The Breakup Edition: Elon x Trump

June 6, 2025

We Should Immediately Nationalize SpaceX and Starlink

June 6, 2025On this week’s episode of The Bulwark Goes to Hollywood, I interviewed New York magazine’s Lila Shapiro about her big feature piece on the extent to which Hollywood is already (quietly) using generative AI in movies. I hope you read her piece and listen to the episode; they’re pretty eye-opening for anyone who has kept tabs on AI creep in the entertainment industry.

I want to briefly highlight one passage in particular real quick, because it’s the sort of thing I find almost viscerally repulsive yet have trouble articulating why. Shapiro is talking here to Cristóbal Valenzuela, cofounder of generative AI company Runway:

In 2023, a group of artists sued Runway and several other generative-AI companies. In response to that suit (which is ongoing) and dozens of similar cases, the companies have largely argued that training their models on copyrighted material qualifies as fair use so long as the models do not reproduce identifiable elements of the original work. In our conversations, Valenzuela likened individual artworks or images to “sand on a beach” — too small and numerous to meaningfully influence the result. When I brought up the example of someone prompting a model to generate a video “in the style of Wes Anderson,” he said the ethical problem rested on the Wes Anderson enthusiast, not on Runway. “You can still do that without AI systems — shoot a film, color-grade it in the style of Wes Anderson, and promote it that way,” he said. “But the person who’ll get in trouble won’t be the camera or the editing software or the computer. It’ll be you.”

Again, I have difficulty articulating my disgust at this response, at least in part because it seems transparently obvious that there’s an enormous difference between a human training to make a film look a certain way and a computer producing a facsimile of the same thing. I also just object to the idea that someone would “get in trouble” for producing a shot that mimics something in a Wes Anderson movie: homage is not theft; reducing art to digital slurry and reshaping it to mimic the original might well be.

But my real concern remains the dead-ending of style and thought that a phrase like “make it Wes Anderson” entails. The very activity of generating the video is in and of itself the sort of thing that destroys critical thinking: Do you even know what “make it Wes Anderson” means? Do you understand the use of symmetry and color, or how the camera movements work, or what the costume design entails? “Make it Wes Anderson” feels like a form of begging the question, a restatement of the premise without an understanding or interrogation of the underlying assumptions.

And then there’s stylistic stagnation. Wes Anderson wasn’t “Wes Anderson” until some years into his career. Yes, some of the tics were there, but Bottle Rocket also has traces of Martin Scorsese (indeed, the great director himself penned an essay on Anderson for Esquire, highlighting the young auteur’s use of a Rolling Stones song to convey an emotional truth) and the looseness of the French New Wave’s Jean Luc-Godard or Francois Truffaut. What we would describe as “Wes Anderson” creeps into The Royal Tenenbaums (his first masterpiece) and begins to dominate with The Life Aquatic. If Anderson had just said “Make it Godard or Truffaut,” well, where would we be?

I dunno, maybe I’m getting too worked up and the whole “make it Wes Anderson” thing will never be used by a real artist or a real executive or a real studio to make a real movie; maybe it’s just a parlor trick, slop for the social media rubes who clap like a seal when someone types “Make the characters from The Big Lebowski babies.” Regardless, I find it anti-art at best, grotesque and post-human at worst. It may be inevitable. That doesn’t make it desirable.

On Across the Movie Aisle’s bonus episode this week, we talked about some of our favorite Disney animated movies; I snuck in a series of plugs for Don Bluth movies. I’m cheeky like that.

‘The Phoenician Scheme’ Review

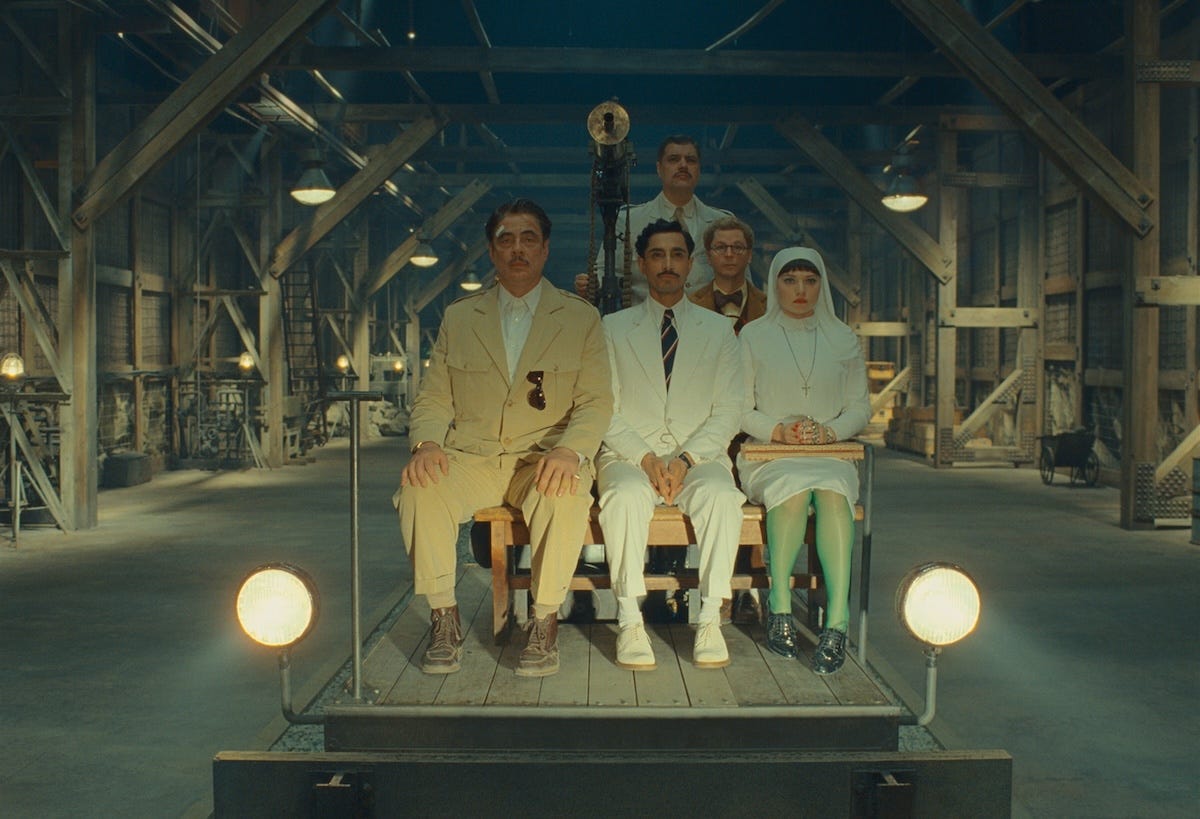

Speaking of Wes Anderson, he has a new one out in theaters. (Fun fact: if you stick through the credits, as I did, there’s a big disclaimer at the end stating in no uncertain terms that this film is not to be used to train AI programs. Not that such warnings mean much of anything to the technologists, but it’s worth a shot.) The Phoenician Scheme is, of course, in the Wes Anderson style, and those who do not care for the Wes Anderson style will likely find this off-putting. But the artifice at the heart of the endeavor only heightens what is a deeply compelling, deeply human examination of what it means to be a family and what it means to do good.

In the opening moments, Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro) finds himself in the midst of yet another plane crash, his sixth. “Mr. Five Percent,” as he is known, is a notorious black-market figure: gun runner, fixer, man of no nation, and, apparently, a pretty good pilot in case of emergency. He walks away, but decides to name an heir—Liesl (Mia Threapleton), his novitiate daughter—to ensure that the greatest plan of his life, the titular scheme, can be completed if he dies.

That scheme? A convoluted tripartite deal involving trains and dams, slaves and starvation, all of which could come crashing down if something as simple as the price of bolts increases. Which it does, which causes Zsa-zsa to take Liesl and executive secretary/bug tutor (don’t worry about it) Bjorn (Michael Cera) on a whirlwind tour of the war-torn Middle Eastern region on an emergency trip to secure gap funding needed to close the deal.

The specifics of these plot points don’t matter all that much; the specifics of every individual sequence, however, are of tremendous importance. And this, of course, is the heart of the Anderson style: It’s not the color palettes or the symmetrical framing or the horizontal dolly moves as if sliding across a stage; rather, it’s about the idiosyncrasies, the weird little touches, the books about, say, semi-pornographic medieval art that Korda flies with for some reason, the box of hand grenades handed out like party favors by Korda to his business partners.

This extends to the actors, as well; as Anderson’s camera work and set design have gotten more mannered (fussier, some would say), so too have the performances by the actors. Though, again, in ways one might not entirely expect: I certainly did not see Jeffrey Wright becoming the greatest weapon in Anderson’s arsenal, but between his emotion-laden monologues in The French Dispatch and Asteroid City and his rhythmic, almost lyrical, turn here as a navy-oriented New Jersey gunrunner, it really feels like there’s nothing he can’t do in service of Anderson’s vision.

The cast is stacked—it’s the sort of movie where a guy who has two Oscars teams up with a guy who has six Emmys1 for a scene and it’s maybe the fourth-most-memorable sequence in the film—but I’d like to give Michael Cera a special shoutout as Bjorn. Cera is a marvelous actor who has been, I think, hurt a bit by the decline of the studio comedy. He’s just tremendously funny in The Phoenician Scheme, doing masterful accent work and a very specific and tight sort of physical comedy that can be hard to pull off. I’ve always enjoyed seeing him show up in stuff and desperately hope he becomes part of Anderson’s repertory company.

Thematically, The Phoenician Scheme calls to mind The Royal Tenenbaums, insofar as it’s about a rake attempting to discern how to live with and for a family. I don’t think this movie quite hits that mark—it’s much closer in vibes to Asteroid City and Anderson’s recent run of Roald Dahl adaptations for Netflix—but I love what he is wrestling with here, the weightiness and morality of what it means, finally, to do good in the world.

Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston, respectively.

Great Job Sonny Bunch & the Team @ The Bulwark Source link for sharing this story.