What to know about the next James Bond movie now that Denis Villeneuve will direct it

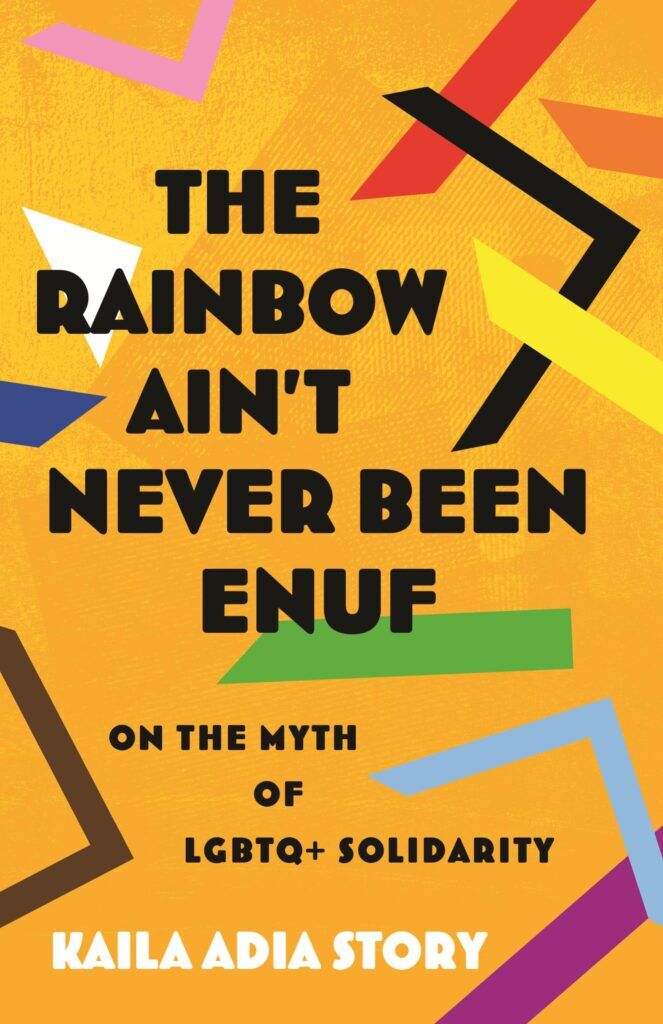

June 26, 2025In her call toward more inclusive rainbows, Kaila Adia Story argues that true queer liberation must center Black feminism and confront racism within LGBTQ+ spaces.

Black Feminist in Public is a series of conversations between creative Black women and Janell Hobson, a Ms. scholar whose work focuses on the intersections of history, popular culture and representations of women of African descent.

The series continues with a conversation this Pride Month with Kaila Adia Story, the Audre Lorde endowed chair and associate professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at the University of Louisville. Dr. Story is co-host of the award-winning podcast Strange Fruit and the author of the recently published The Rainbow Ain’t Never Been Enuf: On the Myth of LGBTQ+ Solidarity (2025).

I recently spoke with Kadia Adia Story for this series about her latest work.

Janell Hobson: What was the inspiration behind writing The Rainbow Ain’t Never Been Enuf?

Story: I wanted to write the book because of the different types of racist microaggressions I would encounter, or overt acts of racism when I entered LGBTQ spaces.

I came out when I was 16, I started sneaking into gay clubs when I was about 17 in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where I lived. I’ve been to these clubs ever since—Chicago, Philly and now Louisville.

When I first got the job here at the University of Louisville, a particular incident happened at a local gay bar up the street from campus in which my group that was made up of minoritized folk—women, femmes, Black gay men—were called the N-slur and the C- and the B-slur. That was the first time anyone had ever used the N-slur against me in any kind of way in all the cities I had lived in, and it was in a gay space by a gay white man.

Hobson: Was it particularly jarring for you that it occurred in a gay space?

Story: My experience through media and through popularized conversations around queer and trans liberation suggested a different perception of what LGBTQ communities represent—that somehow, because of gender and sexual tyranny, they are absolved of any acts of racism and misogyny and that they’re more sophisticated as a community. They’re supposedly above trivial things such as racism, misogyny. But this is completely contradictory to what happens in queer spaces. Hence, the creation of the ball scene, the creation of Black drag networks, the creation of Black Pride and Latinx Pride.

I wrote this book because I didn’t see anyone talking about it in a way in which they related their direct experiences with bias and bigotry to larger social political issues within LGBTQ communities.

Hobson: How does that differ from homophobia and transphobia in Black communities, if you were to compare the two?

Story: I have not encountered vehement acts of homophobia in my experience from Black folk.

I’ve had a pretty privileged experience. My parents and family were very accepting. My wife’s family was accepting. We had five generations of her family at our wedding. My wife came out when she was young as well, and so the encounters that we’ve experienced have been racism and misogyny in queer spaces more so than we’ve experienced homophobia in Black spaces.

There’s been extensive conversations by many Black feminists around Black homophobia, from Barbara Smith to Audre Lorde, and how it’s short-sighted, how it needs to end and how it’s a symptom of white supremacy.

The only time I did encounter Black homophobia and anti-feminist stuff was as a grad student at Temple University when it was Afrocentric and taught that queerness was white and/or European, and that feminism was for white women, and that I should focus on Africana womanism.

Hobson: What to you is the difference between “Africana womanism” and Black feminism?

Story: Black feminist thinkers and scholars are the blueprint for not only Black feminist liberation but queer liberation, trans liberation. Their theory and practice are diligently tied to intersectionality and what human beings experience through multiple forms of identity. And that’s why I start the book off with Pat Parker and her poem about not having to choose identities. Not having to tell one identity to stay home that night. Because that’s when we would really have a revolution, when we can bring our whole selves into a space and be celebrated and welcomed.

Hobson: Is that why you chose to title your book after Ntozake Shange, a recognized Black feminist?

Story: The reason why I call the book The Rainbow Ain’t Never Been Enuf is because I love the way Ntozake Shange uses the rainbow as a metaphor to highlight the differences between intimate partner violence, domestic violence and state violence that Black girls and women experience at the hands of multiple people and communities. I draw a connection to the rainbow that was created by Gilbert Baker in the seventies that’s supposed to highlight all of our gender identities and sexualities. That was the symbol that got me into the gay bookstore when I was 16 and trying to figure out how I was going to explain my lesbian identity to folks. I saw the rainbow as a welcoming symbol for myself, but in actuality, it became a symbol that represented some of the most racialized and gendered harm that I’ve experienced.

Hobson: Your book is subtitled On the Myth of LGBTQ+ Solidarity. What does that mean to you, especially within our current political climate?

Story: I feel as if the media characterizes and portrays LGBTQ communities in a very narrow, siloed way. So, all we care about is being able to marry, being able to serve in the military and that’s it. When queer liberation was thought of historically, because of all the cross-pollination between feminist groups and civil rights groups, you had Sylvia Rivera working with the Young Lords and working with the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. They had different ideas of queer liberation. It meant unionizing sex workers. It meant feeding people. Pride festivals used to be resource fairs that gave key resources to people in LGBTQ communities, but now they’ve turned into this consumerist capitalist marketplace. There’s this idea that LGBTQ communities have one vision for freedom, one vision for liberation, and we’re all solidified together against gender and sexual tyranny. And that’s not the case.

Hobson: What are some examples of this lack of solidarity?

Story: You have groups now like the Log Cabin Gays, you have these Republican conservative gays who basically feel as if the T confuses cisgender folk, and we should get rid of it. We should sever the T, we should get rid of the queer and just be a “normal gay person,” which means being committed to capitalism, patriarchy, racism. Except you just happen to be gay.

Hobson: I appreciate how you revisit LGBTQ history, specifically concerning the Stonewall protests. You highlight the Black LGBTQ+ individuals who were important to this history, especially someone like Stormé DeLarverie, who I believe doesn’t get the same attention as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. How can we bring more attention to her history?

Story: I wanted to highlight Stormé because she showed us that we can protect our own spaces and that we can keep our own selves safe. Stormé noticed that there was constant harassment not only from law enforcement, but just from people walking in Greenwich Village in New York City who would see trans women or people who wore gender transgressive outfits, and they would harass them. Stormé decided that she’ll protect them along with a group of other Black butch lesbians, and they would patrol the streets to keep the girls—what she calls her “baby girls”—safe.

On the one hand, as a feminist, I thought, “Baby girls? These are grown ass women!” But I think Stormé said that to hint at the preciousness of the people in her community, and coming from the experience of anti-Blackness, anti-queerness, anti-woman, she wanted to let the girls know, to let the dolls know, to let the baby girls know, that they’re precious and deserve protection and safety. And I just love that.

I think it’s something that we should go back to honestly. Because I’ll go to Pride festivals, mainstream ones now, and there’s nothing but troops of police. And I get that it’s under the auspices of our own protection, but law enforcement is unnerving to me. It scares me. That’s why I wanted to talk about how LGBTQ communities can respond to the direct need of their communities.

Hobson: What gives you hope in this moment?

Story: What gives me hope is the resistance that I’m seeing. Other Black feminist thinkers and writers, queer and trans thinkers and writers, these new books and writings that are coming out on the multiplicity and complexity of LGBTQ communities. And my students who continue to fight at the legislative level, they’re fighting at the state level, they’re fighting at federal levels. They give me hope.

Every time I get on Threads or Instagram, all I’m seeing in my algorithm are people fighting this tyrannical authoritarianism every single day in all these little ways that they can. That’s what’s giving me hope in this moment. Not that somehow we’re winning, not that things are getting better for Black women or LGBTQ people, but just that those groups are not taking it. They’re standing up for what’s right and what’s true. We keep advocating for a more inclusive future.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘200522034604820’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

Great Job Janell Hobson & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.