Women made history in space long before the Blue Origin flight

April 14, 2025

Trump-Musk Assault on IRS Could Let Wealthy Evade $30 Million in Taxes—Per Day | Common Dreams

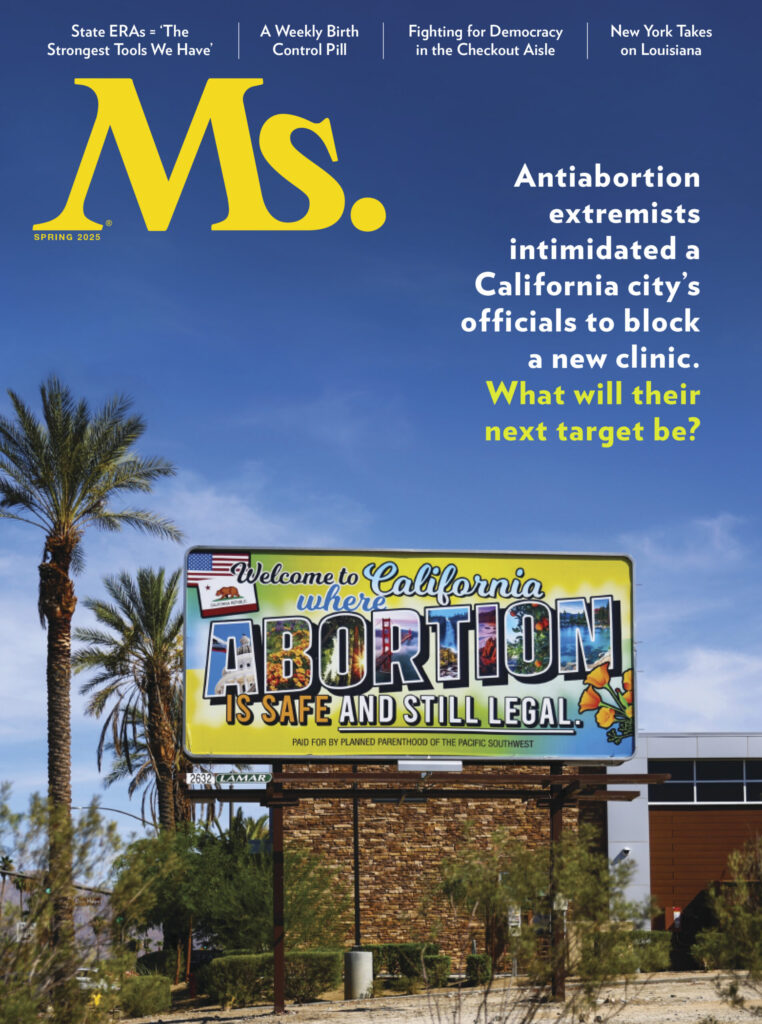

April 14, 2025After antiabortion extremist groups convinced city officials to help prevent the opening of an all-trimester clinic in Beverly Hills, Calif., where will they try next?

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue of Ms. Join the Ms. community today and you’ll get issues delivered straight to your mailbox.

On Jan. 23, in a move as brazen as it was predictable, President Donald Trump pardoned nearly two dozen antiabortion extremists convicted during the Biden administration of violating the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act. Even those who’d also been found guilty of “conspiracy against rights” got a get-out-of-jail-free card. Trump told reporters present that it was “a great honor” to sign the pardon.

The extremists—described as “peaceful pro-life protesters” by a Trump aide at the signing—had violently forced theirway into abortion clinics in four states and Washington, D.C. At one location, the invaders knocked a clinic worker down; at another, a nurse sprained her ankle in the chaos. During the invasion of the Washington Surgi-Clinic, a distraught woman who’d so badly wanted another child that she’d gone to three different doctors hoping, praying, that her current pregnancy could be OK, slumped in agonizing pain onto a hallway floor as her husband frantically tried to reason with the protesters blocking the door to the clinic’s surgical area. The woman managed to inch her way up against a wall, only to have a protester shove her back down to the ground.

By no coincidence, the annual antiabortion March for Life took place in Washington, D.C., the day after Trump issued those pardons. That same day, the Trump administration’s new Justice Department announced that the three pending antiabortion FACE Act cases were being dismissed—effective immediately. Per a department memo:

- No new abortion-related FACE Act prosecutions could be initiated without special authorization.

- Until further notice, the attorney general would consider filing FACE Act charges only if an antiabortion crime involved “significant aggravating factors, such as death, serious bodily harm, or serious property damage.”

At the March for Life, a group was caught on video gleefully chanting through megaphones and amplifiers, “We are clinic invaders, and yours is next!”

Just two weeks later, Kristin Turner—of the extremist groups Progressive Anti-Abortion Uprising (PAAU) and Pro-Life San Francisco—made that threat specific. In a Feb. 11 post on Facebook, she named the next target: the Washington Surgi-Clinic, the very clinic where some of the pardoned protesters had been so pitiless to a woman’s emotional and physical agony.

“We’re shutting it down,” Turner wrote.

How? By using the playbook Turner said they’d developed in 2023, during the process of “successfully prevent[ing] a late-term abortion facility from opening in Beverly Hills, California” (by “late-term,” Turner means “all-term”)—the now terminated DuPont Clinic LA.

A New Kind of Antiabortion Warfare

The prequel to the plot that became #StopDuPont began in June 2022. Three days after the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the California Legislature put a measure on the Nov. 8, 2022, ballot. Prop 1, as it was commonly called, would add “the fundamental right to choose abortion” to the state constitution.

There was no suspense about how the vote would go: Prop 1 would win, and win big. A majority of Californians have supported the right to abortion from the moment it became a political issue, and California law and the state Supreme Court have protected that right for decades.

But the state’s Reproductive Privacy Act was just a statute—a bill passed by the legislature and signed into law by the governor. If one day the political winds changed or some cabal of rogue lawmakers grabbed power, the legislation protecting the right to abortion in California could be overturned too. An amendment to the constitution, on the other hand, would remain untouchable.

During the Prop 1 campaign, Turner was both the executive director of Pro-Life San Francisco (PLSF), which has led harassment campaigns against abortion clinics and reproductive healthcare providers, and the communications director of PAAU, which is based in Washington, D.C.

On Oct. 18, 2022, DuPont Clinic in D.C. posted the following on what was then Twitter:

“DuPont Clinic is thrilled to announce that we are expanding to Los Angeles, California! We plan to open Fall 2023 under the leadership of Dr. Jennefer Russo. The need for all-trimester abortion has never been greater.”

On Nov. 9, the day after California voters approved Prop 1 by a two-thirds margin, Turner posted a motivational video to all PLSF social media accounts:

“Last night we saw a devastating loss … Our next step here at Pro-Life San Francisco is to make Prop 1 irrelevant by shutting down abortion facilities that want to commit abortions in the third trimester. The DuPont Clinic, which is a D.C.-based abortion facility, has promised to open an all-trimester facility in LA in the fall of 2023. The Pro-Life San Francisco team has already been able to locate where this facility will be stationed, and with the help of Survivors [of the Abortion Holocaust] LA, we will be able to strategically prevent them from ever opening their doors.”

Ever since middle school, Jennefer Russo wanted to be a doctor—by the time she entered college she knew she wanted to be one who performed abortions. The reason was simple. As she told Ms., “I grew up watching the impact that abortion had on the women in my life, and I saw that it allowed them to have autonomy and relative control over their lives.”

Russo finished high school in spring 1990—meaning her entire medical education took place during the deadliest decade American reproductive healthcare has ever known. Between the time she started studying biology at Cornell University until the day she graduated from George Washington University’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences (where she served as president of its chapter of Medical Students for Choice from 1998 to 2001), antiabortion terrorists had murdered four clinic doctors, a clinic volunteer, a clinic security guard and two clinic receptionists. From 1990 through 2001, there were 17 attempted murders of abortion providers, according to the National Abortion Federation.

A lot of medical students who’d planned on becoming comprehensive reproductive healthcare providers would have changed course. No doubt many did. But Russo’s resolve hardened.

She had been working as vice chair of clinical affairs for the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. But toward the end of 2022, she began providing care at the DuPont All-Term Abortion Clinic in Washington, D.C.

The previous year, Texas legislators had passed “The Texas Heartbeat Act,” which bans abortion after six weeks’ gestation—when many women don’t even know they’re pregnant. All of a sudden, DuPont’s volume went up with patients seeking second- and third-trimester abortions, as was the case at the other all-term clinics in the U.S.

The clinic staff quickly figured out what was going on: Women from all over the country, including Texas, who didn’t realize they were pregnant within the six-week window needed to travel out of state to obtain an abortion. Because 75 percent of abortion patients are low income, according to a 2014 study by the Guttmacher Institute, and nearly 60 percent already have children, per 2019 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the situation for these patients was extremely difficult.

They would need to obtain childcare, time off from work (most likely unpaid) and transportation, not to mention enough money to pay for the abortion itself. Inevitably, it took these women time to gather all the resources they needed to have an abortion—which, in the cruelest of ironies, is a procedure that gets exponentially more expensive as a pregnancy progresses (from about $600 in the first trimester to anywhere from a few thousand dollars to more than $25,000 in the third).

Due to demand, some patients were having to wait as long as four weeks for an appointment at DuPont, pushing them even later into their pregnancy. So Russo began looking for a site for a second DuPont Clinic—specifically in California because of its strong abortion-rights laws, and relatively near the Los Angeles airport, which serves far more passengers than any other in the state.

Early in summer 2022 (right around the time the Supreme Court issued its Dobbs decision), Russo learned that a suite in a medical building located at 8920 Wilshire Blvd. in Beverly Hills was available. She began negotiations with the owner, the real estate investment trust Douglas Emmett, and on June 30, DuPont sent a letter of intent to the company to lease a suite there. It read: “Use: The DuPont Clinic is a private referral center for all-trimester abortion care.”

On Sept. 25, 2022, Douglas Emmett signed the lease with DuPont.

On Nov. 16, 2022, exactly one week after Turner posted her call-to-arms video, PLSF’s social media accounts reported that the first preemptive strike to “prevent [the DuPont Clinic] from ever opening its doors” had been successfully executed. A group of vandals wheat-pasted flyers all around the medical building where DuPont Clinic LA had leased space. Many of the flyers denounced DuPont’s doctors as “MURDERERS,” “KILLERS” and “CHILD ABUSERS,” and featured a QR code beseeching the building’s tenants and neighbors to join “Project DuPont.” The antiabortion extremist group Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust (often referred to as just “Survivors”) took credit for the action.

Ms. could not find any evidence that in the days after the flyers went up even a single resident of Beverly Hills contacted the city council, police department or the owner of 8920 Wilshire Blvd. to complain or even express concern about an all-term abortion clinic moving into the community. Nor, it appears, did anyone who already had offices in that medical building: physicians, including a family practitioner, a pediatrician, a concierge doctor and another abortion provider (one who did only first-trimester procedures).

Building staff may have notified law enforcement about the flyers, as did one other person: Russo. As soon as she heard about it, she reached out to the FBI’s Civil Rights Division. She knew that in many cases the flyers are just a nuisance, but in others they’ve been harbingers of horrors to come. Flyers had been papered in the local communities of American doctors who were subsequently killed by extremists.

Russo was put in touch with the Los Angeles FBI office, which in turn connected her to Beverly Hills Police Department detective Mark Schwartz, who explained to Russo that the department had not recently seen any major antiabortion activity and that this wasn’t a primary focus for the BHPD compared to other city threats. Still, he promised that the BHPD was ready to protect DuPont, its staff and patients.

Russo remained on edge. But in the days, weeks and months that followed, nothing else happened, aside from a few social media posts by PLSF and Survivors.

In fact, between December 2022 and early April 2023, things were going as expected for DuPont Clinic LA. Various Beverly Hills departments and agencies efficiently issued the clinic a flurry of permits, approvals and licenses, including a business license. The Beverly Hills tax department signed off its emails by saying, “We wish you much success with your business.”

Plans were progressing—Russo began to think she’d been right to choose Beverly Hills as the DuPont Clinic’s Los Angeles home.

The timeline of events that follows was compiled from public interest records requests filed by Beverly Hills for Choice, social media posts by#STOPDuPont, and a complaint and stipulated judgment filed by California Attorney General Rob Bonta following a yearlong investigation by the California Department of Justice. It begins in April 2023 when the #STOPDuPont Clinic page appeared on Facebook, and ends on June 12 when the DuPont lease was rescinded. It would take only two months to stop the DuPont Clinic from opening.

April 10:

Tim Clement, the outreach director of Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust, claims credit for using a high-powered projector to display the words “MURDER MILL” on the side of 8920 Wilshire Blvd.; images of the display are then posted on the Survivors’ social media channels, calling for others to help “stop this horrific murder mill from being established.”

April 11:

Seeing Clement’s posts, DuPont’s chief medical officer reaches out to the FBI, which then contacts the BHPD about the intensifying targeting of the building. According to the California attorney general’s complaint, an FBI agent soon shares background on Clement with the BHPD, detailing his affiliations and multiple arrests earlier in 2023, including on Jan. 31 for the physical disruption of the annual Walgreens Board of Directors and Shareholders meeting to protest the pharmacy’s sales of the abortion pill mifepristone; in February with other Survivors for a disruption at a hospital affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, a major research institute and reproductive healthcare provider; and on March 6 for participating in the invasion of an abortion clinic in Sacramento, Calif.

April 17:

The BHPD chief emails the city manager to ask if they can schedule a closed city council meeting. The city manager responds no with a sad face—adding that the city attorney said it would be illegal to do so.

The next evening, #STOPDuPont representatives, including Tasha Barker, speak at the city council meeting, demanding that Beverly Hills prevent DuPont from opening. During her comments, which include inflammatory falsehoods about DuPont, Barker explicitly asks the city to place a hold on DuPont’s permits and put the question of the clinic opening on the council’s agenda. During the meeting, city council member Sharona Nazarian emails the Beverly Hills city manager in real time, asking, “How did this get through?”

April 19:

Barker follows up with Nazarian by email, requesting a meeting about DuPont. Nazarian responds immediately, thanking Barker for her testimony the night before and for her email. Nazarian loops in the city attorney and the city manager, who emails Barker: “We would be happy to meet with you. I am copying [the city’s office manager] to schedule a time.”

April 21:

The office manager reaches out to a Douglas Emmett senior vice president to set up a meeting with him, Police Chief Mark Stainbrook and the city manager to “discuss one of their BH properties with him and go over some safety concerns.”

Three days later, the office manager emails the company again, suggesting a meeting on May 3. A few hours later, another email is sent to Douglas Emmett, saying that the city manager would like to meet sooner rather than later and asking about availability “tomorrow 4/25 at 3pm?”

(Sometime between April 18 and 24, the city attorney directs the permitting department to put a hold on DuPont’s permits—permits that had already been approved by the Beverly Hills Community Development Department. When DuPont requests copies of the approved permits on April 24, it’s alerted that the city attorney placed a hold to determine “whether the proposed use is allowed or not.”)

April 25:

When the city manager, deputy city manager and police chief meet by phone with Douglas Emmett, notably neither Russo nor any other representative of the DuPont Clinic is invited to join. During the call, the city representatives claim “that with DuPont as a tenant, the Building could be subject to protests, bomb threats, and ‘lone-wolf’ active shooters,” according to the attorney general’s investigation—though there is no record that any threat of actual violence took place. The city’s representatives say they have “very limited resources” and aren’t “going to be a substitute for [Douglas Emmett’s] private security,” per the attorney general’s complaint. The city also highlights concerns that protests against DuPont will result in Beverly Hills receiving negative media attention.

At the end of the call, the city representatives ask the company directly if its lease with DuPont is “100 percent happening” and whether there is some way to “unwind” the lease.

April 30:

PLSF escalates its actions against DuPont, posting an hourlong video on its social media outlets during which Turner explains how the group intends to shut down DuPont with a “giant Operation Rescue-style sit-in” before it opens:

“It is more important to stop them before they start because once they start, it is harder to get them to stop. If we can raise hell, we can make everyone else in the medical complex say, No, we don’t want abortion people here because there’s going to be protests all the time.”

The video comes to the attention of the BHPD, which also learns that the names and photos of DuPont staff are now being posted on Survivors and PLSF social media pages and websites.

May 19:

#StopDuPont leaders meet virtually with the city manager, the assistant city manager, the city attorney and city council member Nazarian. It’s not known what transpires at the meeting, but city representatives had previously scheduled another meeting with Douglas Emmett for May 24.

At some point before the meeting, the city devises a plan to send a letter to the building’s tenants regarding purported safety risks that will result from DuPont’s opening. The idea of the letter originates with the BHPD and is discussed with the city manager and mayor. The letter, to be signed by the chief of police, will lay out four areas of concern “related to public safety and potential safety implications” for tenants and their businesses:

- Privacy: Patients visiting your business have the right to privacy within your suite and common areas of the building.

- Noise and traffic: There may be increased noise and pedestrian traffic in and around the building due to protests or other disruptive activity.

- Criminal activity: There may be violence or vandalism that requires law enforcement involvement.

- Harassment: Intimidation of patients and staff may occur.

May 24:

At the meeting between Douglas Emmett, the mayor, the city manager, the deputy city manager and the police chief, the city expresses its concerns. According to the attorney general’s complaint, “Mayor [Julian] Gold, in particular, used a raised voice to bring up the prospect of bombthreats, active shooters, and the safety of other tenants,” noting that the company would be liable if anything occurs.

The mayor asks Douglas Emmett directly if the company is going to “move forward” with DuPont’s lease and eventual operation in the building. When hearing that, yes, DuPont would open in the fall, the mayor “fell quiet.”

June 5:

During a tour of the building with Russo and representatives from the FBI, BHPD and Douglas Emmett, the city’s proposed letter to the building’s other tenants is discussed. The BHPD captain explains that the mayor is “very anxious” to distribute the letter, and he makes it clear that the city “would even have cadets hand-deliver” the letter to the tenants door-to-door. Douglas Emmett responds that having police deliver the letter is a “really, really bad idea” and would lead to “a thousand questions that these young cadets are not going to be prepared to answer.” The company asks for more time to discuss the matter.

June 7:

Douglas Emmett contacts the city manager and mayor to ask for another call, says it is “working on something” and asks for a pause on distribution of the letter. Gold agrees to pause for one week and, according to the attorney general’s complaint, he thinks to himself, “We’re making progress”—which revealed to state investigators that the city considered the letter to be effective leverage against Douglas Emmett.

June 9:

Clement of the Survivors is featured on a high-profile antiabortion podcast boasting about the campaign against DuPont and announcing plans to lay siege to Beverly Hills:

“Yeah, so, this summer Survivors is partnering with other pro-life organizations and we’re going to actually head it off and just anchor down in Beverly Hills. … What a better way to do it than to go to the gates of hell and face DuPont that’s trying to put this abortion clinic right in our backyard and try to shut it down.”

He prompts listeners to email him for more information on ways to get involved with the planned actions.

June 12:

Douglas Emmett sends a letter to Russo rescinding DuPont’s lease, copying the Beverly Hills mayor and city manager on the email.

July 11:

The BHPD notifies Clement, the Survivors and #StopDuPont representatives that the lease has been rescinded.

The Aftermath

In November 2023, the California attorney general’s office began an investigation into the city of Beverly Hills for violations of the California Constitution and state laws protecting reproductive healthcare access.

In October 2024, the attorney general filed legal action against the city. The filing alleged a pattern of coordinated activities specifically designed to prevent DuPont Clinic LA from opening. A press release from the attorney general’s office characterized the actions of Beverly Hills officials as “reminiscent of those in extremist red states by illegally interfering with, and ultimately preventing a new reproductive healthcare clinic.”

Simultaneously, the attorney general filed a stipulated final judgment as part of a voluntary settlement to “ensure Beverly Hills comes into full compliance with the law and provides a benchmark for local governments to align with.”

To date, none of the extremists who orchestrated the #StopDuPont campaign has faced any legal consequences, despite their role in blocking DuPont from opening its clinic. Meanwhile, DuPont has not been able to recover the $2.5 million it spent on tenant improvements from either Douglas Emmett or the city.

After DuPont sued Beverly Hills to recoup these costs, the city filed an anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) motion, seeking to dismiss the case on grounds that it targets the city’s First Amendment rights and asking for legal fees. Depending on the outcome of the lawsuits, DuPont may end up owing the city of Beverly Hills money.

Great Job Kathy Spillar & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.