Bill Kristol: Hegseth Keeps Proving his Unfitness

April 21, 2025

Marjorie Taylor Greene Sends Sick Message After Pope Francis Death

April 21, 2025As the Trump administration slashes public sector jobs, Black women—who disproportionately rely on government employment for stability and upward mobility—face an urgent economic reckoning.

The sweeping federal job cuts taking place under the Trump administration are not just an attack on government effectiveness—they represent a direct threat to the economic stability of Black women, who have long utilized public sector employment as a pathway to financial security and upward mobility.

Now, as layoffs accelerate, Black women face a dual crisis: the loss of stable employment and the dismantling of one of the few sectors that has consistently countered private-sector inequities. These cuts risk unraveling decades of progress in building economic resilience for Black families and communities.

While public sector employment had declined sharply since the Great Recession, the Trump administration’s accelerated cuts represent a new, urgent threat. According to BLS data, federal government employment declined by 4,000 people in March and 11,000 people in February alone. As of this writing, federal rulings to reverse some of these layoffs have been overturned by the Supreme Court.

The federal government is the nation’s largest employer. As a result of these job losses, unemployment will rise not just in Washington, D.C., but also in various metro areas.

These discharged government workers are now entering an uncertain job market where reemployment elsewhere may be a slow and painful effort; for Black workers, who are always hardest hit in economic downturns, this will likely hurt the most. Efforts to cut government employment are in line with Republican tropes around the need for “small” government and depictions of federal spending as inefficient and wasteful, even when data shows Republican administrations have added more to national debt than Democratic administrations.

Among the general public, psychologists have documented that while there are some positive stereotypes associated with specific public sector workers generally (including nurses, teachers and fire fighters), there are fewer with public sector workers overall. Some conservative pundits have characterized government workers as “lazy” and even “parasites,” terms that are linked to anti-Blackness.

Government employment is significant for both society and workers. Workers carry out the critical functions of the public sector that serve U.S. residents. Government employment is known to be more supportive than the private sector, with more benefits and comparatively more job security, including during tumultuous times such as the height of the COVID-19 pandemic; in fact progressive economists and politicians have called for a federal jobs guarantee to make sure that people who want a good job can have one. These government jobs would serve as competition to compel the private sector to do better.

For Black workers, especially Black women, government employment is particularly meaningful.

According to data from 2022 Current Population Survey (CPS) of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 22 percent of Black women in the labor force are government employees—a rate higher than that of workers overall (15 percent), as well as 15 percent of Black men, 14 percent of Latinx women, 8 percent of Latinx men, 18 percent of white women and 12 percent of white men.

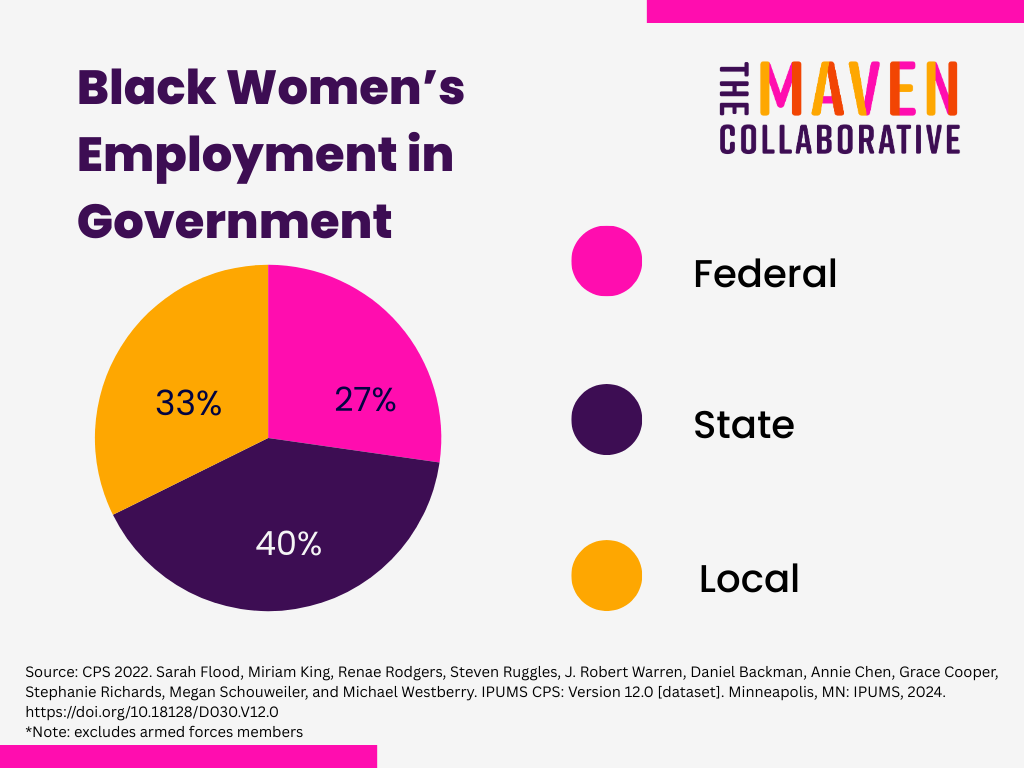

Of Black women employed by the government, 27 percent are federal employees, 40 percent are state government employees, and 33 percent are local government employees.

Black women have historically faced discrimination in the workplace that includes overrepresentation in lower quality jobs (also known as occupational segregation), even taking education into account, lower wages and fewer benefits.

The public sector is known to be more “egalitarian” for Black women in a few ways:

Wages

Black women are paid higher wages as government workers than in the private sector, with federal government workers being paid the most.

Bargaining Power

Black women with government jobs are more likely to have union coverage which means more bargaining power and protections (37 percent of Black women government workers have union membership or are covered by a union versus 7.8 percent of Black women employed privately).

Health

Black women with government jobs are more likely to have any health insurance coverage than those who are privately employed (96 percent versus 91 percent).

Black women who are government employees are more likely to be included in an employer health insurance plan (89 percent versus 76 percent). The cuts to federal jobs compounded with likely cuts to Medicaid could have devastating impacts.

Black women with government jobs are more likely to report having “excellent” or “very good” health than Black women who are privately employed (62 percent versus 57 percent)

Economic Well-Being

Black women with government jobs are more likely to be included in a retirement plan at work (59 percent compared to 30 percent of Black women in private employment). Rates are high for federal government workers (61 percent), state government workers (54 percent), and local government workers (64 percent).

Black women with government jobs are less likely to be below the poverty level than those privately employed (3.1 percent versus 7.7 percent) and less likely to be within 100-124 percent of the poverty level (2.7 percent compared to 4.4 percent).

While Black women with government jobs are paid more than Black women who are privately employed, Black women are still paid some of the lowest wages among government workers—$56,000 annually compared to $60,000 for Black men, $58,000, for white women and $75,000 for white men, according to 2022 CPS data. As federal government workers Black women are paid $66,000 compared to $80,000 for white women and $92,000 for white men. Black women are also less likely than white men to be included in a retirement plan at work (59 percent compared to 69 percent of white men). Researchers have documented occupational segregation in government work that may explain some of these findings.

Still, as noted above, government work is better for all workers, including Black women. History shows that Black workers, including Black women, fare worse than others during economic downfalls, including in downturns to public sector employment. This means the attempts to gut government employment could have disastrous impacts on all government workers, recipients of public services and especially Black women and their families for whom they bear significant home-based and extended family caregiving responsibilities.

Gutting these jobs isn’t just about budgetary concerns; it’s about perpetuating systemic inequality and undermining the progress Black women have fought so hard to achieve. As history has shown, economic downturns and public sector job losses disproportionately harm Black workers, unraveling their economic stability and widening the persistent income and wealth divide.

This time calls for counter-narratives that focus on the essential role of government and public sector workers in supporting economic security. It’s time to organize and advocate for elected officials to protect these vital jobs and services, while amplifying the voices of Black women who have dedicated their lives to public service. We need more investment in public services that benefit all communities, not less. The economic security of Black women is inextricably linked to the well-being of our society, and we must act now to protect it.

Great Job Ofronama Biu & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.