Despite Proven Fraud, Trump to Boost Payments to Privatized Medicare Advantage by $25 Billion | Common Dreams

April 8, 2025

No, President Trump, the Income Tax Wasn’t A Mistake. But It Was an Accident.

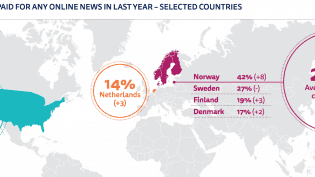

April 8, 2025Who actually wants impartial news?

Your first thought might be: everybody! After all, if news is meant to be a reflection of reality, wouldn’t you want the least biased version of that reality — the one that matches up most with the world around you? Even an outlet as partisan as Fox News understands the appeal of impartiality, branding itself “Fair and Balanced” for two decades. “Without Fear or Favor”; “Open to All Parties, but Influenced by None”; “All the News That’s Fit to Print”; “The Most Trusted Name in News”; “The Truth Is More Important Now Than Ever”: Each of these, in its own way, makes the claim that you’ll get the straight dope from our pages, print or digital.

But we all know that people’s behavior doesn’t always line up with their stated preferences. Most of the people who tune into cable news aren’t watching C-SPAN. And oceans of social science data have found that people prefer content that aligns with their own beliefs over content that doesn’t. What sorts of people are the most likely to prefer ideologically friendly content — not just prefer it but also say they prefer it?

One potential lens is power: who has it and who doesn’t. If you sit atop society’s food chain, perhaps you see impartial news as a potential threat — something that could mobilize the have-nots against you by exposing things you’d rather not have in the open. Or conversely, if you’re in a disadvantaged group, maybe you see “impartial” news as part of the existing power structure — telling stories that support the system that has left you at the bottom.

That’s the question explored by an interesting new paper just published in the International Journal of Communication. It’s titled “Who Wants Impartial News? Investigating Determinants of Preferences for Impartiality in 40 Countries,” and it’s by (deep breath) Camila Mont’Alverne (University of Strathclyde), Amy Ross A. Arguedas (Oxford), Sumitra Badrinathan (American), Benjamin Toff (Minnesota), Richard Fletcher (Oxford), and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (Copenhagen). Here’s the abstract:

Despite the centrality of impartiality for many journalistic cultures, and widespread support across audiences, there is still limited research about which aspects influence people’s preferences for impartial news. This article draws on survey data across 40 markets to investigate the factors shaping audience preferences for impartial news.Although most express a preference for impartial news, there are several overlapping groups of people who, probably for different reasons, are more likely to prefer news that shares their point of view: (a) the ideological and politically engaged; (b) young people, especially those who rely mainly on social media for news; (c) women; and (d) less socioeconomically advantaged groups.

We find systematic patterns across countries in preferences for alternatives to impartial news with greater support in places where people use more different sources of news and that are ranked lower in terms of quality of their democracies.

The first of those four groups is sort of a given. People who don’t have a strong personal ideology and who aren’t engaged with politics are unlikely to crave a strong partisan take in their news. After all, they don’t have one of their own!

But the other three — young people, women, and poorer groups — indicate that it’s the people with less power in a society who are more likely to see ideological news. If you’re a wealthy middle-aged white man, a huge part of the “impartial” media is aimed squarely at you — no need to seek an alternative. And the effect is even stronger in less-democratic countries where the state typically has a larger role in how the news gets reported.

Let’s look at the study. Its basis is the 2020 Digital News Report from Oxford’s Reuters Institute. (We wrote about it at the time.) That massive effort asked 80,000 people across 40 countries about their news consumption habits and preferences — 24 in Europe, 7 in Asia, 4 in Latin America, 2 in Africa (Kenya and South Africa), plus the U.S., Canada, and Australia. Journalists have endless debates about the meaning of words like “impartial” and “objective” and “balanced,” but it’s rare to have this large of a sample of how audiences think about them.

In general, mirroring debates that have taken place within and outside the profession of journalism, contemporary academic research has tended to cast the concept of impartiality in a somewhat more skeptical light, questioning the feasibility of achieving such an ideal or even the desirability of striving to do so. The idea that news ought to be reported neutrally, free of bias (objectively), is a relatively modern notion that has been variously attributed to different sociotechnical, economic, and cultural factors. Nonetheless, in increasingly pluralistic media environments, there is growing disagreement about what journalism could (and should) offer to societies or how journalists ought to properly perform their duties — roles that are often in tension.

News outlets exist, in one sense at least, to serve their audiences. But they also exist to serve their advertisers. And their journalists exist in an uneasy symbiosis with a community’s institutions — government, police, schools, business, civil society — which are the subject of much of their work. Does “impartial” news represent a purity of audience service? Or some triangulation of all the various power sources and elite stakeholders that interact with it?

(This paper expands on an earlier one by the same authors that found widespread support for “impartial” news in four countries — but also “no shared understanding of impartiality in practice…it is questionable whether audiences conceive impartiality in the same way that news organizations and journalism scholars.”)

The Digital News Report survey data being crunched asked people which they preferred when consuming news: “getting news from sources that share your point of view”; “getting news from sources that don’t have a particular point of view“; “getting news from sources that challenge your point of view”; or “don’t know.” The most popular responses overall were impartial (51%) and share-my-views (24%).

Within countries, they found the associations they expected to — that people were more likely to prefer ideologically aligned news if they were: (a) heavily engaged in politics who had a well defined ideology; (b) young; (c) heavily reliant on social media for news; (d) women; (e) less wealthy; or (f) less educated. Other than (a), those line up well with the idea that viewpoint-aligned news is more valued by those who feel disempowered within their society.

Interestingly, the United States was a standout on the issue of ideology — on both left and right. Among the 40 countries, U.S. liberals ranked No. 1 in how much extra support they gave to “impartial” media. This is almost certainly driven by the Trump I-era phenomenon of liberals viewing the news media as a counterbalance to his administration. It’s a contrast to the broader global tendency of people on the left being more skeptical of neutral news sources. (Think of what was called “alternative media” before the internet came along.)

Meanwhile, among the 40 countries, U.S. conservatives ranked No. 2 in how much extra support they gave to ideologically aligned media. In other words, they don’t trust the “fake news” or “lamestream media,” turning instead to Fox and its ilk. (Only Spain’s conservatives gave more support to ideologically aligned media.)

I emailed Mont’Alverne, the lead author, about this tension. Part of the issue, she suggested, is that people’s ideas of “impartial” news in the abstract don’t always line up with their real-world opinions. “It is possible, and probably what is happening in this case, that American left-wingers express preference for impartiality in general and in the abstract,” she emailed. “But when they are asked about it in a more concrete way, the limits of this preference become more visible.”

Those effects appeared within countries. But looking at nations as a whole, a different set of predictors appeared in the data. People were less likely to value “impartial” news in countries where: (a) journalists are perceived as being under the thumb of the state; (b) governments are less democratic and more authoritarian; and (c) where people on average consume more sources for news rather than fewer.

The first two make immediate sense. If your country’s “impartial” media is dominated by an authoritarian state, people are less likely to value it as a source of ground truth. The third may seem a little more puzzling. But countries where people consume more news sources are likely to be ones with a more vibrant news ecosystem, representing distinct points of view — meaning a politically aligned alternative is more likely to be available.

We find a negative correlation between the number of sources people use on average and the level of preferences for impartiality in that market, and a positive association with preference for news that shares their points of view. This might be explained by the fact that in markets dominated by fewer brands — often publicly funded ones such as the BBC — respondents in that market also tend to express higher levels of preference for impartiality.In the United Kingdom, where respondents used an average of four news brands, the lowest number across all countries, 62% of respondents said they prefer news with no point of view. In Kenya and Turkey, on the other hand, two of the countries with an above-average number of news brands used (13 for each), a much lower percentage said they preferred news with no point of view (29% and 34%, respectively).

In only four of the 40 countries did more people say they prefer news that shares their point of view to news with no point of view — Turkey, Kenya, Mexico, and the Philippines. All are countries where democracy traditions are, at best, challenged.

A couple variables didn’t have a significant impact on preference for impartial news: the degree of political polarization in the country, and whether people rely more on newspapers, TV, or cable news for their information.

People belonging to socially disadvantaged groups, such as women, younger, lower-income, and lower-educated participants, may find themselves less attached to journalistic norms that they do not feel have served their interests, which may be a reflection of grievances about journalistic shortcomings with respect to news that purports to be impartial but can come across as biased in favor of more privileged parts of society — especially when it comes to coverage of groups that are often stigmatized or ignored.For some of these audiences, expressing a preference for news that shares their points of view might be another way of saying they prefer news that portrays people like themselves more fairly.

…when respondents say they prefer news with “no point of view,” as embraced by relatively more advantaged individuals in most countries, it is possible that what they are expressing is a preference for news that mirrors and does not challenge dominant perspectives in society. These respondents might answer differently should they encounter “impartial” news that did not overwhelmingly reflect their own lived experiences or outlooks on the world.

All of which is to say that audience desire for “impartiality” is profoundly contextual — embedded in the particular political, social, and economic environment that people live in. It’s less an iron law of journalism than an incentive-driven response to conditions. “It is up to news organizations and journalists, therefore,” the authors conclude, “to evaluate which approach better suits their contexts.”

Mont’Alverne told me her main takeaway from the study was that people who want news with a point of view can do so for quite different reasons — from political motivations to feeling a lack of representation. “This reinforces the importance of actually considering what audiences think about journalism,” she said, “as it is common that people’s perceptions differ from assumptions academics and practitioners might have.”

Great Job Joshua Benton & the Team @ Nieman Lab Source link for sharing this story.