Jeffries Wants Dems to Put an End to the El Salvador Trips

April 30, 2025

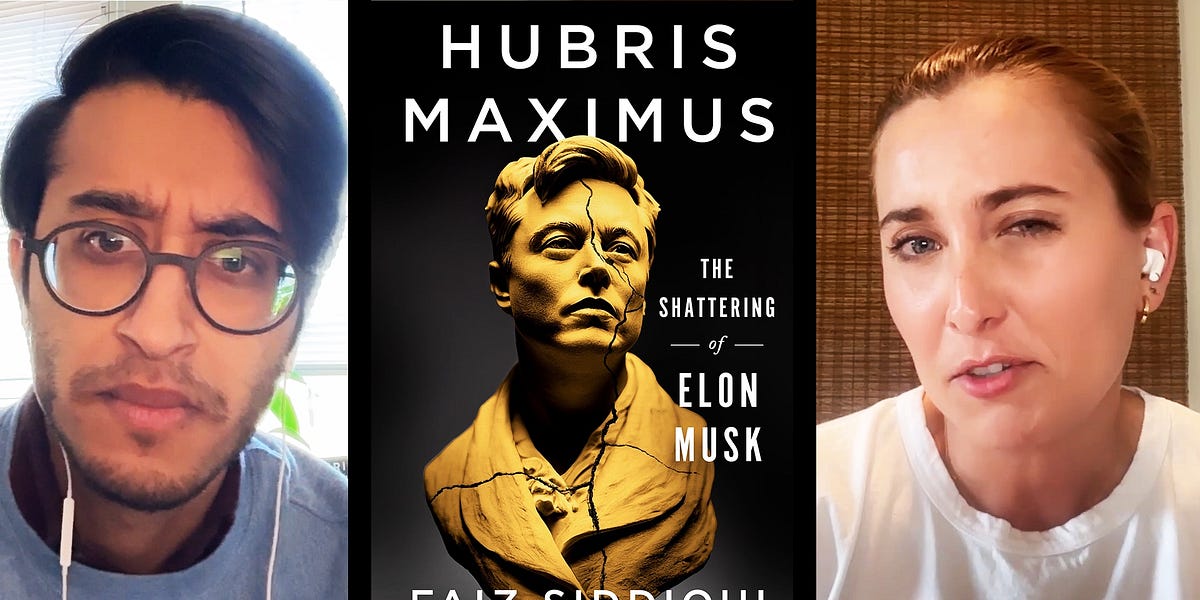

Elon Musk: Power, Paranoia, and Political Obsession

April 30, 2025A single mother on the verge of becoming a doctor confronts an inflexible loan cap that punishes low-income parenting students and threatens to derail years of sacrifice.

I’ve delivered babies in the hospital with breastmilk stains on my scrubs. I’ve charted patient vitals on four hours of sleep after staying up with my feverish toddler. I’ve studied for board exams in carpool lines, during lunch breaks at research meetings and in the dark while my son slept beside me.

For years, I’ve done everything we ask of future doctors. I’ve volunteered in underserved clinics, conducted maternal health research and mentored younger students. I’ve also raised a child largely on my own.

But now, one year from becoming a physician, I’ve been told I might not be able to graduate.

Not because of poor grades. Not because of burnout. But because I’ve hit a federal loan limit that doesn’t account for being a parent. Or being low-income. Or having no family left to call for help.

The federal government sets a lifetime borrowing cap for graduate and professional students: $224,000. That figure might seem generous, but it includes all loans from college and grad school combined. It doesn’t adjust for inflation. It doesn’t increase if you have a child. It doesn’t budge if you’re the first in your family to go to college, or if you’ve had to borrow just to get by.

And once you hit it, that’s it.

No matter how close you are to the finish line. No matter what it means for your family. No matter how much you’ve sacrificed to get there.

A loan cap that treats a childless student with generational wealth the same as a low-income, single mom is not equitable.

When I learned I’d hit that cap, I was devastated. I had carefully budgeted every year. My school’s financial aid office even adjusted my cost of attendance to account for my son’s needs—housing, childcare, food. I thought that meant the system was working for students like me. But no one told me the lifetime cap never changed. No one warned me it was approaching. And now, I’ve been advised to “try a private loan.”

But I’m a low-income student with no cosigner and no safety net. My parents are both gone. My credit took a hit when I was uninsured and had medical bills go to collections. There’s no one left to call. And private lenders don’t care how hard you’ve worked—they care about your credit score.

What kind of system brings a single mother this far, only to let her fall?

We tell young women to dream big. We tell first-generation students to reach higher. We tell moms they can do anything. But when we build policies that assume everyone has a financial cushion, that treat parenting like a liability instead of a reality, that penalize people for doing exactly what they’re supposed to—we’re not uplifting them. We’re quietly excluding them.

And the numbers prove it.

Each year, around 9,000 graduate students hit their federal loan limit—many in high-cost programs like medicine and dentistry. At the same time, nearly one in five applicants for Grad PLUS loans are denied, often due to past credit issues rooted not in irresponsibility but in poverty, medical debt or systemic inequities. Graduate students from low-income families, especially those who are first-generation or parenting, are the most at risk. And yet, they have the fewest safety nets.

Federal student loan policy treats all graduate students the same: independent, assumed to be financially self-sufficient and childless. There are no exceptions for parenting students. No increases in eligibility if you’re supporting dependents. No recognition that surviving without a family safety net comes at a real cost.

Meanwhile, undergraduate students whose parents are denied a PLUS loan automatically receive additional federal aid. The system recognizes that lack of family support means greater need. But for graduate students—many of whom are parents themselves—there’s no equivalent. If we were talking about an 18-year-old college freshman instead of a 30-year-old mom in medical school, I’d have more options.

This double standard reinforces outdated ideas about who belongs in higher education—and who deserves help to stay there.

When we talk about building a more equitable and inclusive healthcare system, we often focus on recruitment: how to get more women, more students of color, more working-class students and more caregivers into medical school. But we rarely talk about retention. About what happens when those students hit financial barriers that wealthier peers never have to think about. About what it takes to actually make it to graduation.

The truth is, it shouldn’t take tenacity and a GoFundMe to become a doctor.

Yet here I am—still fighting to finish. I’ve launched a fundraiser to cover the gap. I’m reaching out to legislators. I’m writing op-eds like this one. I’m doing all of it while parenting, studying, working and preparing for residency.

And I know I’m not alone. Across the country, there are thousands of student parents and low-income graduate students quietly disappearing from programs they once fought to enter—because our loan system was never built to include them.

Graduate students from low-income families, especially those who are first-generation or parenting, are the most at risk. And yet, they have the fewest safety nets.

We can fix this. The tools already exist.

Congress can raise the federal lifetime loan cap for graduate and professional students—and tie it to actual cost of attendance and inflation. They can restore subsidized loans for students in public service programs, so interest doesn’t accumulate while we’re still in school. They can create a built-in exception for student parents, recognizing that our expenses aren’t theoretical—they’re diapers and daycare and after-school snacks. And they can offer alternatives when Grad PLUS loans are denied—like increasing Direct Unsubsidized Loan limits or offering emergency grants.

None of this is radical. All of it is doable.

But first, we have to acknowledge the problem. We have to stop pretending that student loan policies are neutral or fair just because they apply equally to everyone. Equality and equity are not the same thing. A loan cap that treats a childless student with generational wealth the same as a low-income, single mom is not equitable. It’s exclusion by design.

My son has only ever known me as a student. He’s grown up visiting study groups, watching me present research, and clapping for me at white coat ceremonies. He knows his mom is working to become a doctor—not just for herself, but for others.

I want him to see me finish. But more than that, I want him to see a world where women like me are not the exception. Where we are supported, not just celebrated. And where no student has to choose between their dream and their dignity.

Great Job Tiffany Lemuz & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.