Pro-Palestinian Activists Gave Trump a Boost. They Have No Regrets.

May 4, 2025

Trump’s Sunday Night Brain Dump Will Leave Your Jaw on the Floor

May 4, 2025A new documentary follows a criminalized midwife, the Mennonite women who rallied behind her, and the political battle to legalize life-saving care.

As long as women have been giving birth, people have assisted mothers and newborns up to and through childbirth—making midwifery one of the world’s oldest occupations. The International Day of the Midwife, observed each year on May 5, aims to honor the profession and promote awareness of its vital role in healthcare.

Today, the presence of a midwife greatly increases birth outcomes for both baby and mother.

- Pregnant women with midwives report higher satisfaction and are significantly less likely to have labor induced, undergo cesarean sections, or require interventions like forceps or episiotomy.

- Studies also show midwives’ continuous, individualized care leads to lower rates of maternal and newborn deaths, postpartum hemorrhage, birth asphyxia, preterm births, as well as better immediate health for the newborn.

- Globally, access to midwifery care could prevent over 60 percent of all maternal and newborn deaths and stillbirths—amounting to 4.3 million lives saved each year by 2035—according to the World Health Organization.

- In the U.S., the opportunity to save lives is even greater: The country has the highest rate of maternal deaths of any high-income nation, and Black women are three to 12 times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Better access to midwifery care could potentially reduce maternal deaths by 80 percent, according to journalist and activist Elaine Welteroth, founder of BirthFund, a nonprofit that advocates for better access to midwifery care, especially for Black women.

Throughout history, midwifery regulation was often used as a tool to restrict or eliminate who was allowed to assist with pregnancy and childbirth, where, and how much it would cost.

Today in the U.S, there are several different classifications of midwife, but they generally fall into two buckets:

- A certified nurse midwife (CNM) must be a registered nurse who completed graduate level or beyond. She provides full-spectrum gynecological care, is frequently covered by insurance, and often practices in a hospital and other official medical settings.

- A certified professional midwife (CPM) does not require a nursing degree, meaning a lower barrier to entry. A CPM’s training emphasizes apprenticeship and out-of-hospital births.

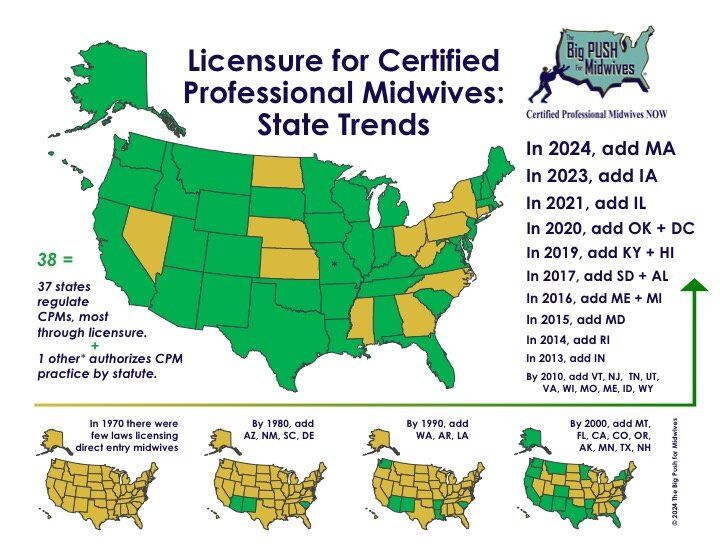

Midwifery laws vary state by state, and are frequently debated and updated: In the last decade, multiple states have enacted legislation to allow more leeway for direct-entry midwives and CPMs to enter the profession.

Midwives looking to practice must stay up to date on the current legal status in their state. Today, 12 states—including blue states with reproductive health protections enshrined in law—do not legally recognize CPMs. (These states are Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio and Pennsylvania.)

But the demand for midwives is great, especially in maternal healthcare deserts, or counties with limited or no access to maternity care services, including obstetric care, birthing hospitals and birth centers. In the U.S., over 35 percent of counties are considered maternity care deserts, affecting over 2.3 million women of reproductive age each year.

One such desert, in one such state—Yates County, N.Y.—is the setting for a documentary that debuted this year at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Film Festival in Austin, Texas: Arrest the Midwife.

Elaine Epstein’s film follows Elizabeth Catlin, a beloved CPM in a small town in upstate New York. Here, Mennonites have a significant presence, and it’s common to see these “plain people” in their simple clothes (usually solid, dark colors) riding in horse-drawn buggies. Though not Mennonite herself, Catlin developed a good reputation among this community, whose conservative Christian way of life discourages birth control and encourages at-home births outside of a hospital setting. She’s assisted with hundreds of births, including almost half of all Mennonite births each year.

In October 2018, Catlin transported a laboring woman to a hospital in Canandaigua, and the baby was born but died hours later of sepsis. Despite the family’s indication they did not blame Catlin or wish to see her prosecuted, and despite the birth taking place in a hospital, Catlin was arrested in 2019 and indicted on 95 felony counts, including criminal homicide and unauthorized practice of midwifery.

The Mennonite community does not commonly participate in modern political life or utilize technology. But Catlin’s arrest and inability to practice midwifery went against the wishes of many of the women in her community—leading them to organize a (handwritten) letter-writing campaign, fundraise for Catlin’s legal and professional expenses, and eventually lobby state lawmakers for the legal recognition and licensing pathway for CPMs in New York.

In New York, “we keep changing the laws, and we keep changing the requirements,” said SeQuoia Kemp, a Black feminist community-based birthworker in Syracuse, in the film. “In the beginning, direct-entry midwife was just fine. Then it became, you needed to become a nurse first. Then it became, you have to have a master’s. How many more times are we going to increase the cost of education so that people that look like me or people within their community can’t afford to become midwives?”

(At the height of COVID in 2020, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo temporarily authorized CPMs to practice in the state, in an effort to reduce strain on hospitals. The order expired on June 25, 2021.)

The film doesn’t offer a neat or fairytale ending—because it unfolds in the real world, where lobbyists stall progress and hospitals often prioritize profit over people. The politically awakened Mennonite community wins some battles, but not all. A Community Midwifery Bill that would have allowed certified professional midwives like Catlin to practice legally in New York failed to pass before the state legislative session ended last year. And while Catlin’s sweeping 95-count indictment was ultimately reduced to a single charge through a plea deal, the legal and emotional toll remains, and she is unable to practice midwifery in the state. Today, she is a school bus driver.

Still, director Elaine Epstein hopes viewers take away something powerful: that meaningful change is often slow, imperfect and comes from unexpected places. “We’re in a time where things are pretty bad and it’s easy to want to bury our heads,” she said. “But we have so much to learn from the Mennonites.”

In a moment of widespread rights backsliding, their quietly determined activism offers a clear lesson: If they can fight, so can we.

Arrest the Midwife is available for streaming on:

Great Job Roxanne Szal & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.