‘Life-Threatening Catastrophe’: Trump Gutting of USAID Halts Agent Orange Cleanup Work | Common Dreams

March 17, 2025

Hey Democrats: Maybe Now *Is* the Time to Fight?

March 17, 2025

Eric Blanc’s argument in We Are the Union is that only “worker-to-worker” organizing can create union drives that are big enough and cheap enough to save the labor movement. It’s already happening, we need more of it; listen up, union leaders, Blanc says: you can afford it.

If Blanc goes a bit overboard on his points occasionally, that’s fine; he’s making a case. The book is a compelling case not only for organizing millions more workers into the labor movement but for doing it in a way that could help them build power in their unions and in their workplaces.

Blanc is clear that neither he nor the worker-organizers he writes about have invented the notion that workers should have control of their own organizing drives. He cites examples beginning with the early twentieth-century Wobblies to show that bottom-up, nonbureaucratized unionism is an ancient thread in our movement.

Today’s worker-to-worker unionism, in Blanc’s definition, means that workers train other workers in organizing methods, unlike the usual union practice of leaving that mentoring to staffers. The organizing drive itself is initiated by workers, rather than being chosen by union strategists. And the workers have a decisive say on day-to-day strategy — at least partly because there are just fewer staffers around. Hopefully, that’s also because the union has accepted the wisdom of letting workers lead.

Blanc captures well the exhilaration that comes from organizing together and winning. That’s one of the book’s strengths: it makes the reader say, “I’ll have what she’s having.”

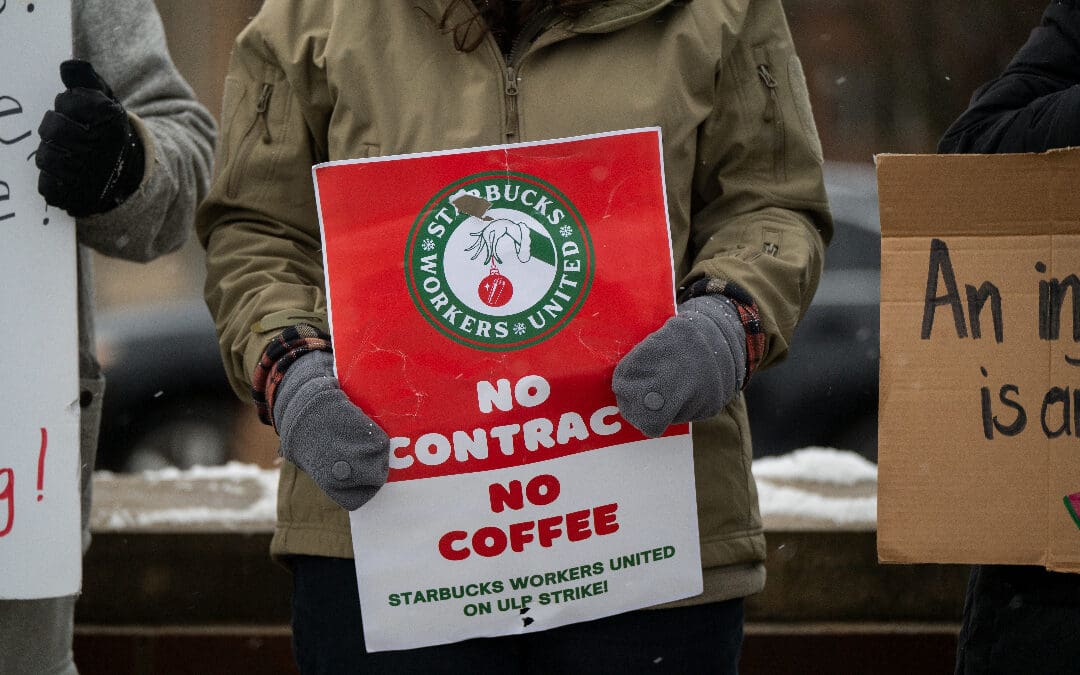

Says one Starbucks worker: “Oh my gosh, it was a beautiful feeling to know that we did it, we showed up for each other and we didn’t allow these corporations to continuously abuse us. It felt like victory, but also just sweet liberation.” Another says, “I’ve been surrounded by so much love that I feel truly invincible.” The book makes the case to the average worker-reader that yes, you can, and you’ll love it.

It’s also aimed at union leaders. A big part of Blanc’s argument is that the usual staff-heavy way of running organizing drives, with a ratio of one staffer per hundred workers, is just too expensive to make a dent in our 90-percent-nonunion workforce. He estimates the cost of bringing new workers into the fold at $3,016 apiece. At that rate, even if leaders threw all of labor’s liquid assets into the fight to unionize, using the traditional staff-heavy model would get us only to 13.2 percent density.

Unlike some other theoreticians of labor revival, Blanc recognizes that in order to convince union leaders who either don’t organize, do it top-down, or do it badly, we will need different union leaders. He celebrates the reform movement in the United Auto Workers (UAW) that won office with a rank-and-file vote, took Big Three workers out on a winning strike, and immediately announced $40 million to organize nonunion auto plants. Similarly, it was a new insurgent president of the NewsGuild (a division of the Communications Workers of America) who made possible the Guild’s well-thought-out worker-to-worker training model and seventy-one first contracts between January 2021 and February 2023.

Blanc contrasts what happened when class-struggle unionists took over in these two unions to the failed exhortations of the New Voices slate that took office in the AFL-CIO in 1995, running on a platform of organizing the unorganized. Union democracy, he says, was dismissed as unimportant, and most unions didn’t even approach the AFL-CIO’s minimum goal of devoting 10 percent of their budgets to new organizing.

“Organizers should be thinking about union reform as much as reformers should be thinking about new organizing,” he concludes.

Besides the frustrated worker on the job and the honcho at the top of the union food chain, We Are the Union is also implicitly addressed to potential salts, workers who take a new job with the intention to organize. Blanc rightly praises their role at Burgerville, a Pacific Northwest chain, and Starbucks. Salts were also important in the Amazon Labor Union victory on Staten Island in 2022.

As exciting as it has been to see Starbucks workers winning election after election across the country — and doing it while training each other on Zoom — I can’t agree that Starbucks is a “fortress at the heart of America’s political economy” or that the hoped-for Starbucks breakthrough (there’s still no contract) is equivalent to the UAW’s winning sit-down strike at General Motors in 1937. It’s an important union struggle; it’s also a coffee shop.

I’m a bigger fan than Blanc is of “targeting,” where union strategists decide where they need to grow their union in order to achieve power against their corporate counterparts. It’s just a fact that some workers have more potential power than others. The new UAW turned to unionizing auto factories, not to the less strategic target of more graduate students, as their lazy predecessors had prioritized.

Blanc says targeting is crucial but also wants to see “seeding,” “across the entire economy, in workplaces of all sizes.” Seeding means casting a wide net: holding open online trainings in organizing; producing social media to generate leads; posting digital ads and training materials for workers to use to self-organize; having union members invite friends and family to trainings; mass texting or phonebanking workers in target companies. In other words, getting the word out there that unions want you and will help you — if you help yourselves.

Seeding sounds great and is relatively cheap. Blanc argues that unions should move toward “supporting any worker looking for organizing help . . . even in small shops.” That’s what the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC) does, and more power to them. Since its founding in 2020, more than five thousand workers have reached out to EWOC. In 2023, EWOC volunteers handed off to unions sixty-five workplace campaigns representing seven thousand workers.

Compare that, though, to the 4,300 workers who joined the UAW at Volkswagen in Tennessee last year, and the nearly 2,500 at Ultium Cells in Ohio and Tennessee, which makes electric vehicle batteries for GM. Let a hundred flowers bloom, but my organizing druthers and dollars would go to the larger workplaces that collectively have the power to take on capital — and thereby inspire other workers.

That’s what happened when the UAW pulled its stand-up strike in 2023: workers across the board were galvanized. Seventy-eight percent of the public, in a Gallup poll, backed the strikers. More important, nonunion autoworkers in the South followed the strike through the UAW’s Facebook Live updates; they searched for and found old organizing websites and asked the union to come to their shops. Similarly, when letter carriers at the US Postal Service voted down a measly contract offer last fall, they said, “If the UAW can do it, why can’t we?”

Blanc cites three factors aiding the recent uptick in worker-to-worker organizing: a proactive and pro-worker National Labor Relations Board, the spread of digital tools, and youth radicalization. We’ve lost the first one, at least for now. But the other two remain.

Blanc is upbeat about the ability of workers to meet and train each other on Zoom, and he cites a number of examples where this has worked. Let’s not forget, though, that the basis of “deep organizing” is mutual trust and respect, which are best achieved through face-to-face conversations and confronting your enemy shoulder to shoulder. Blanc recounts several moving instances of workers’ jubilant celebrations at their winning election vote counts. They were hugging each other’s bodies; they weren’t popping champagne online.

My blood ran cold to read “it costs less to use Spoke or a WhatsApp chat to text updates than to pay a staffer to call members and community supporters.” What about the human connection achieved through those calls? To belabor the obvious, when you text into the ether, you have no way of knowing how your textee took your message, whether it’s coming from a worker or a staffer.

When Unite All Workers for Democracy was campaigning in the UAW in 2022 and 2023, I was one of many volunteers who phoned autoworkers to ask them to organize in their plants. A surprising number picked up the phone, and that human connection was worth a hell of a lot of texts. (Yes, I texted all the ones who didn’t pick up. Some called back. Those who didn’t did not then reach out on their own to ask for leaflets.)

I suppose it’s possible to feel “surrounded by so much love” online, but let’s not get so thrilled with long-distance shortcuts that we forget what builds the ties that last.

I look forward to rereading this book in a face-to-face study group with young socialists who are yearning for a way to be relevant. We’ll learn a lot.

Great Job Jane Slaughter & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.