rent they simply can’t afford or because of horrible conditions. We’ve seen an explosion in tenant organizing, which no doubt played a role in securing the federal moratorium on evictions at the onset of the pandemic. Rent strikes broke out and are continuing in places as diverse as Los Angeles, Brooklyn, N.Y., and Kansas City, Mo.

Noam Sandweiss-Back: It’s been inspiring to see how this organizing, in a time of rising costs and widespread economic precarity, has enabled people to break out of their silos. A lot of tenant organizers are clear that unhoused people are the tip of the spear, the leading edge, of the housing rights movement. Low-wage worker organizations inherently understand the importance of linking issues like living wages and housing, given how many low-wage workers are unhoused.

After the Supreme Court’s Grants Pass decision last summer, which accelerated the criminalization of homelessness, we’ve seen tenants’ unions, grassroots groups like the Nonviolent Medicaid Army, and many others working to defend encampments. We’re seeing the glimmers of what a more united movement could look like.

Now, the second Trump administration and numerous state governments are waging a war on “Housing First” policies and unhoused communities more broadly. This is a disaster, but it could also open new pathways for broader solidarity among the poor and dispossessed.

We need to build a consensus that acknowledges that we are in this together. This is the only way to ensure that the poor are not pitted against the almost-poor.

Liz Theoharis

Bader: There is a pervasive myth that there is not enough money for everyone to have housing, healthcare, good jobs, nutritious food and an education. How can organizers push back on this?

Theoharis: As a society, we throw away more food than it takes to feed the world, while half of all kids are food insecure. We have more empty houses than unhoused people, yet family homelessness has never been higher. Cities spend money “homeless-proofing” rather than using energy and resources to raise wages and end poverty.

The idea that there is “a culture of poverty” is repeated in the media, that the poor are lazy, inept or undeserving. One of the pivotal ideas in the book is that these myths exist and persist because they benefit the people in power. This is why we have to organize. We can’t rely on good policies alone. As we saw during COVID, good policies can be rescinded. But good policies alongside people organized to demand power can lead to lasting change.

The lesson for me is that we need change from the bottom up, not from the top down.

Bader: How can we help people understand their power to push for progressive social change?

Theoharis: Polling consistently shows that the majority of people across party lines agree that housing is a human right and believe that healthcare should be free. They support expanded voting rights and fair taxation, with the rich paying their fair share. I think it’s less about changing people’s minds on these issues and more about figuring out how to organize them into a force for change.

The last several decades have seen the right, and particularly Christian nationalists, become more powerful. We need to build a consensus that acknowledges that we are in this together. This is the only way to ensure that the poor are not pitted against the almost-poor.

The Trump administration’s current attacks on immigrants and LGBTQIA+ people, for example, are an attempt to divide us. The scapegoating of trans people, who make up a small number of the population and are disproportionately poor, is an attempt to go after the most vulnerable.

Bader: How do we build this cross-class, cross-race, multi-gender movement?

Theoharis: That’s the question of the moment. Part of it starts with believing that change is possible. People are organizing, and have always been organizing. But more people organize when it’s a matter of survival.

A lot of the people we organize with don’t consider themselves organizers, but they are leaders who are compelled to take action because for them it’s a matter of survival. When a mom advocates for her kids, she gets over the fear that people will see her as difficult or pushy. If you’re a worker who has done everything right but who still can’t catch a break, you don’t worry about being called an agitator. As Howard Thurman once put it, “When your back is against the wall, you have no choice but to push.”

Right now, there are a lot of people with their backs against the wall. And more people will likely join them, given the wide range of policy attacks, the cost-of-living crisis, and the very real possibility of a recession. In my experience doing very grassroots, anti-poverty organizing, there has always been a need for a big tent. We certainly need a broad and militant pro-democracy movement today. But where will that militancy come from? It will come from people whose lives are on the line. Those who have the most to gain from a big and risky fight. That’s the kind of leadership we need to follow right now.

When your back is against the wall, you have no choice but to push.

Howard Thurman

Bader: You write that anti-poverty organizing can be strengthened by using a human rights framework. Can you explain this?

Sandweiss-Back: Human rights have typically been understood in this country through a narrow focus only on international affairs or civil and political rights. Economic rights are almost always left off the table, even though there is an obvious connection between people’s economic flourishing and pro-democracy movements.

Eighty percent of the U.S. population will live under the poverty line at some point in their lives, and our nation’s life expectancy overall is actually declining. The fight for democracy is a fight for everything we need—voting rights, education, healthcare, housing, food, clean water and more.

And while Republicans are completely trampling on human rights, and Democrats often just paying lip-service to it, grassroots movements are seizing the very idea of human rights for themselves and breathing new life into it.

“Healthcare is a human right.” “Housing is a human right.” “Water is a human right.” These are the slogans of our times.

Low-wage worker organizations inherently understand the importance of linking issues like living wages and housing, given how many low-wage workers are unhoused.

Noam Sandweiss-Back

Bader: How do you keep the long-term goals in frame while also organizing for short-term victories?

Theoharis: We have to keep our eyes on the prize and imagine that massive change is possible, even when hope appears dim. At the same time, while we’re building toward this wider vision, we have to figure out what we can do in the here and now.

There is a lot of what we call “survival organizing” happening across the country, often totally under the radar. Mutual-aid groups and churches are feeding and housing their communities; LGBTQ+ people and women are figuring out how to get the healthcare they need; immigrant families are protecting one another from surveillance and deportation; community schools are stepping into the breach of our crumbling public education system.

Within these “projects of survival,” there is tremendous and untapped power. These efforts, when further politicized, organized and networked, have the potential to be a formidable base from which to anchor and fuel the pro-democracy movement.

Noam and I, as well as our colleagues at the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights and Social Justice, are using ‘You Only Get What You’re Organized to Take‘ to connect with community-based organizations, congregations, students and mutual aid groups. We’re touring around the country, calling for a Survival Revival.

Our vision is for a mass organizing drive that can link up and build on these emerging survival struggles—almost like the vast network that once made up the Underground Railroad. The goal is to build and sustain social change from the bottom up.

Great Job Eleanor J. Bader & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.