Lawsuit Says Union-Busting Trump Order Is ‘Unconstitutional’ Attack on Working Class | Common Dreams

April 4, 2025

Sean Combs indicted on additional sex trafficking charges

April 4, 2025In his dispatch from CinemaCon this week, Richard Rushfield highlighted something said by Cinema United head Michael O’Leary that’s been on my mind a lot recently. Here’s Richard:

Cinema United boss Michael O’Leary kicked things off with a forceful “State of the Industry” address, and one statistic in his speech really captured my attention:

Recent data from NRG shows that audience awareness of new movies has been dropping, with a 38 percent decline in movies that reached an awareness level over 50 percent by opening weekend.

There are a lot of ways to measure the falloff we’ve seen, but I think this gets to the heart of the problem: film’s retreat from its central place in the culture and imagination. From this issue, all the other ones flow.

We actually discussed just this fact on Across the Movie Aisle the other day, though we highlighted “unaided awareness” in particular. (“Awareness” is the number of regular moviegoers who are familiar with a film when given a list of upcoming movies; “unaided awareness” is the number of people who can name a specific upcoming movie unprompted.) With both stats, the point is the same: people simply aren’t aware of what’s in theaters, and if they aren’t aware of what’s in theaters they have no way of knowing what there is to see.

Let’s state a premise: Before the pandemic, moviegoing benefited from a virtuous cycle in which people would go to the movies, see trailers for other movies they wanted to see, and then go to more movies because of those trailers. The pandemic, the strikes slowing the flow of product, and the rise of streaming all contributed to help break this cycle: People didn’t go to the movies for a year and a half, and then when they came back release dates kept getting shifted around, and then the strikes strangled the product pipeline further, and then streamers filled the gap for audiences who suddenly didn’t have to wait so long for movies to play on their awesome home theater systems.

We can weight each of these factors differently, but the end result is the same: People stopped going to the movies, so they stopped seeing trailers. (As I’ve written, they also started going to theaters with assigned seating and a seemingly endless number of trailers/ads, which led to audiences showing up after the announced showtime, decreasing the percentage of trailers watched.) Trailers delivered to a captive audience in a movie theater are the best way to create awareness. The virtuous cycle has been replaced by a vicious one: Audiences don’t know about upcoming releases, so they see fewer new movies and are exposed to fewer new trailers, further decreasing awareness.

I do not have great ideas as to how to arrest this spiral. The studio-owned streamers could do a better job of educating people about forthcoming releases; Disney+ is actually pretty effective at this, if my kids are representative. The studios could, obviously, be spending lots of money advertising in newsletters and podcasts that cater to general audiences (hint hint) rather than pure industry trades, though “throwing money at the problem” is a solution with diminishing returns. I’m honestly kind of stumped. There may not be a good solution. If you’ve got a suggestion, leave it in the comments.

On this week’s Bulwark Goes to Hollywood, I talked to Ray Mendoza, who codirected and cowrote Warfare with Alex Garland. We chatted about that movie, his work on Civil War with Garland, and his efforts to get veterans into the movie business. And you should go see Warfare when it comes out next week; the theatrical experience is going to be key to understanding precisely what the guys portrayed in this movie went through.

As a filthy casual—the sort of guy who plays one or two AAA games a year, often several years after they’ve been released—the thing that has been most striking about the state of video games is how static the price point for the major releases has been. I mean, this is a joke from The Simpsons that first aired nearly 30 years ago:

Seventy dollars was the price point for Mortal Kombat 2 when I was a strapping young lad trying to figure out how to sneak photorealistic decapitations past my parents. You want to know what the price point was when I bought God of War: Ragnarok for the PlayStation 5 two and a half years ago?

Seventy dollars.

That’s a remarkable consistency; I honestly can’t think of anything else like it. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says that a $70 purchase in September 1994 is equivalent to a $150 purchase in February of this year (the latest month for which you can calculate inflation on the site). Yes, yes: the video game companies have introduced subscription services and they’ve created downloadable content and new skins and costumes and weapons, etc. Fine, fine. But you’re still paying nominal 1994 prices for games that last dozens of hours or longer, that have near-cinematic-quality visuals, and that in some cases connect to the internet and allow you to play against people all around the world.

The advances in gaming have been staggering; as I discussed with Matthew Ball, R&D costs have spiraled upwards, with franchise entries that had cost $50 million to make (itself an enormous increase over the costs of, say, Street Fighter II or Super Mario Bros. 3) now costing upwards of $500 million. The new Grand Theft Auto is rumored to have cost something like $2 billion to produce, which is one reason why so many in the industry are hoping it will break the $100 barrier.

All of which brings us to Nintendo’s announcement this week that their new console, the Nintendo Switch 2, will debut at a higher-than-expected price point of $449.99 and the big game available at release, Mario Kart World, will cost $80. (There’s been some confusion over pricing differences in Europe and America for physical vs. digital copies, but pre-orders on the websites of Target and Best Buy indicate an $80 price point for physical releases of major Nintendo titles.) Forbes suggests that the insane tariff regime rolled out by the Trump administration probably had something to do with the price increases—the new console, which is manufactured in China and Vietnam, costs 50 percent more than its predecessor and Nintendo has said it is waiting to take preorders until the dust settles on Trump’s war against consumers—but the simple fact of the matter is that prices for games had to come up somewhat to keep pace with inflation and development costs.

An $80 price point for the physical edition of the new Mario Kart means that Rockstar Games will almost certainly roll GTA VI out for $100 at launch; it’s good for the industry as a whole to nudge the standard price point closer to $80 (which is, again, a steal compared to the inflation-adjusted costs of previous, less-developed games). And look: I understand being annoyed by this. I don’t like paying more for stuff either! But the $60 price point is simply untenable for AAA games.

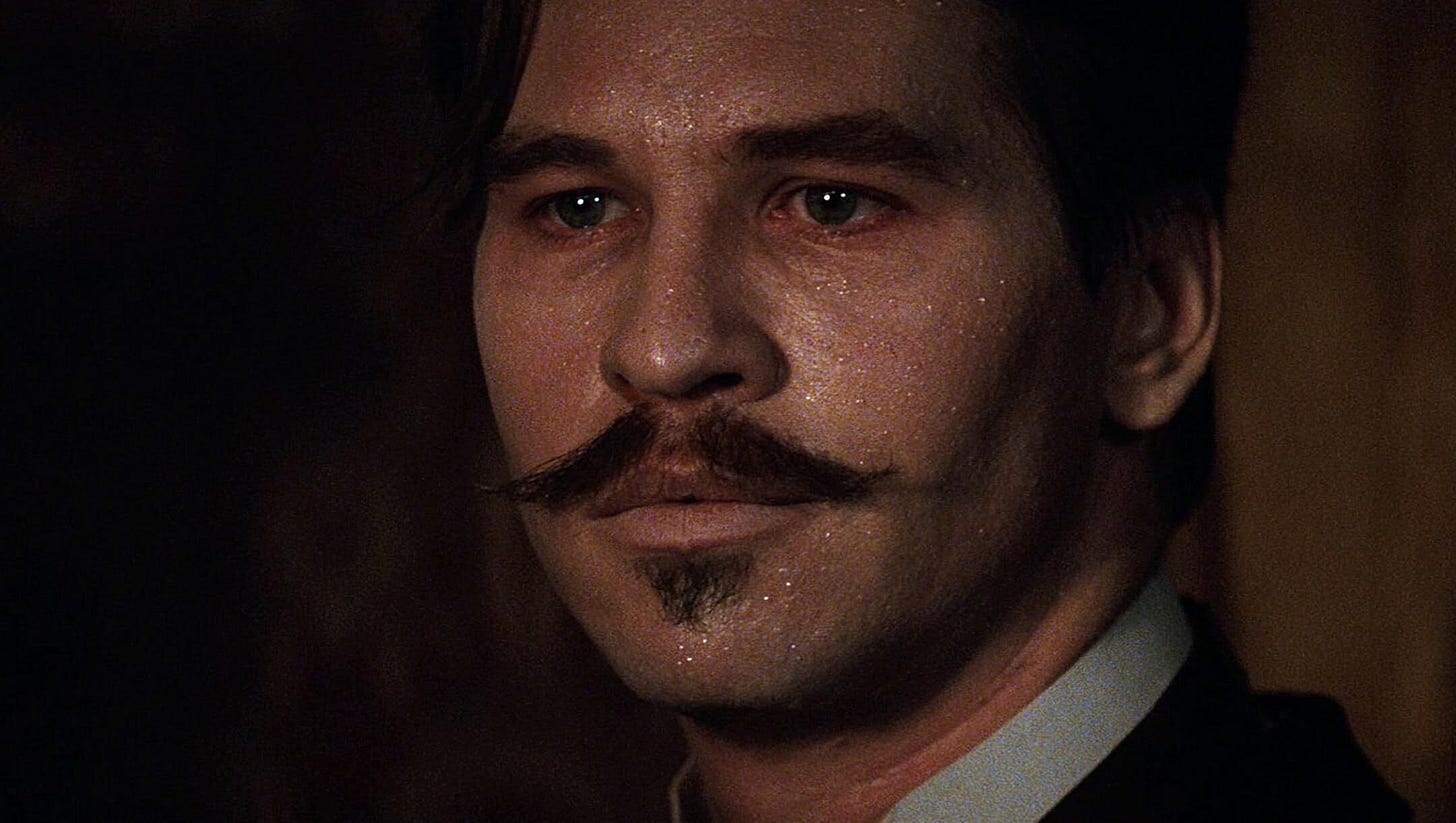

Look, critics are always tempted to highlight a less well-known role when a great actor dies. And Val Kilmer, who died this week, had lots of great roles in underappreciated movies. But let’s be real: his best, most memorable, performance is as Doc Holliday in Tombstone. It’s just a powerhouse performance that outshines a cast full of incredible talents, the sort of role careers are built on.

Great Job Sonny Bunch & the Team @ The Bulwark Source link for sharing this story.