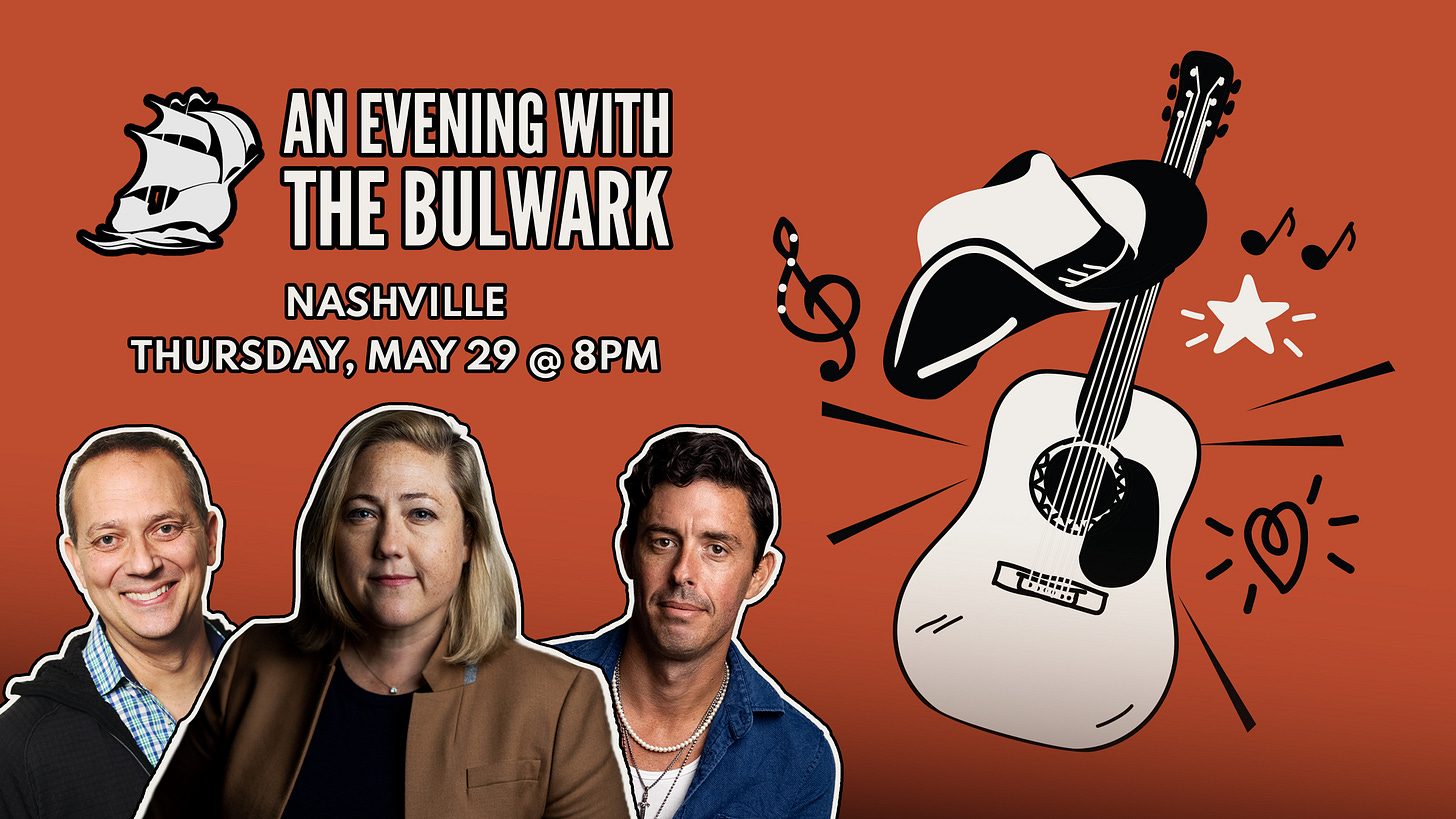

Chicago and Nashville Here We Come

April 23, 2025

Israeli Far-Right Minister Makes Disturbing Comment After GOP Meeting

April 23, 2025

New York City has had only one mayor who belonged to a socialist organization, David Dinkins, but almost no one knew it. His membership in Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) came at a time when the organization had little visibility, and it seemed to have nothing to do with how he conducted himself in office.

Ironically, the mayor who governed like a socialist of sorts — Fiorello La Guardia, who served 1934 to 1946 — was a lifelong Republican. Throughout his career, first in Congress and then as mayor, La Guardia had strong ties with those to his left. In 1924, he even successfully ran for reelection to the House of Representatives on the Socialist Party line, after his own party denied him the nomination because of his support for Progressive Party presidential candidate Robert M. La Follette. (Though LaGuardia asked to be listed in the House as a Progressive, the clerk put him down as a Socialist, leading the only actual Socialist in Congress, Milwaukee’s Victor L. Berger, to drolly declare the New Yorker “my whip.”)

More than his left-leaning alliances or his brief adventure as a nominal Socialist candidate, though, it was what La Guardia did in office that made him a model for what a socialist mayoralty might look like. Just a few months ago, that prospect appeared utterly improbable. But with the extraordinary rise of the candidacy of DSA member Zohran Mamdani, a look back at La Guardia’s time as mayor, and why he was able to accomplish so much, seems in order.

Historian Thomas Kessner titled his still-definitive 1989 biography Fiorello H. La Guardia and the Making of Modern New York. Since its publication, authors (including this one) have used and abused the “Making of Modern” formulation to describe both the trivial and the world historic. But in the case of La Guardia, it rings true. New York City was, in myriad ways, a very different place before and after La Guardia.

Most obvious was its physical transformation. Under La Guardia’s leadership, New York City undertook a massive construction program, unrivaled by anything before or since. The current city highway system is largely the creation of his administration, including the completion of the Triborough Bridge, the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, the Belt Parkway, the Henry Hudson Parkway, and the East River Drive.

More important, in a city then and now made up overwhelmingly of families without cars, La Guardia extended the small, city-owned Independent Subway System into the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens with the construction of what are now the A, B, C, D, E, F, and G lines. He then took over the two large, privately operated subway systems and merged everything to create the modern, publicly owned mass transit system that is so central to life in the city. He also built the first municipal airport, now named after him, just six miles from Times Square.

The La Guardia construction spree extended far beyond transportation infrastructure. With parks commissioner Robert Moses leading the charge, the city built nearly two hundred playgrounds, many in crowded neighborhoods that lacked recreation space. It also built the Central Park and Prospect Park zoos; two new beaches, Jacob Riis and Orchard Beach; and gigantic outdoors swimming pools, like the ones still operating in Astoria, Crotona, McCarren, Betsy Head, and Highbridge Park. New schools popped up all over the city, including the high school I went to, Bayside (which both the current mayor, Eric Adams, and the head of the city council, Adrienne Adams, likewise attended). And in a pioneering public health effort, the La Guardia administration built fifteen neighborhood health centers.

La Guardia also launched the largest, and one of the most successful, public housing programs in the country. In 1934, the city created the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). To lead it, the mayor appointed several longtime housing reformers and a veteran socialist, B. Charney Vladeck. After undertaking a small tenement renovation project on the Lower East Side, First Houses, NYCHA sponsored two large pioneering projects, the Williamsburg Houses (restricted to white families) and the Harlem River Houses (for African Americans). It then rolled out a wave of additional projects, culminating, before World War II halted construction, in the Queensbridge Houses — which, with over 3,100 apartments, was (and still is) the largest housing project in North America.

The La Guardia program in some ways resembled that of the “sewer socialists” of the early twentieth century. The moderate wing of the Socialist Party, sometimes derided by those to its left for its lack of engagement with questions of national or international revolution, pursued incremental improvements in public services for urban immigrant workers and their families. The changes brought about in cities like Milwaukee where the socialists achieved power cumulatively proved transformational in working-class lives, as did the La Guardia reforms.

For a child, what a difference it was between having to play in a dirty lot or dodge cars in the streets and having a playground and swimming pool nearby. For families, leaving a slum tenement for a new public housing apartment, with modern appliances and sanitary conditions, made everyday life utterly different. So, too, did the ability to go just about anywhere in the city for only a nickel on the expanded transit system. And for many families, a local health center meant access, for the first time, to modern medicine. This was not a revolution, but it was in its own way revolutionary.

The La Guardia public works not only brought new comforts and services to working people — they also were a massive employment program during the depths of the worst depression the country had faced. La Guardia saw no contradiction between the need to create jobs quickly and elevating civic standards, offering working people not minimal amenities and services but the best possible. The social critic Lewis Mumford wrote that the Harlem River Houses exemplified “what New York might be if we wanted to make it rival the richer suburbs as a place to live and bring up children.” (Because of changed federal funding rules, later public housing projects did not match its quality.) The high schools built in the La Guardia era were grand edifices with indoor swimming pools, including Bayside (where, bizarrely, at least in my day, the boys took swimming classes in the nude). The campus built for Brooklyn College had the air of a traditional, upscale private college, with a Georgian-style quad.

Buildings, infrastructure, and social services were important, but La Guardia believed ordinary people deserved more. Running for mayor, he declared, “I want justice on the broadest scale. . . . justice that gives to everyone some chance for the beauty and the better things of life.” That meant, among other things, culture and the arts. When during World War II, the city took over the massive Shriners Temple on 55th Street for failure to pay taxes, La Guardia, working closely with several labor unions, established the nonprofit City Center for Music and Drama, which presented low-cost theater, symphonic, ballet, and opera performances. The New York City Opera Company not only offered tickets at a third the price of the Metropolitan Opera; it also, unlike its establishment rival, refused to practice racial discrimination in the singers it presented.

La Guardia used this same approach, of having the city ally with unions (and in this case also progressive health professionals), to establish a nonprofit entity to offer working people quality health care. Anticipating the failure of proposals to establish a national health insurance system, in 1944 La Guardia helped launch the Health Insurance Plan of Greater New York (HIP), an innovative, nonprofit, prepaid, group practice medical system. He guaranteed its initial success by offering to cover half the premium for any city employee who wanted to enroll.

New structures and institutions were only part of La Guardia’s success. Upon taking office, he greatly improved municipal relief efforts, taking responsibility for the plight of the victims of the national economic collapse. (Paltry relief efforts in the early years of the Depression contributed to the collapse of support for the Republicans nationally and the Tammany Hall Democratic machine locally.) La Guardia also aggressively supported organized labor during a moment of explosive union growth. The mayor backed the closed shop and declared he wanted to make New York a “100 percent union city.” To that end, he set up a city board to supervise union recognition elections and mediate disputes and restrained the police department practice of breaking up picket lines and arresting strikers.

For La Guardia himself, perhaps the most important issue was his crusade against Tammany Hall and municipal corruption, the issue on which he focused his first campaign for mayor. Portraying himself as a crime fighter, La Guardia liked nothing more than accompanying police raids on gambling houses and smashing confiscated slot machines. Attacking the patronage system that sustained Tammany, La Guardia strengthened the civil service system, getting rid of biased tests that had been used to keep out Jews, Italians, and African Americans (in the process greatly weakening the Irish hold on municipal employment).

He also pushed through the modernization of the city administrative and governance structure. Most important, a charter reform he initiated replaced the bloated and often corrupt Board of Alderman with a smaller city council, elected using proportional representation. The new system led to a legislative body whose makeup closely mirrored public sentiment, allowing union leaders, socialists, and eventually two communists to be elected. (Precisely for this reason, during the Cold War conservatives managed to eliminate proportional representation, ensuring the Democratic Party’s grip on the council ever since.)

La Guardia certainly had his shortcomings. The purchase of the two private subway systems as part of transit unification was as much a bailout of firms in deep financial difficulty, after decades of failing to upkeep their lines and equipment, as it was a public-serving rationalization. La Guardia refused to sign contracts with the already unionized private-line transit workers when they became municipal employees, reflecting his belief that private-industry-style labor relations, with exclusive recognition, union shops, and formal contracts, were inappropriate in the public sector (a view shared by Franklin D. Roosevelt).

Sometimes, when the political cost seemed too high, La Guardia abandoned his support for First Amendment rights. When a judge blocked the appointment of renowned philosopher Bertrand Russell to a professorship at City College, citing his iconoclastic views on sex, marriage, and religion, the mayor refused to appeal the decision. Further pandering to religious groups, he ordered the Sanitation Department to remove magazines deemed too sexy from newsstands. And though La Guardia’s record on racial equality was better than most contemporary mayors, it was still not much to be admired. He appointed African Americans to significant positions and, after a 1935 riot, invested in public works in Harlem — but he also tolerated segregation in public and public-subsidized housing and failed to act against racism in the police department and other city agencies.

Still, it is remarkable how much good La Guardia achieved. How and why was he able to do so?

Some of it had to do with his history and political skills. La Guardia’s background was uncommon. Usually thought of as a quintessential New Yorker, La Guardia, though born in the city, grew up in the West, in the Dakota Territory and Arizona, on Army bases where his Italian-born father served as a military band leader. Far from a product of urban slums, La Guardia was closer to a rural progressive in his sensibility. At eighteen, he moved to Europe to serve as a clerk in the US consulates in Budapest and Fiume. Only at age twenty-four did he settle down in New York, working as a translator on Ellis Island and then as an immigration and labor lawyer.

If not a typical New Yorker, La Guardia’s background nonetheless served him well when he entered politics. For one thing, he was virtually a balanced ticket unto himself. His mother was a Jew from Trieste, his first wife Catholic, his second Lutheran, while he himself was Episcopalian. He spoke not only Italian, but also German, Hungarian, Croatian, and French. Once, when an opponent’s campaign accused him of antisemitism, La Guardia challenged his rival to debate in Yiddish, a language he had mastered, unlike his Jewish foe.

For another thing, he came to know the plight of poor New Yorkers personally; both his first wife and daughter died of tuberculosis, contracted when the family lived in Greenwich Village, in the days when it was still largely an Italian working-class neighborhood. When in 1916 he won a House seat from Lower Manhattan, his earlier background made him a natural ally of the Western Progressives in Congress, where he opposed immigration restriction, supported labor rights, and called for the nationalization of coal mines. La Guardia’s thirteen years in Congress and two years heading the Board of Aldermen gave him a deep knowledge of how things worked both in Washington and Gotham when he entered City Hall.

La Guardia, as a Republican in a Democratic city, became mayor only because of an unusual set of circumstances. In 1933, the New York City Democratic Party was deeply split between the Tammany Hall machine, which had proved itself both corrupt and incapable of dealing with the challenges created by the Great Depression, and reform-minded liberals allied with FDR. Meanwhile, patrician Republicans, determined to oust Tammany, backed a “Fusion” movement to bring together good government types regardless of party. Running on both the Republican and City Fusion lines, La Guardia put together an unusual coalition of Italian Americans, affluent Republicans, some independent-minded Democrats, and leftists. It only gave him 40 percent of the vote, but that was enough to win, as the Tammany candidate and a reform Democrat split the rest.

The New Deal and the rising labor movement kept La Guardia in power. The New Deal came to New York City not through the Tammany-controlled Democratic Party, which had been at war with Roosevelt since the late 1920s, but through the La Guardia administration. Immediately upon winning office, La Guardia turned to Washington for support and funding, and he got it in spades. New York, with its tradition of urban planning and capable (if controversial) officials like Moses, was exceptionally well-equipped to seize the opportunities created by the New Deal recovery agencies. It was the flood of New Deal money that made possible all the roads, tunnels, subways, parks, public markets, and high schools that transformed New York during the La Guardia era. Prior to the New Deal, cities had very little direct relationship to the federal government. But with the New Deal, even municipalities with far less energetic and progressive mayors than La Guardia were able to upgrade their physical infrastructure, social services, and health and education systems.

La Guardia’s close relationship to the New Deal and the civic transformation he undertook with federal money positioned him for reelection in 1937. But he needed a political vehicle beyond the Republican and City Fusion lines if he was going to beat a Democrat in a two-person race. He helped create one in New York’s American Labor Party (ALP), formed in 1936 to win votes for Roosevelt from socialists, Republicans, and liberals who would never pull a lever for the Democratic Party.

When Roosevelt received some 275,000 votes on the ALP line, the labor leaders and progressive politicians who had created it decided to keep it going. The ALP, with its base among workers, particularly Jews, belonging to unions associated with the burgeoning Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), extended the political life of La Guardia (who, at least measured by votes, was never as popular as his Democratic predecessors and successors). Only because of ALP backing was La Guardia reelected in 1937 and 1941 (in the latter year by a hair’s breadth).

New York City mayors have limited ability to improve the lives of working people. Most important, they have no control over national economic conditions that shape the day-to-day realities of working-class life. They also are subordinate to the state government when it comes to taxation, borrowing, and many aspects of municipal administration. During his eight years as mayor, Bill de Blasio found himself repeatedly undercut and blocked by governor Andrew Cuomo, even when it came to his efforts to protect public health during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Still, there are things a mayor can do with minimal federal or state help. The municipal budget is so huge that new initiatives can be at least partially funded by reallocations, as Zohran Mamdani has proposed for a Department of Community Safety (shifting some money from the police department). Other initiatives cost little or nothing, like keeping down stabilized rents and issuing undocumented immigrants identification cards with discounts attached, as De Blasio did. And not unimportantly, the mayor can set a social and moral tone for the city — the way La Guardia expressed playfulness and solidarity when, during a newspaper strike, he read the comic strips over the radio — and advocate on its behalf in Albany and Washington.

The mayor also has some tools to promote labor organizing, from procurement and contracting rules to the public soap box. Imagine if the mayor walked the picket lines at retail stores and other establishments where workers were trying to unionize, as President Joe Biden did during the 2023 United Auto Workers strike.

Yet there is no disguising that the transformational mayoral regimes in New York occurred when the federal government was in alignment with local efforts and willing to fund them generously. This was true for La Guardia and later true for John Lindsay, who used Great Society money from Washington to improve social services and fund anti-poverty programs. A socialist, or even a progressive, mayor would find it hard going in the current political environment, where the federal government is doing everything it can to undercut urban social programs rather than support them, and the current governor, Kathy Hochul, like her predecessor, Cuomo, likes to stick her nose into city affairs.

La Guardia did not have direct ties to a social movement, except for his Italian American campaign operation, the Ghibonnes, led by his protégé Vito Marcantonio (who would go on to a political career of his own, well to the left of La Guardia). But his advances were possible because of the national and local mobilizations of workers, the unemployed, tenants, and political radicals in response to the Great Depression. Their disruptions pushed national politics to the left and drove the New Deal to launch its huge investments in urban improvements. They also provided the basis for the creation of the ALP, which kept Tammany at bay.

A mayor more directly tied to a radical popular movement would have the ability to unite mass mobilization with administrative and legislative strategy. In that scenario, if external conditions were right, New York once again might experience the kind of progressive transformation it had in the past.

Great Job Joshua B. Freeman & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.