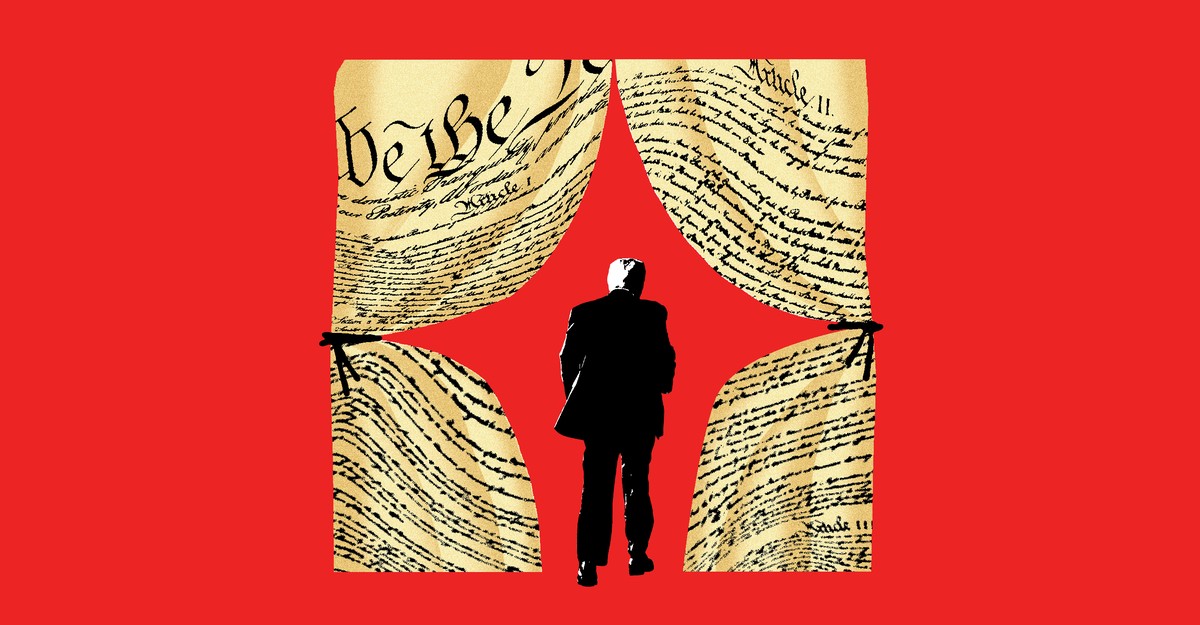

The End of Rule of Law in America

May 14, 2025

The Republican Tax Bill Screws the Working Class

May 14, 2025President Donald Trump is cagey about whether he might try to stay in office after his current term expires. He frequently says that other people want him to do it, and the Trump Organization is selling Trump 2028 hats. In March, he said that he is “not joking” when he refers to a possible third term. More recently, he said that a third term is “something that, to the best of my knowledge, you’re not allowed to do” but then immediately questioned the constitutionality of being prevented from running again. When pressed about how he would serve a third term despite the Constitution’s rule against being elected more than twice, he said, “There are ways of doing it.”

In short, Trump is aware that if he wants to serve a third term, the Constitution—in particular, the Twenty-Second Amendment—presents a problem. But he’s not precluding the possibility. Problems can be solved. Notice how he frames the issue: For the president, the Constitution is not a repository of values that he must respect. When it stands in the way of his interests, it is an obstacle to be overcome.

When Trump says, “There are ways of doing it,” he has in mind work-arounds like the one he calls “the vice-presidential thing.” The idea is something like this: The Twenty-Second Amendment says that “no person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice.” Construed strictly, the prohibition is on being elected, not on holding the office. So if Trump could be president after 2028 without being elected president—say, if he were elected vice president, and then the person elected at the top of his ticket resigned, thus making Trump the president—then he would not be violating the prohibition. After all, he would not be elected “to the office of the President more than twice.”

Whether this work-around would be legally valid is the subject of some controversy among experts in constitutional law. As a strictly textual matter, it makes sense. At the same time, it’s a clear nullification of the purpose of the amendment. No one can know how the Supreme Court would resolve that tension three years from now.

But if the question of how courts would assess such a work-around is murky, Trump’s willingness to promote the idea is enormously illuminating. It reflects his sense that where his interest in power is on the line, the Constitution is something to be evaded.

Usually, a dispute over how to interpret a constitutional provision is, at bottom, a dispute about what that provision is trying to achieve. When a court credits a plaintiff’s argument about the plain text of a constitutional clause over a defendant’s argument about the purpose of that clause, it generally does so because the mismatch between the text and the defendant’s claim about purpose makes the court wonder whether the defendant is describing the clause’s purpose correctly. Maybe the clause is trying to do what you’re saying, the court implicitly says, but if that’s what the clause were trying to do, it would probably be worded differently. And because we aren’t sure about the clause’s purpose, the safest course is to stick to the plain text.

Nothing like that applies in the case of the Twenty-Second Amendment. Everyone understands that the purpose of that provision is to limit the amount of time that any one person can serve as president. That purpose is so clear, and so sensible, that most Americans simply think that the Constitution imposes a two-term limit, rather than a two-election limit. Everyone, surely including Trump, understands that a two-term president who became president again would subvert the point of the Twenty-Second Amendment, whether or not he got into the office by being “elected.” What distinguishes Trump from other two-term presidents is that he appears happy to subvert the amendment’s purpose, if he can figure out a way. He isn’t trying to respect the Constitution; he’s trying to outsmart it.

For some roles within the legal system, trying to outsmart the law is normal behavior. Private tax attorneys try to find clever ways to minimize their clients’ taxes, including by working around the rules when possible. Indeed, the rules are written with the understanding that the people who are governed by them will try to game them in just that way. But presidents are not supposed to treat the Constitution the way a private lawyer treats the tax code—that is, as an adverse force to be defeated. Indeed, the reason the Twenty-Second Amendment can be gamed if read literally is that its drafters did not bother to write it in an airtight way, because they assumed that future presidents would approach the Constitution in good faith—that they would understand, and respect, the point of the Twenty-Second Amendment. Trump must understand the purpose of the amendment, but he feels no obligation to respect it. If he can prevent it from standing in his way, he will.

This approach to the Constitution is typical for Trump. In his first term, when he benefited from foreign diplomats staying at his hotels, public-interest watchdogs contended that Trump was violating the emoluments clause, which prohibits federal officers from accepting “any present, emolument, office, or title, of any kind whatever, from any king, prince, or foreign state.” The clear purpose of the clause is to prevent foreign governments from bribing American officials and, by the same token, to prevent American officials from using their office as a vehicle for personal enrichment. Trump refused to stop the practice, and his administration claimed that he wasn’t violating the Constitution, because the money he was getting wasn’t technically an “emolument” as 18th-century Americans understood that term.

Whether that argument was right about the 18th-century meaning of emolument is controversial. But the logic here is the same: The Trump administration chose to defend an obviously corrupt practice on the ground that it wasn’t technically prohibited. Any previous president would have stayed a hundred miles away from even the appearance of that kind of impropriety, because everyone knows that presidents shouldn’t line their pockets with the money of foreign governments. But in Trump’s view, if there was an available way to argue that the corruption wasn’t prohibited, the fact that it was obviously corruption didn’t matter. Rather than treating the Constitution’s anti-corruption clause (with its language about “any present … of any kind whatever”) as being sufficiently clear about whether federal officials should accept foreign payments, he argued a technical point and continued taking the money.

More than a century ago, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. articulated what legal theorists call the “bad man” theory of law. The bad man, Holmes wrote, does not want to know what his obligations are. He wants to know only what will happen if he engages in a given course of action. If an action causes no adverse consequences to him—if he can get away with it—then the law provides no reason not to do it, even if someone with a different sense of law would regard that action as unlawful.

President Trump’s attitude toward the Twenty-Second Amendment is a classic case of Holmes’s bad-man perspective. Indeed, the bad-man construct captures Trump’s attitude toward law in general. Rather than regarding law as the repository of values that officials should try to realize, the president regards it as a set of obstacles to be worked around as he pursues his interests. If his goals conflict with the project of the law—say, because the law embodies the idea that presidents should not use their office to profiteer, or that nobody should occupy the White House for long enough to risk the system’s sliding into personalist strongman authoritarianism—he will disregard the project of the law and pursue his own goals, as long as he can get away with it.

#Outsmarting #Constitution

Thanks to the Team @ The Atlantic Source link & Great Job Richard Primus