National Recording Registry adds Tracy Chapman, Hamilton and the Minecraft game soundtrack

April 9, 2025

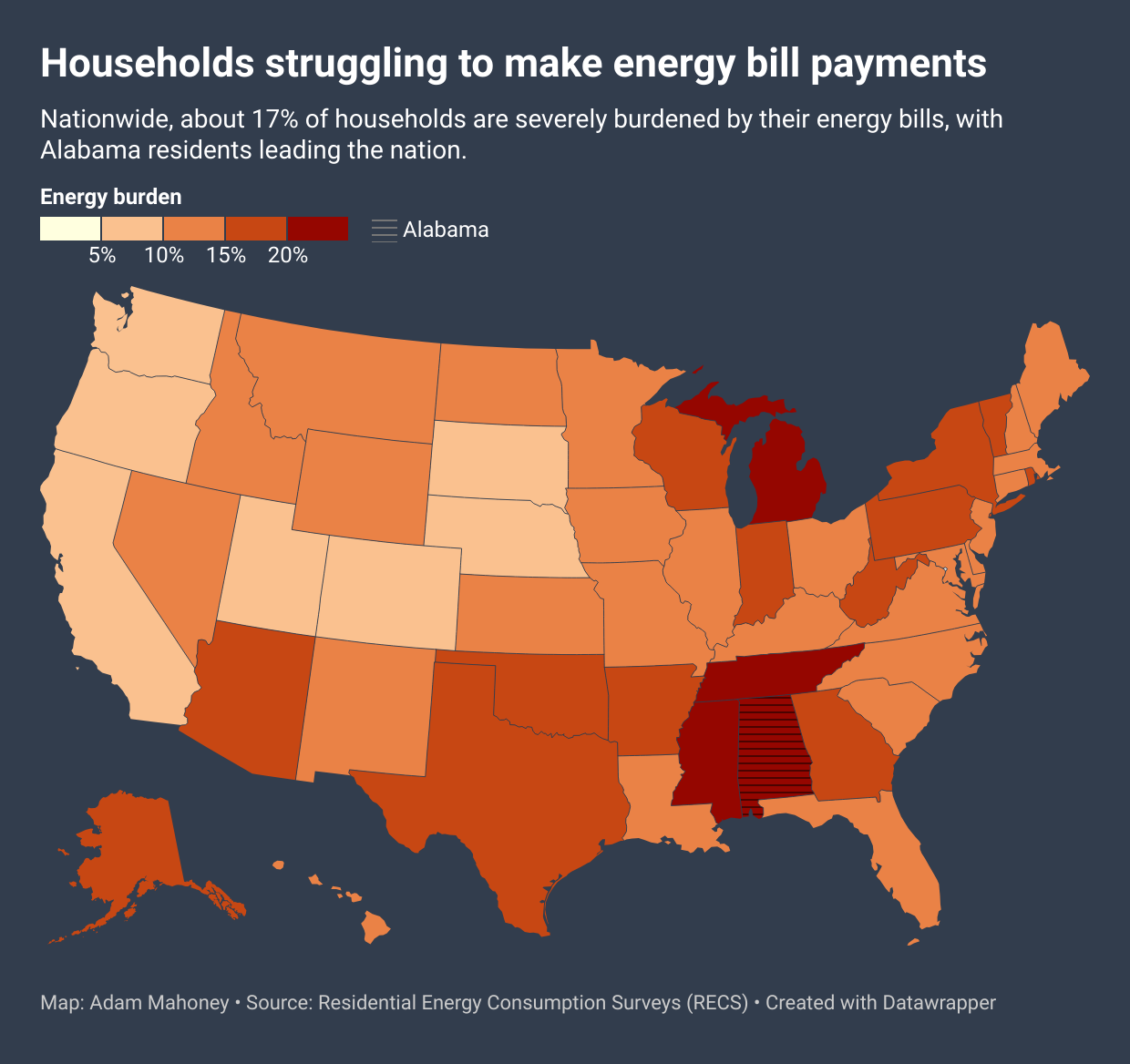

With Southern Utilities Quietly Dismantling DEI Programs, Black Households Pay the Price

April 9, 2025India’s pollution-choked capital city is making a big push for electric vehicles, but much of the adoption is powered by illegal means in the absence of adequate government support.

Late last year, Delhi emerged as the leader in EV adoption in India: 11.5% of its vehicles were electric. This transition has been driven by Delhi’s “multi-segment adoption,” according to a report co-authored by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry, a nongovernmental trade association. Studies show that a majority of the EVs operating in Delhi are e-rickshaws — lightweight three-wheelers used as shared transport for short rides.

Local government policies for EVs, however, have provided scant support for these vehicles, forcing e-rickshaw drivers to improvise with makeshift, illegal, and dangerous solutions. The informal ecosystem arose because Delhi’s current EV policy largely benefits four-wheelers, even though their adoption rate is much lower, mobility experts told Rest of World.

Despite forming a significant portion of Delhi’s EV ecosystem, most e-rickshaws “operate in the informal economy,” said Aravind Unni, an urban policy expert. “Since they largely cater to lower-income groups and last-mile connectivity, their inclusion requires policy measures that address informality, financing challenges, and infrastructural support, which the current policy fails to adequately tackle.”

Nearly 115,000 e-rickshaws were officially registered in Delhi as of December 2022. A more realistic number, including unregistered vehicles, is close to a million, Vighnesh Jha, a trade union leader who works with e-rickshaw drivers, told Rest of World.

Reports estimate that 40% of Delhi’s e-rickshaws may be unauthorized. More than half are charged through power theft, leading to an annual loss of 120 crore rupees (nearly $14 million), officials from electricity distribution companies have claimed. Major utility companies in Delhi did not respond to Rest of World’s requests for comment.

Why wouldn’t we go to the public charging stations if they were for us?

Unauthorized charging stations are usually located within slum communities and informal settlements, or in warehouses, e-rickshaw drivers told Rest of World. Small-scale business owners or landlords operate the stations.

Rest of World visited an unauthorized station nestled within a narrow lane in south Delhi. At least 15 e-rickshaws were parked cheek by jowl. Two wires, loosely connected to each other, snaked out of an electrical outlet, slinking across a damp wall. They supplied electricity to a power strip, connected to a thick cord that charged an e-rickshaw parked over a water-filled pothole.

The person operating this charging station declined an interview request from Rest of World.

Less than 500 metres away, electric cars lined up at a public charging station. The large space was marked by a hoarding that declared “Electric car: On; Pollution: Off” in Hindi. The electrical outlets at such facilities are often incompatible with the adapters used to charge e-rickshaws.

“Why wouldn’t we go to the public charging stations if they were for us?” Mahinder Kumar Vishwakarma, an e-rickshaw driver in his early 50s, told Rest of World. It would just be a matter of paying the government instead of those operating the unauthorized charging stations, he said.

The addition of a socket compatible with e-rickshaws at a public charging station is hardly complicated, Jha said. “The sockets are neither expensive nor logistically challenging. If they wanted to, they would have done it.”

Part of the blame lies with e-rickshaw sellers and manufacturers who are supposed to provide an adapter that can work at public charging stations, Anil Chhikara, Delhi’s former deputy commissioner of transport, told Rest of World. But the government has not done enough to formulate clear, actionable guidelines for the regulation of e-rickshaws either, he said.

In August last year, a 7-year-old boy in northwest Delhi died after he came into contact with a live wire in an unauthorized e-rickshaw charging station. A month later, an e-rickshaw driver lost his life when he was electrocuted as he charged his vehicle. Such incidents occur frequently during the monsoon season, Chhikara said. “Fire accidents, electrocutions … it is risky.”

Accidents can be averted with training, awareness, and dissemination of knowledge, Moushumi Mohanty, head of electric mobility at the Centre for Science and Environment, told Rest of World. With the appropriate safety measures, charging EV batteries at home is more cost-effective and can also ensure a longer shelf life compared to commercial chargers, she said.

The owner of an illegal charging center in Delhi, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he feared repercussions from officials, told Rest of World he charges 100 rupees ($1.16) for a full charge on an e-rickshaw, which can take up to 6–7 hours. This is nearly double the regulated price in Delhi.

The government body that regulates electricity within Delhi has fixed the tariff to charge e-rickshaws at 4.5 rupees (less than 1 cent) per unit. This works out to a total of 50 rupees (6 cents), since about 10 units are needed to fully charge an e-rickshaw, according to one driver’s estimate.

Delhi’s current EV policy, which has been in force since 2020, offers financial subsidies and infrastructural support to hasten EV adoption. For e-rickshaws, this includes a purchase subsidy of 30,000 rupees ($349), and an interest subsidy of 5% on loans for those powered by a government-approved battery.

Many e-rickshaw drivers belong to communities marginalized by class and caste — they are “unaware of their rights and do not benefit” from existing schemes, Unni said. Since many of these vehicles are unregistered, their owners cannot access government support, Chhikara said.

Rajesh, who uses only his first name, bought an e-rickshaw for 1.65 lakh rupees ($1,918) six years ago by taking a loan from a friend. A former factory worker from the eastern state of Bihar, he hoped the relative independence would afford him time to pursue music, he told Rest of World.

Rajesh has since incurred about 70,000 rupees ($814) in fines because he did not renew his e-rickshaw’s fitness certificate, a document issued by regional authorities to certify the vehicle as compliant with safety and emission standards. He earns up to 1,200 rupees ($14) daily.

This gap in policy design shows a disconnect between the government’s EV transition goals and the needs of the majority of its EV users.

Rajesh said he initially could not renew the certificate because he did not have the money to repair the wear and tear on his vehicle from regular use. By the time he had saved enough, the fines had accumulated. He thought it best to evade the process altogether.

The purchase subsidy for e-rickshaws could have helped Rajesh. He visited government and company offices for four years, but to no avail. “They would say the subsidy hasn’t come in yet, or that higher officials are not sending the company any money, or that the company has shut down,” he said.

Five of the six drivers Rest of World spoke to said they purchased their own e-rickshaws and attempted to claim the subsidy. One said he succeeded.

Most of these drivers also bypassed the fitness certificate because they could not afford the lithium-ion batteries that the Delhi government has mandated for e-rickshaws since 2022. They instead opted for the relatively inexpensive recycled lead-acid batteries — which are hazardous and have been banned for use in e-rickshaws.

Last year, Delhi’s civic authorities impounded 1,000 unregistered e-rickshaws, which were to be scrapped if their owners did not apply for registration within seven days.

Such actions are counterintuitive to “creating enabling conditions,” said Unni. “This gap in policy design shows a disconnect between the government’s EV transition goals and the needs of the majority of its EV users.”

Delhi’s current EV policy will soon be replaced by a version that reportedly intends to transition all new vehicles to electric by 2027, set up 13,200 charging stations, and replace conventional auto rickshaws with electric variants.

“I don’t know about EV policies, and cannot comment on them,” Dhole Aom Kashinathrao, a deputy commissioner in Delhi’s transport department whose work assignments include the EV cell, told Rest of World. Neither he nor the office of Pankaj Kumar Singh, Delhi’s transport minister, responded to Rest of World’s emailed requests for comment.

#Illegal #charging #stations #powering #Delhis #erickshaw #revolution

Thanks to the Team @ Rest of World – Source link & Great Job Suprakash Majumdar