Dept. of Education plans to slash nearly 50 percent of its staff, paving the way for the agency’s closure

March 11, 2025

As Trump Courts Putin, Russians Keep Trying to Kill Americans

March 12, 2025ON FEBRUARY 7, PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP fired Archivist of the United States Colleen Shogan, on the job for only 632 days, without notice or cause. By statute, Deputy Archivist William “Jay” Bosanko automatically became the acting archivist, leading the National Archives and Records Administration. Less than a week later, the White House sent Jim Byron, the president and CEO of the Richard Nixon Foundation—one of the private nonprofit groups that builds and supports presidential libraries—to give Bosanko an ultimatum: resign or be fired.

Bosanko resigned, and the Trump administration has made temporary arrangements for operation of NARA, designating Marco Rubio the acting archivist (his third concurrent role, in addition to secretary of state and administrator of whatever husk remains of USAID). The president is expected to nominate a new archivist, but the timing is as yet unclear.

By law, that appointment must be free of political affiliation and made on professional qualifications alone. But this has not stopped some prior presidents from nominating—or tentatively floating—individuals clearly for their politics. And in the agency’s history of eleven permanent and seven acting archivists, the two confirmed archivists who have been the most explicitly political turned out to be the most disastrous: Allen Weinstein and Don Wilson.

If their tenures are any indication of how badly a politicized appointment can damage the agency, the current widespread alarm among stakeholders and NARA employees is well founded.

IN NARA’S NINETY-YEAR HISTORY, only one other president has removed an archivist: President George W. Bush forced the eighth archivist, John Carlin—whom President Bill Clinton had nominated almost a decade earlier—to resign so that Bush could nominate the already-vetted and reliable political operator Allen Weinstein.

According to Carlin, the push to get him out began early, during the 2000–01 transition between administrations. “A member of the transition staff called,” Carlin told me in a phone interview. “And he asked when I would resign. I said I wanted to stay. I explained the law—that the president could replace me, but he’d have to communicate to Congress as to the reasons why. I never heard back from that young man.”

A few years later, though, Carlin got another call—this time, from White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales. “He said, ‘I’m just the messenger, but the folks here would really like you to resign,” Carlin recalled.

Carlin again rebuffed the White House’s call for his resignation.

“I repeated what I’d told the transition team, about my desire to remain, and about the law. And I assumed that Gonzales would want to follow that law. So that was that.”

However, that wasn’t that. Months later, Gonzales called him again, more insistently. “Gonzales made it clear by telling me, ‘It’s starting to get rough here, John, and I just want you to know it would be a lot easier on you, no hassle, you know . . . if you’d just resign.’”

When asked what he thought it meant when Gonzales said it would be “easier on” him, Carlin replied that he didn’t know. “They were already working on the person to replace me well before they asked me to resign. And it turned out that was Weinstein. They wanted me gone so they could replace me with him.”

More than two decades later, it still puzzles Carlin that he was, essentially, fired without cause. And it surprised him to have received such pressure to resign from Gonzales.

“I got along with him pretty well,” Carlin recalled. “We had connected personally a few times. We knew each other. It wasn’t like he was calling someone his staff had to tell who I was.”

Carlin said that in the third call, he repeated the requirements of the law to Gonzales, and that he planned on remaining in the job. But Gonzales was firm.

“Then I decided they really wanted me out,” Carlin said. “And I’d almost completed the ten years I’d said I’d do when I took the job. So I cooperated. The Bush administration was otherwise generally good to me.” He resigned in February 2005.

When reached by phone for comment, Judge Gonzalez, now the dean of the Belmont University College of Law, said, “I can’t recall those conversations. And I can’t remember any negative feelings about [Archivist Carlin]. Out of the blue, I’d have to say he was really good.”

Gonzales went on to say, “I don’t doubt it happened if that’s what he remembers. I can’t confirm it, but I have no reason to believe it isn’t true.”

When Senators Carl Levin and Dick Durbin revealed during Weinstein’s confirmation hearing that the White House had pressured Carlin to resign, it made news, and caused a stir in the stakeholder community. But Weinstein, who in 1978 made his name as a historian of the Alger Hiss case, had spent the next two decades promoting democracy internationally, hobnobbing in foreign policy circles, and establishing relationships with powerful government figures. He consequently enjoyed long friendships with many in the Senate, who had lavishly praised the president’s selection. While his nomination expired, and the White House had to resubmit it a few months later, as it had done with Carlin the Senate quickly confirmed Weinstein by unanimous consent.

Weinstein, who over a long career of relatively brief jobs that had ended abruptly and without clear public explanations, validated the faith the White House had in him by consistently supporting the Bush administration’s positions rather than be an objective arbiter.

But his tenure turned out to be a disaster for another reason: As I was the first to report, Weinstein was a longtime serial sexual predator who attacked and harassed NARA and National Archives Foundation staff (as well as women in organizations prior to and after his time in office). After intervention from then-White House Counsel Fred Fielding, the FBI and the Department of Justice discreetly ended an investigation into Weinstein, forestalling certain prosecution, and Bush allowed him to resign quietly in December 2008, citing “health reasons.”

WEINSTEIN’S MESSY DEPARTURE from NARA was covered up at the time, but the exit in 1993 of one of his predecessors, Don Wilson, the seventh archivist, was much more of a public spectacle: Wilson resigned under a cloud of multiple investigations over his handling of the agency.

The story of how Wilson came into the job helps explain some of what went wrong during his tenure. Just a few months after his party’s loss of 26 House seats in his first midterm election (while maintaining a majority in the Senate), Ronald Reagan was having a hard time nominating a new archivist. Rumors were circulating he would replace the incumbent, Robert Warner, with a political appointee more to the administration’s liking. Warner, a former president of the Society of American Archivists and a respected historian, had become archivist less than three years earlier, just four months before Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election.

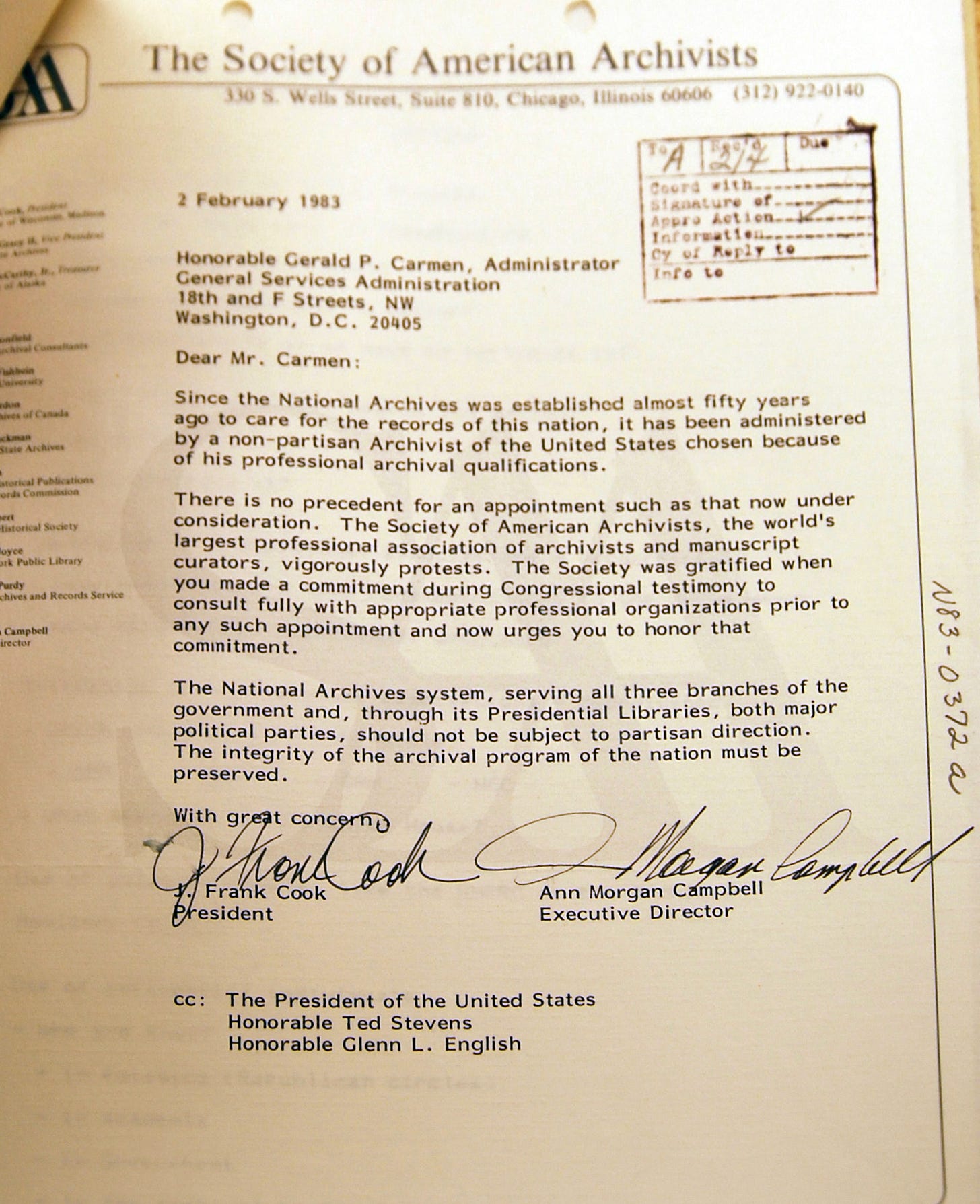

In early 1983, the White House recalled Richard F. Staar, the chief U.S. representative to the Mutual and Balanced Force Reductions Negotiations in Vienna. As word spread that Staar soon would be Reagan’s nominee to lead what was then known as the National Archives and Records Service (under the General Services Administration), concerns grew that the long-nonpartisan position—held, until Warner, by career NARA archivists—would become politicized.

Individuals and professional organizations wrote to the White House to protest Warner’s possible removal and to urge the president not to propose a political nominee. In the end, Reagan never put forth Staar’s name, but he didn’t drop the idea of naming his own archivist.

Warner retired in April 1985, when the agency split from the GSA (due in no small measure to his significant efforts calling for the change). The nomination for the first archivist to lead the newly re-independent agency garnered a lot of attention. Reagan had signed into law the National Archives and Records Administration Act of 1984, which mandates that the archivist “shall be appointed without regard to political affiliations and solely on the basis of the professional qualifications required to perform the duties and responsibilities of the office.” With the agency finally out from under direct political control, stakeholders were watching to make sure that the post, with its important, nonpartisan responsibilities, not become politicized.

The administration’s first choice, Peter Duignan, a senior fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution, was seen by many as too political even before he was formally nominated (which he never would be, due to concerns about a likely rocky confirmation process).

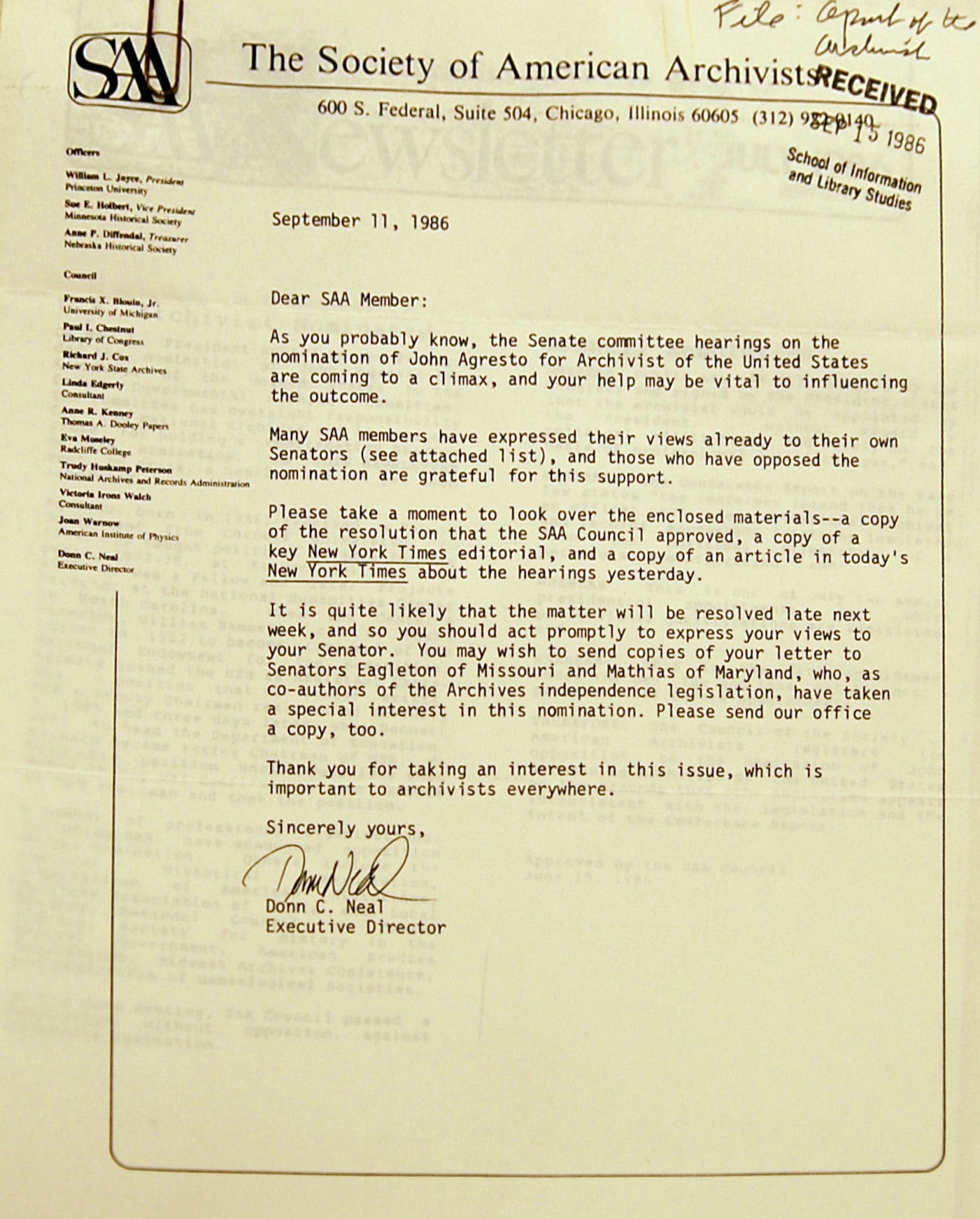

It wasn’t until May 1, 1986—more than a year after Warner retired, while career NARA official Frank Burke had served as acting archivist—that Reagan nominated John Agresto. A protégé of former National Endowment for the Humanities chairman and then–Secretary of Education William Bennett, Agresto also was challenged as being too political.

The avalanche against Agresto was considerable. Professional organizations publicly and forcefully protested his nomination. Thirteen groups representing NARA’s main records users formally opposed him. The Society for History in the Federal Government warned that his confirmation would “decisively impede the aura of impartiality and professional detachment required for such a position of national trust.”

Agresto’s contentious confirmation hearing in the Senate lasted three days. When the Committee on Governmental Affairs met in October to vote, with his rejection the likely outcome, not enough Republican senators were present for a quorum, and the Senate did not consider his nomination before adjourning for the midterm elections. While the White House vowed to resubmit his name, and even considered installing him via a recess appointment, Agresto was done.

The next choice would have to be nonpolitical—or, at least, be viewed as such. Reagan insiders wanted someone they could trust to be loyal, someone on whom they could count as much as they had known they would have been able to count on Agresto. Among the reasons they were concerned about who the next archivist would be: They were thinking ahead to the eventual creation of Reagan’s presidential library, and had in mind that he was the first president subject to the new Presidential Records Act. But the president couldn’t afford yet another nomination scuttled due to the appearance of partisanship.

So he turned to a candidate who had applied for the job the previous fall: Don Wilson, then the director of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

The White House presented Wilson to the public as nonpolitical, a career NARA employee. In fact, he couldn’t have been more political. His application for the job—which was not released at the time, nor since, but which I accessed at the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor—went out of its way to indicate to the Reagan team that he was aligned with them.

It included, along with a standard resume, cover letter, and personal/professional references, three additions: a note reassuring the White House about his Republican politics; a list of political references; and a number of strong letters of recommendations from well-known Republican politicians. Even Wilson’s “personal/professional” list, though, was full of political references, including former President Gerald R. Ford; David and Julie Nixon Eisenhower; Marlin Fitzwater, who was then the press secretary for Vice President George H.W. Bush; Lt. General Brent Scowcroft; and the heads of the private Hoover and Reagan Presidential Library Foundations.

These materials make clear that Wilson knew how important the politics surrounding the nomination were to the Reagan White House, and knew it well before the Agresto nomination imploded, as Wilson had sent in his application months earlier, on October 31, 1985. In the note included with his application, addressed to the Office of Presidential Personnel, after touting his work as director of the Ford Library—and pointing out his previous successful experience working with “institutions operated through a combination of public and private funds along with affiliated foundations or boards”—Wilson wrote,

What does not precisely appear in the accompanying material are my interests and activities in the political sector. As a college student, I became actively involved in then Republican Congressman William Avery’s campaign for the governorship of Kansas (successful). My father served a [sic] Governor Avery’s regional campaign manager for North Central Kansas.

While on the staff of the Eisenhower Library, I was elected to the Abilene City Commission with strong local Republican party support. Although this was a non-partisan election, I was endorsed by the Republican leaders in Abilene and led all candidates in votes received. I served on the five member governing commission until moving to Wisconsin in 1978. Also, in late 1977 and 1978, I was an advisor and volunteer for Deryl Scheuster [sic] in his unsuccessful bid for the Republican nomination in Kansas for the United States Senate.

I have enclosed a substantial list of references who may be contacted and who are knowledgeable about my skills and background. I would anticipate no difficulty in receiving Senate confirmation. A number of members of Congress have already indicated support if I were to be nominated.

Wilson’s two separate lists of ten references were titled, respectively, “Personal/Professional” and “Political.” The latter included three sitting and two former senators, two representatives, one lobbyist, and one pollster—all Republicans.

On August 14, 1987, Reagan formally nominated Wilson to be the archivist of the United States. The Senate confirmed him without incident a few months later.

Some hailed the political independence of the new archivist. At Wilson’s swearing-in ceremony in the Rotunda of the National Archives Building in Washington, his predecessor, Robert Warner—who knew Wilson well, and was aware of the contents of his application—said, “The installation today of a worthy candidate who fully meets the terms of the law marks the true conclusion of the Archives independence movement.”

Wilson promised “aggressive, creative, professional leadership” as archivist. President Reagan spoke at the ceremony, saying Wilson was “more than qualified . . . for this high post, both by academic background and years of experience.”

And to administer the oath, Wilson chose a different politician—a former White House chief of staff who was one of the sitting members of Congress who appeared on his “Political” reference list: Rep. Dick Cheney.

LET’S SKIP AHEAD A FEW YEARS. By the fall of 1992, Don Wilson’s time in the job was running short, and he badly needed an exit strategy. Instead of being the rewarding capstone to his career, his relatively brief tenure had been—at best—controversial. From his clashes with Congress and reportedly dysfunctional management style to his improper handling of the hiring and supervision of NARA’s inspector general and his favoring of presidents in records disputes, Wilson generated more problems within and for the agency than perhaps all of his predecessors (or successors) combined. He had been investigated by, or was still actively being investigated by, the Senate, the Office of Special Counsel, the President’s Council on Integrity and Efficiency in Government, the Office of Personnel Management, and the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services, not to mention proceedings in the courts.

Government investigators had found Wilson to have failed in his managerial, administrative, legislative, regulatory, financial, and ethical responsibilities. In some cases, they determined he had acted inappropriately; in others, that he had improperly delegated responsibility and authority to his subordinates, and then failed to supervise their actions.

In 1991, the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs began an investigation of NARA’s management practices. The probe took a year, and included the work of the FBI, the OSC, and other offices. Wilson’s term was deemed to have been such a failure and he himself so missing from responsibility and accountability that the senator chairing the committee dubbed him the “Absentee Archivist.” (Years later, in a 2015 oral history for NARA, Wilson dismissed the characterization as just a “planted story.”)

On the eve of the 1992 election, the committee issued its report, Serious Management Problems at the National Archives and Records Administration. It concluded, “Archivist Don Wilson failed to exercise care and diligence in fulfilling his responsibilities” and recommended,

The President of the United States should undertake a review of the actions of the Archivist of the United States in connection with the activities detailed in this report, including but not limited to questions concerning compliance with the Inspector General Act (as amended) and the exercise of administrative and management responsibilities.

Also in the 2015 oral history, Wilson said at that point he was,

. . . really under the gun and, right after the election I was in this dilemma. I didn’t really want to continue serving in that kind of environment. At the same time if I resigned I politicized the agency because it meant each future Archivist would have to resign under a new administration. Basically, they can interpret it that way. If I didn’t resign, I was going to get a handful of trouble.

The 1992 presidential election saw a Republican incumbent defeated by a Democrat who would soon take office and possibly clean house. So after five years on the job, Wilson really needed a way out. With a soft landing, if possible.

It was in that climate and mindset that Wilson decided to do a political favor for a powerful figure. Late on the night of January 19, 1993—just hours before the new president was to be sworn in—Wilson signed away important presidential records while seeking a new job.

FOR DECADES, NARA HAS PROVIDED assistance to presidents and their foundations in planning their libraries. But more than any archivist since the first, R.D.W. Connor, helped President Franklin Roosevelt plan his library, Wilson had eagerly sought to aid President Bush in building his.

Wilson received and evaluated all proposals from institutions vying to land the library. He paid site visits to the three finalists. He strongly influenced Bush’s final choice of Texas A&M University. In fact, records from the Office of the Archivist that I obtained via the Freedom of Information Act show that, during the final phases of the process, Wilson provided A&M officials with more detailed information on Bush’s personal criteria than he did the other finalists, the University of Houston and Rice University.

Once the site selection had been made, Wilson offered to inform the losing candidates, so that Bush wouldn’t have to make those calls himself.

Wilson had worked closely with the H.W. Bush White House for years, influencing the planning and steering of the process. So it was perhaps not a stretch for the administration to reach out to him, shortly before Bush left office, to ask for one more favor. And, given Wilson’s dire circumstances—if he remained on the job, incoming President Bill Clinton would almost certainly fire him—it’s understandable, if not forgivable, that he said yes.

Here’s the story: Since the end of the Reagan administration, journalist Scott Armstrong, along with the National Security Archive (NSA) at the George Washington University and other organizations, together had been fighting a battle to preserve backup tapes of the White House email system known as “PROFS.” The most important and controversial records in that system related to the Iran-Contra affair.

The tapes were important to both the investigations of the scandal and to history in general. At several times between 1989 and 1993, the Reagan and Bush administrations tried to destroy them. It was only because of the ongoing series of legal actions—restraining orders, decisions that the emails were official records and that the White House must preserve the tapes—that they survived so long. Even in the face of unambiguous court rulings, though, the White House continued to try to get rid of them.

With thirteen hours left in Bush’s term, Wilson signed a secret agreement granting Bush exclusive legal and physical custody of the White House email tapes. A federal judge later declared it illegal, calling Wilson’s actions, “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, and contrary to law.”

Three weeks later, Wilson announced that he would resign the office of archivist of the United States and begin his new position as executive director of the George Bush Presidential Library Foundation at Texas A&M University. He denied that his appointment to run the foundation, at $129,000 a year (about $286,000 in today’s dollars), was the result of a quid pro quo or had anything to do with the tapes agreement.

DON WILSON WAS THE FIRST permanent archivist that a president had nominated under the 1984 law, and the last of all confirmed archivists in the agency’s history to have been in fact an archivist by profession, or to hold any of the direct statutory qualifications that the drafters had envisioned.

Yet Wilson left the National Archives weaker as an agency, its reputation damaged, and its credibility as a nonpartisan administrator of federal and presidential records laws in serious doubt. And he ushered in a new era of strong politicization, deference to presidents and their private foundations, and acceptance of rewritten history in NARA’s museums that continues unabated today.

One of the glaring ways this can be seen is that the new Trump administration has devastated agency leadership and independence, firing Shogan, forcing out the deputy archivist, the inspector general, and other agency employees, and putting Rubio atop the agency, while installing as NARA’s day-to-day leader Byron, the head of the most partisan presidential foundation in the system.

Another is that few now seriously believe the president will nominate anyone who meets the statutory requirements for the position, nor one who would reassert the independence of the agency and the position, and honorably uphold the law rather than fulfill the president’s desires.

Anthony Clark is a former speechwriter and legislative director in the U.S. House of Representatives. In the 111th Congress (2009–11), he was the professional staff member responsible for oversight of NARA, the Freedom of Information Act, and the Presidential and Federal Records Acts for the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. A new, expanded edition of his 2015 book on the history and politics of NARA and the presidential libraries will be published later this year by Informative.Ink.

Great Job Anthony Clark & the Team @ The Bulwark Source link for sharing this story.