The Missing Branch

May 6, 2025

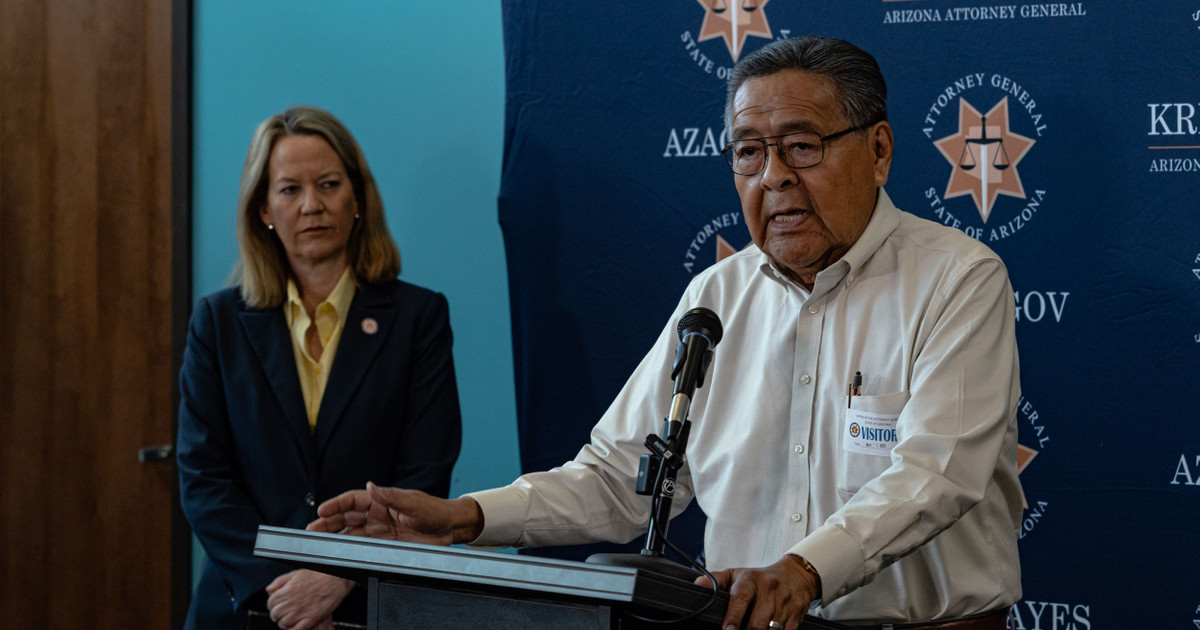

Arizona Has Recovered Just 5% of Taxpayer Dollars Lost in a $2.5 Billion Medicaid Fraud Scheme

May 6, 2025I should note that my reading of Hess’s book is unavoidably colored by my own history. Her pregnancy, and the birth of her son in September 2020, trails my own family’s experience by only a little over six months, but the pandemic makes our experiences radically divergent. I was pregnant in the before times: My husband came to my appointments with me, I did prenatal yoga in a room of 30 other women, and I took birthing classes in the cozy living room of a local doula, whose notions of natural birth I might have avoided if I encountered them online, but to which, in person, I could listen with discernment, hearing a real person’s curiosity, humor, and experience. We never finished the course, as our son was born three and a half weeks early, but we took him to the birthing class to do a live newborn show-and-tell. Had he arrived on his due date of March 22, in the most restrictive week of New York City’s lockdown, I’d have labored entirely alone. As it was, across town from where Hess would give birth that fall, I sat in a crowded waiting room, reading news of Italy’s Covid outbreak on my phone, then spent two days and nights in a shared hospital room, separated only by a curtain from another new mother. The only people who wore masks and gloves were the nurses, whipping them on and off with deft unthinking speed. A couple weeks later, this busy, human normality fell away. As I sat up nights, feeding my son, sirens screamed past the window.

Like Hess, I felt acutely how the eerie isolation of the early pandemic sharpened the solitude of caring for a newborn, and I identified with her yearning for some communal relief. Wouldn’t the “inefficient, depressing, and dull” burden of caregiving, she writes, be lightened by being shared? Turns out there’s a meme for that: a millennial mother asking with naïve optimism, “So, when does the village show up?” The joke’s on her, a woman who has turned her back on the wisdom of previous generations, moved hundreds of miles away from her family, and is now disappointed to discover that a community isn’t available to order online. Seeking it there, among the disembodied scammers, scolds, and cranks, can leave parents feeling even more alone than before. As one scholar Hess talks to puts it, “There’s an emptiness to online communities too—a lack of accountability.” Nobody on a Reddit forum has to look you in the face if their advice makes you sick, and they can’t reach through the screen to stop the baby screaming.

These spaces offer some comforts, to be sure, especially when they are knit together by shared experiences or demographics. The users of the thousand-dollar Snoo “smart bassinet,” at ease in their class privilege, are comfortable “whining and preening” in a private kaffeeklatsch of peers, where no one will be called out for said privilege. Among the followers of the parenting community Big Little Feelings, which started on Instagram in March 2020, the reassurance of community derives from generational identity: millennials, convinced that being kind to their children constitutes a revolution. (After George Floyd’s murder, the account’s response was an earnest suggestion, “punctuated by sparkle emojis,” that firm, loving boundaries could make racism a no-no for a whole generation.) Yet when Hess turns in curiosity to a 1948 copy of Dr. Spock’s parenting guide, looking for evidence of the monstrous parenting mistakes of previous generations, she encounters instead the advice to become a “friendly leader”—which I know from my own motherhood internet is almost exactly the signature phrase of another pandemic-era parenting guru, Dr. Becky.

#Digital #Pregnancy

Thanks to the Team @ The New Republic Source link & Great Job Joanna Scutts