Richard Chamberlain, TV actor who starred in ‘Dr. Kildare,’ dies at 90

March 30, 2025

Bulwark on Sunday: The People Are The Only Solution to Trump

March 30, 2025

On February 25, 2025, Warner Bros. Games — the gaming subsidiary of Warner Bros. Discovery — announced that it was shutting down Monolith Productions, along with two other game studios. In an official statement sent to gaming news sites, the layoffs were justified by Warner Bros. through the same clichéd business-speak that always accompanies such shutdowns: the need for “a strategic change in direction” and a renewed focus on “high-quality games.” Of course, there is nothing in this statement about how laying off hundreds of artists, programmers, and designers would help them to achieve this lofty goal.

Such contradictory statements are typical of many game publishers that fail to understand the work of their own studios. In May of last year, Microsoft shut down Tango Gameworks, the developer of the British Academy Film Award (BAFTA)–winning rhythm action game Hi-Fi Rush. According to a report in the Verge, a day after its closure, a Microsoft executive said, without a trace of irony, “We need smaller games that give us prestige and awards.” Electronic Arts keeps laying off workers at BioWare, after years of forcing the once-storied role-playing game developer to work on middling online experiences. Thus Warner Bros. is not unique — there is a disturbing trend in the games industry of publishers destroying studios doing original, notable work. This not only harms workers but limits the potential of what games could be.

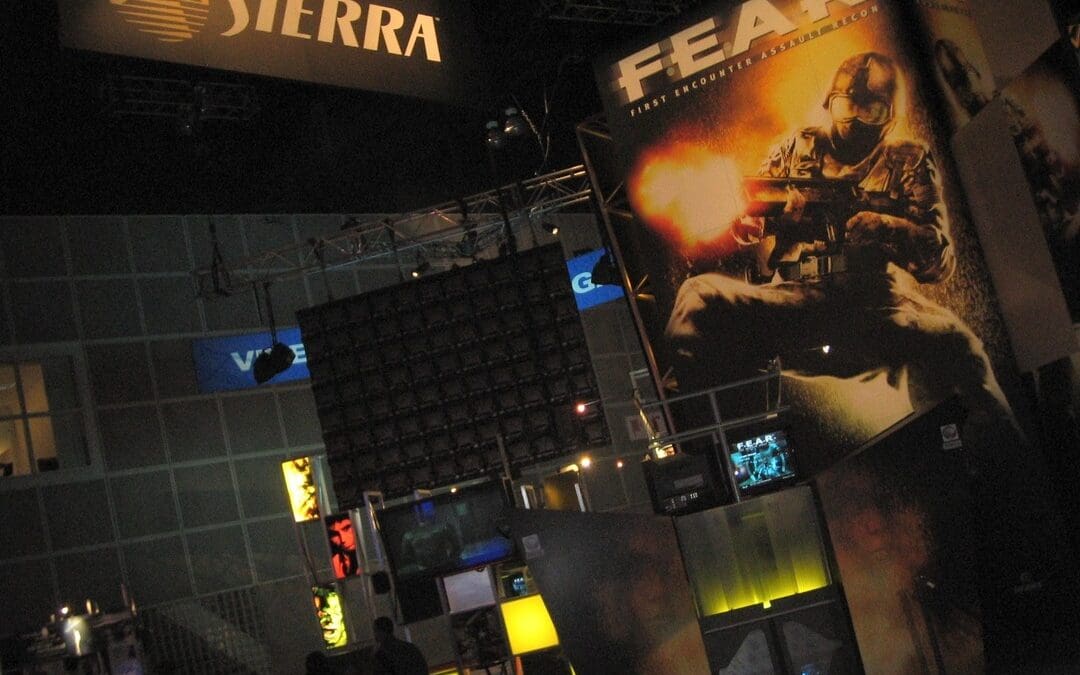

Monolith understood that potential, specializing in genre mash-ups that were offbeat and often original. In addition to the pulp delights of Blood, there was The Operative: No One Lives Forever: a 1960s stealth spy thriller that mixed its memorable action set pieces with comedic conversations from aggressive monkey salesmen and henchmen who wanted to go to band practice. In F. E. A. R., Monolith improbably mashed together scenes of horror straight from The Ring with frantic shoot-outs out of John Woo’s The Killer and Hard Boiled. Many gamers today likely know Monolith best for its Lord of the Rings game Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor and its “Nemesis system,” which let you build rivalries with individual orcs and change the balance of power among their disputatious clans based on your in-game successes and failures.

While it’s quite baffling that Warner Bros. would close a studio with which it had such a productive partnership, this is not the first time Monolith suffered at the hands of publisher malfeasance. There are many frustrating incidents across the company’s thirty-year history — incidents that shed light on the political economy of an industry that not only exploits game workers but has also contributed to the overall cultural marginalization of games.

There was a time when more experimentation with games seemed possible, and Monolith Productions was an important part of that. In the rapidly expanding PC industry of the 1990s, there were three things that seemed to give a game developer a relative degree of autonomy in a publisher-dominated games industry: developing your own technology, developing original games, and having those games become hits that lead to franchises.

Monolith was able to build its own technology — all of its 3D action games were built on a game engine it designed called LithTech — and it had a proven track record of original work. However, it never quite achieved the same level of clout as rivals like Epic Games or Valve Software. A big reason for this was that the studio was continually undermined by some truly awful game publishers.

The development of Blood II is a classic example of publisher meddling. GT Interactive, Monolith’s publisher at the time, wanted a sequel to Blood as soon as possible. Unfortunately, this meant a relatively short development time — that way the publisher could get it on store shelves before Christmas 1998. Because of this, GT Interactive was only willing to fund eleven months of development and shipped the game despite knowing it was not fully ready for release.

But the problems did not end there. In an interview, then Monolith CEO Jason Hall admitted that “it would have cost Monolith close to $105,000 a month to fix Blood 2 properly,” but GT refused to fund these fixes. Furthermore, due to GT’s ownership rights over the Blood franchise, Monolith did not receive any royalties from the release of Blood II, forcing it to focus on other things to survive. Monolith would live to see another day by licensing its game engine technology and striking a deal with a different publisher. However, this did not spell the end of its publisher headaches.

Monolith seemed to enjoy a better relationship with Fox Interactive. However, Fox Interactive was eventually acquired by another game publisher, Vivendi Universal Games (VUG,) which took over the publishing of Monolith’s first-person shooter F. E. A. R. VUG was the gaming offshoot of the French investment company Vivendi, notorious for water privatization in the developing world, to give some idea of its character.

In a 2014 interview on the podcast Tone Control, lead designer Craig Hubbard revealed that the name F. E. A. R. was not Monolith’s idea but was demanded by VUG for trademark reasons. This came back to haunt Monolith after it was acquired by Warner Bros. and wanted to make a sequel. Monolith had the rights to the story, characters, and setting but not to the name F. E. A. R., which was owned by VUG. Eventually Monolith got the name back — but not before VUG put out two cash-in expansions that received middling to negative reviews and alienated some of the original’s fans.

Since game publishers often front the costs of development, distribution, and marketing, they hold enormous power over developers. By meddling in Monolith’s development processes, GT Interactive and VUG demonstrated a willingness to undermine a studio they invested in rather than give it creative freedom and control. Interference is unfortunately common due to major game publishers wanting to cash in on the latest trend. When that doesn’t pay off, game studios are closed. Publishers can afford to be somewhat indifferent about studio closures because onerous intellectual property regimes ensure their control extends even after a studio’s dissolution.

After reading this article, you might be tempted to pop over to Steam or GOG.com to pick up some of the games I’ve mentioned. But one game is conspicuously absent from these digital storefronts: No One Lives Forever. No One Lives Forever is remembered quite fondly as one of the best games of the early 2000s, but due to various contentious copyright claims it has become “abandonware.” Abandonware is the term for a piece of software that is completely abandoned and unsupported by a publisher. This does not mean, however, that copyright is null and void. No One Lives Forever is illustrative of the kind of legal limbo that abandonware games often become stuck in. Kotaku’s Kirk Hamilton provides a concise breakdown of No One Lives Forever’s copyright woes:

NOLF was made using a framework called the LithTech engine, which is also now owned by Warner Bros. However, the first game was published by Fox Interactive, and there’s a question of whether 20th Century Fox or even Activision might have partial rights to the series, due to Activision’s 2008 merger with Vivendi, a separate media company that had acquired Fox Interactive in 2003.

Are you following all of this? As Hamilton goes on to detail, Night Dive, a game studio that specializes in remastering and rereleasing classic games, has experienced nothing but headaches in trying to get a deal going with the publishers. This has only become more complicated because in the decade since Hamilton’s article’s publication, Fox has been acquired by Disney and Activision has been acquired by Microsoft.

The same fate awaits another core technology developed by Monolith — the aforementioned “Nemesis system” used in Shadow of Mordor. Unfortunately, the technology behind this procedural form of storytelling was patented by Warner Bros. This translates to no other studio being able to use this system in their games or even developing something similar for fear of receiving a lawsuit. A historical counterexample to this kind of technological lockdown is Doom and Quake developer id Software, which has open-sourced past iterations of their id Tech game engine. This has led to the creation of hundreds of new games and levels and new ways to play as well as continued community support.

Despite various tribulations, Monolith was able to survive more than thirty years in an industry where many publishers do not care about the workers responsible for their existence. Furthermore, these same publishers do not care about games as a medium or art form. Many of them are perfectly content to have innovative technologies and original concepts stagnate. Better to lock things down than to have someone else threaten your market share.

Like many workers before them, the employees of Monolith fell victim to a callous group of executives whose only concern is making the next quarter. Although unionization efforts are growing, game workers still face many challenges, particularly when tens of thousands are being sacrificed for short-term gain. It is only when game workers are fully organized that they will be able to beat back the forces that want to absorb their creative efforts — and leave nothing else behind.

Great Job Alexander Ross & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.