ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Remembering Michael Hurley: Folk Legend Performs in Democracy Now! Studio in 2020

April 4, 2025

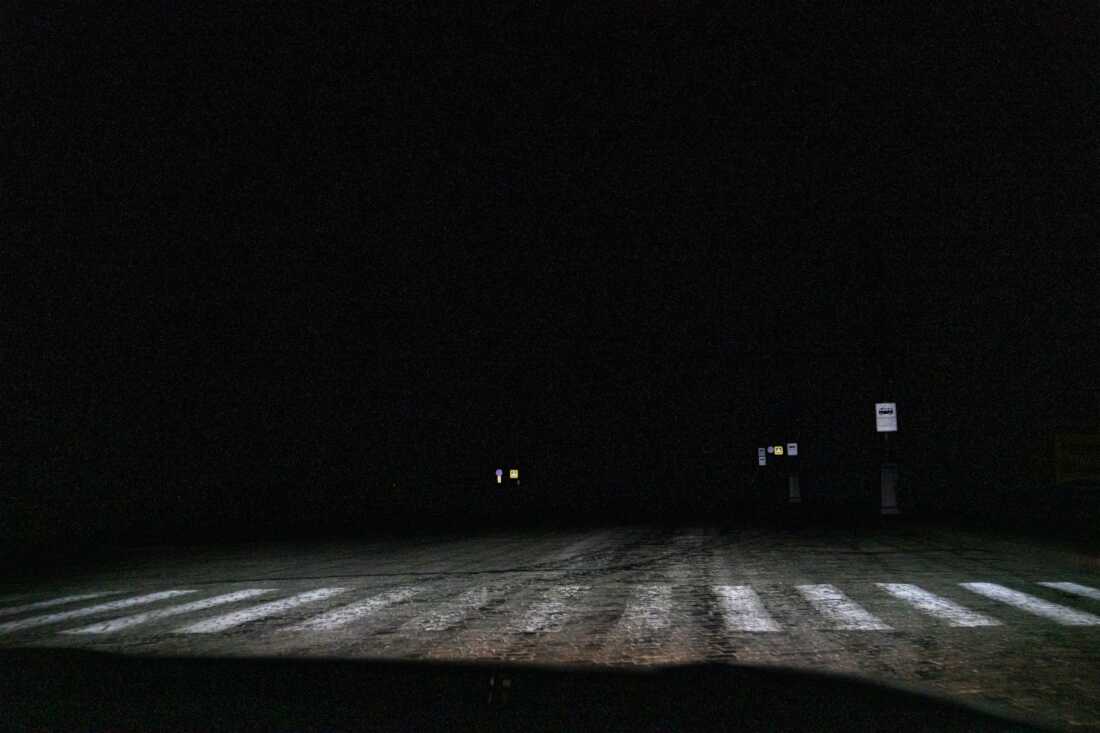

Ukrainians face fears during the country’s darkest nights

April 5, 2025A few weeks ago, my colleague Doris Burke sent me a story from The New York Times that gave us both deja vu.

The piece reported that Starlink, the satellite internet provider operated by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, had, in the words of Trump administration officials, “donated” internet service to improve wireless connectivity and cell reception at the White House.

The donation puzzled some former officials quoted in the story. But it immediately struck us as the potential Trump-era iteration of a tried-and-true business maneuver we’d spent months reporting on last year. In that investigation, we focused on deals between Microsoft and the Biden administration. At the heart of the arrangements was something that most consumers intuitively understand: “Free” offers usually have a catch.

Microsoft began offering the federal government “free” cybersecurity upgrades and consulting services in 2021, after President Joe Biden pressed tech companies to help bolster the nation’s cyber defenses. Our investigation revealed that the ostensibly altruistic White House Offer, as it was known inside Microsoft, belied a more complex, profit-driven agenda. The company knew the proverbial catch was that, once the free trial period ended, federal customers who had accepted the offer and installed the upgrades would effectively be locked into keeping them because switching to a competitor at that point would be costly and cumbersome.

Former Microsoft employees told me the company’s offer was akin to a drug dealer hooking users with free samples. “If we give you the crack, and you take the crack, you’ll enjoy the crack,” one said. “And then when it comes time for us to take the crack away, your end users will say, ‘Don’t take it away from me.’ And you’ll be forced to pay me.”

What Microsoft predicted internally did indeed come to pass. When the free trials ended, vast swaths of the federal government kept the upgrades and began paying the higher subscription fees, unlocking billions in future sales for the company.

Microsoft has said all agreements with the government were “pursued ethically and in full compliance with federal laws and regulations” and that its only goal during this period was “to enhance the security posture of federal agencies who were continuously being targeted by sophisticated nation-state threat actors.”

But experts on government contracting told me the company’s maneuvers were legally tenuous. They circumvented the competitive bidding process that is a bedrock of government procurement, shutting rivals out of competition for lucrative federal business and, by extension, stifling innovation in the industry.

After reading the Times story about Starlink’s donation to the White House, I checked back in with those experts.

“It doesn’t matter if it was Microsoft last year or Starlink today or another company tomorrow,” said Jessica Tillipman, associate dean for government procurement law studies at George Washington University Law School. “Anytime you’re doing this, it’s a back door around the competition processes that ensure we have the best goods and services from the best vendors.”

Typically, in a competitive bidding process, the government solicits proposals from vendors for the goods and services it wants to buy. Those vendors then submit their proposals to the government, which theoretically chooses the best option in terms of quality and cost. Giveaways circumvent that entire process.

Yet, to hear Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick tell it, the Trump administration wants to not only normalize such donations but encourage them across Washington.

Last month, during an appearance on the Silicon Valley podcast “All-In,” he floated his concept of a “gratis” vendor who “gives product to the government.” In the episode, released just a few days after The New York Times published its Starlink story, Lutnick said such a donor would not “have to go through the whole process of becoming a proper vendor because you’re giving it to us.” Later, he added: “You don’t have to sign the conflict form and all this stuff because you’re not working for the government. You’re just giving stuff to the government. You are literally giving of yourself. You’re not looking for anything. You’re not taking any money.”

Since President Donald Trump took office in January, Musk, who is classified as an unpaid “special government employee,” has made a show of providing his services to the president and products from his companies to the government “at no cost to the taxpayer.” The White House donation was just the latest move. In February, he directed his company SpaceX to ship 4,000 terminals, at no cost, to the Federal Aviation Administration for installation of its Starlink satellite internet service.

During our Microsoft investigation, salespeople told me that within the company the explicit “end game” was converting government users to paid upgraded subscriptions after the free trial and ultimately gaining market share for Azure, its cloud platform. It’s unclear what the end game is for Musk and Starlink. Neither responded to emailed questions.

Federal law has long attempted to restrict donations to the government, in large part to maintain oversight on spending.

At least as far back as the 19th century, executive branch personnel were entering into contracts without seeking the necessary funding from Congress, which was supposed to have the power of the purse. Lawmakers didn’t want taxpayers to be on the hook for spending that Congress hadn’t appropriated, so they passed the Antideficiency Act, a version of which remains in effect today. One portion restricted “voluntary services” to guard against a supposed volunteer later demanding government payment.

But in 1947, the General Accounting Office (now called the Government Accountability Office), which offers opinions on fiscal laws, made an exemption: Providing what became known as “gratuitous services” would be allowed as long as the parties agree “in writing and in advance” that the donor waives payment.

Microsoft used that exemption to transfer the consulting services it valued at $150 million to its government customers, entering into so-called gratuitous services agreements. To give away the actual cybersecurity products, the company provided existing federal customers with a “100% discount” for up to a year.

It is unclear whether gratuitous services agreements were in place for Musk’s giveaways. The White House and the FAA did not respond to written questions. Neither did SpaceX. An official told The New York Times last month that a lawyer overseeing ethics issues in the White House Counsel’s Office had vetted the Starlink donation to the White House.

For the experts I consulted, the written agreements might help companies comply with the letter of the law, but certainly not with the spirit of it. “Just because something is technically legal does not make it right,” said Eve Lyon, an attorney who worked for four decades as a procurement specialist in the federal government.

The consequences of accepting a giveaway, no matter how it’s transferred, can be far reaching, Lyon said, and government officials “might not grasp the perniciousness at the outset.”

Tillipman agreed, saying the risk for ballooning obligations is particularly pronounced when it comes to technology and IT. Users become reliant on one provider, leading to “vendor lock-in,” she said. It’s too soon to tell what will come of Starlink’s donations, but Microsoft’s White House Offer provides a preview of what’s possible. In line with its goal at the outset, the world’s biggest software company continues to expand its footprint across the federal government while sidestepping competition.

A source from last year’s Microsoft investigation recently called to catch up. He told me that, with the government locked into Microsoft, rivals continue to be shut out of federal contracting opportunities. When I asked for an example, he shared a 2024 document from the Defense Information Systems Agency, or DISA, which handles IT for the Department of Defense. The document described an “exception to fair opportunity” in the procurement of a variety of new IT services, saying the $5.2 million order “will be issued directly to Microsoft Corporation.”

The justification? Switching from Microsoft to another provider “would result in additional time, effort, costs, and performance impacts.” DISA did not respond to emailed questions.

Doris Burke contributed research.

Great Job by Renee Dudley & the Team @ ProPublica Source link for sharing this story.