Graphics and development by Lucas Waldron. Design by Anna Donlan. Visual editing by Shoshana Gordon and Donlan. Research by Mollie Simon.

Joe Biden Diagnosed With “Aggressive Form” of Cancer

May 18, 2025

Here’s how you can use the Take It Down Act after it’s signed today

May 19, 2025In their last phone call before bed, Janicke Glynn tries to reassure her husband. He is away visiting a sick relative, and a Weather Channel forecast of Hurricane Helene’s imminent collision with the North Carolina mountains is leaving him uneasy. The storm, more than 400 miles wide, is expected to strike their small community the next morning, Sept. 27.

Janicke encourages him to focus on his family up in Boston. That is more important. She is fine. It’s been raining a lot, but the house is fine. Everything is fine. He’ll fly home tomorrow. She will see him then.

“Love you.”

Credit:

Courtesy of John Glynn

Janicke, a 46-year-old French Canadian, isn’t worried. She feels a deep spiritual connection to their home in Yancey County, a remote and ruggedly sublime expanse in the shadow of trendier Asheville. Nestled on a mountainside draped in maple and birch, perfumed by mountain laurel, their property is surrounded by the Black Mountains, ancient protectors of this magical place. Mount Mitchell, the tallest among them — the tallest in the eastern U.S. — is their backyard.

When the power goes out, Janicke lights candles and opens a door. She loves to hear the creek just beyond, a normally burbling carrier of rainfall down the mountain. But after two days of rain, it is starting to roar even before Helene’s arrival. She settles onto a living room couch with a little rat terrier, Troopie, one of their two rescue dogs.

Seven years have passed since she and John first looked at this property. He was thinking about retirement spots by the time they married in 2016 after keeping up a long-distance relationship for nearly a decade. Both were sick of the harsh Northern winters, and Janicke longed to rekindle the bond she’d felt with the natural world growing up in rural Canada. When she got out of the car to look at the property, she heard the creek and felt an instant harmony with the place. It had a 1940s stone house up on a hill, two wood-paneled cottages tucked along the creek and five acres where she envisioned tending lush gardens.

When she wondered if it cost too much, John argued that wasn’t the right question.

“Do you want to live here?” he asked.

“I want to die here, Johnny.”

Credit:

Courtesy of John Glynn

After John falls asleep in his hotel, Helene makes landfall on the Florida panhandle about 500 miles south of the Black Mountains. As its massive bands close in, Janicke stays up listening to the storm and texting a tenant who rents one of their cottages, about 40 yards away right on the creek.

He types, “This shits crazy over here.”

Janicke knows he is anxious. Hours earlier, he sent her a screenshot of a National Weather Service post on Facebook that warned Helene could become one of the region’s worst events “in the modern era.” He worried about what the forecasted 9 to 14 inches of rain, expected to fall onto the high peaks in the morning, would do to the already swollen rivers.

The post described “catastrophic, life-threatening flooding.” Her response was typically upbeat: “Thanks, Mother Nature is powerful!”

He’d been thinking he might drive to his brother’s place in Charlotte, but Janicke offered up her house if the cottage flooded. They hadn’t heard of evacuation orders or seen other signs to indicate anyone else seemed terribly concerned.

As the hours pass and Helene closes in, Janicke’s tenant texts her, “My nerves are shot.”

He soon shows up at her door with a bag and his 15-year-old cat, Mama Kitty. The creek is pounding the foundation of his cottage and seeping inside. Its increasingly violent flow fills the air with a searing white noise as it races down the mountain past houses, horse pastures and barns. Cattail Creek Road, the main way in and out of the area, winds right alongside it.

Few people along Cattail fully realize the looming danger. Some of them sleep. One man laments that he will miss his flight in the morning. A woman downloads ebooks to have something to occupy her time if the internet goes out. Another assures a loved one that the storm will quickly pass before dawn.

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

Like Janicke Glynn, Brian Hill lives close to Cattail Creek. Closer, even. His century-old farmhouse sits about 15 yards from the banks. Unlike Janicke, he is starting to worry. Late the night of Sept. 26, he peers outside and is caught off guard by the creek’s fast-rising water.

Whoa, it’s really full, he thinks.

But as far as he knows, Cattail Creek has never flooded the house where he lives with his wife, Susie, and 9-year-old daughter, Lucy. Both are asleep. He tries to be quiet, but a sudden noise jolts him — boom, boom boom. It shakes his house like fireworks. He peers outside and realizes that somewhere up the mountain, the water is dislodging boulders. They are crashing down.

Around midnight, someone knocks on their door. It’s a firefighter warning that the creek has risen so high that it blocks the road in one direction. Soon, there could be no way out. “I can’t tell you what to do,” the man says. But he urges them to move to higher ground.

Brian and Susie grab their little girl and their dog, then rush out to their pickup truck. In the darkness, they drive up a hill that overlooks their property.

Up the north fork of Cattail Creek, as the water rises, no first responder knocks on Janicke Glynn’s door.

Overnight, Helene churns across Georgia, then clips the northwest corner of South Carolina. Before sunrise, the storm collides with the Black Mountains, particularly the towering frontal wall called the Blue Ridge Escarpment. The high peaks shove the massive storm up into the cooler atmosphere.

Up in the chillier air, that water condenses. As Helene’s bands lash the Black Mountains, the storm begins to dump enormous amounts of water onto the already saturated peaks. In the morning, from 7 to 10 a.m. alone, about 8 inches of rain will fall atop Mount Mitchell. Because all that water must go somewhere, the deluge creates two critical threats: flash flooding and landslides. Both pose extraordinary danger. But landslides can destroy with far less warning.

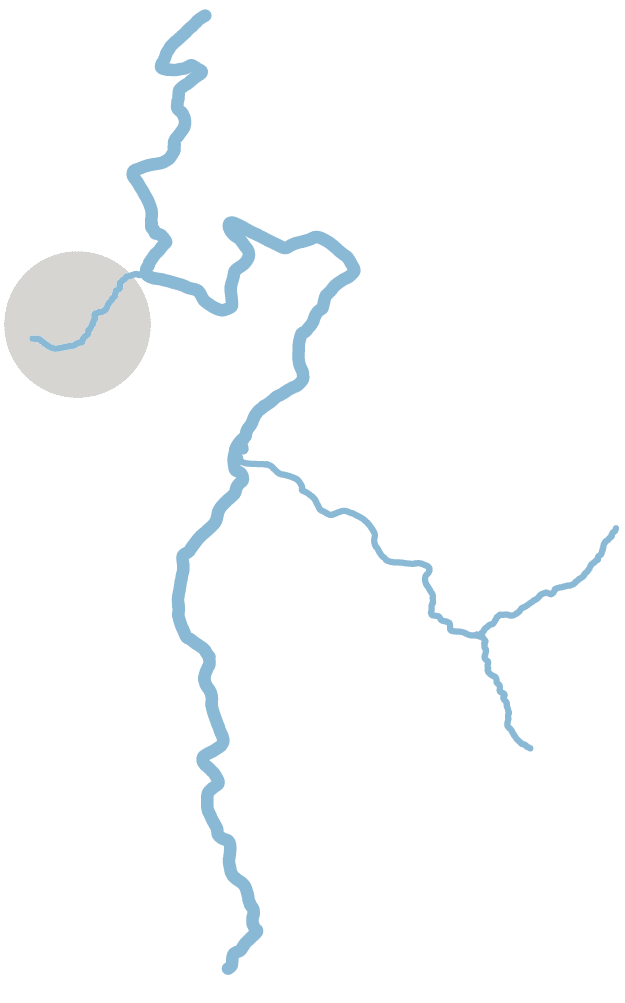

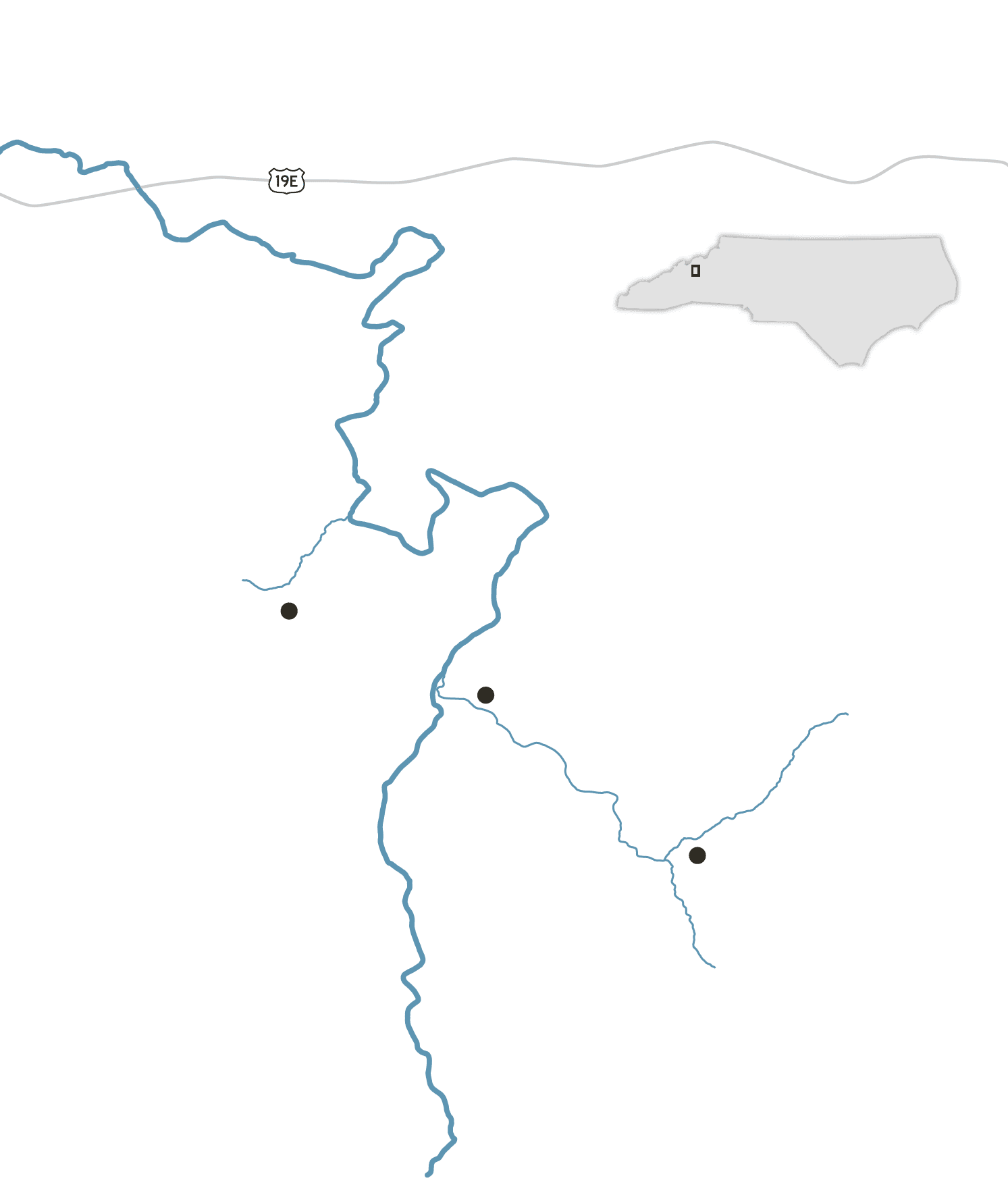

The Cane River is about to get pummeled by both. Hemmed in by mountains, it forms the spine of one major valley in Yancey County. One of its tributaries, Cattail Creek, extends off that spine like an arm reaching east. Another, Tudy Creek, reaches west.

Several peaks wrap around Tudy Creek. High atop a particularly craggy one, the rainfall gets a toehold beneath soil clinging to a very steep and slightly concave slope of rock. Soil and rock will begin to slide with the water. Following the creekbed, the flow will gain velocity and weight and hurtle downhill with enough power to uproot trees and dislodge boulders.

In its path, a group of longtime neighbors live in a tranquil enclave of homes.

Among them is Ray Strickland, who retired a decade ago after 37 years as pastor of a local Baptist church. A hardworking man who still helps at the family construction company, Ray lives by the Scripture he often used during his first year at Laurel Branch Baptist, Psalm 66: “Make a joyful noise unto God.” His wife, Susan, a sweet woman with short grey hair, worked as a dental hygienist and performed as a clown named Jubilee at hospitals, nursing homes, parties — even the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Along with several of their neighbors, they raised their children here. Two newer neighbors moved here from Florida, weary of all the hurricane threats.

Credit:

Courtesy of Ginnie Strickland Beverly

On Friday morning, the neighbors are all in their homes. Little do they know that the swath of land on which their houses sit was created, at moments back in geological time, by landslides. They had careened down steep slopes, probably following creekbeds, and dumped huge amounts of material here. That created a flatter spot to build houses in this otherwise rugged place.

In a storm like Helene, it’s also a precarious place to be. If the topography enabled a landslide here before, it could do so again.

Given it already has been raining a lot, Ray and Susan worry most about their 43-year-old son, Aaron, who lives on the other side of the mountain with his two young children. In April, water seeped into his basement.

When Ray texts Aaron around 7 a.m., just as Helene is arriving in Yancey, he responds, “flooding.”

The curt tone isn’t like him. He and his parents normally stay in daily contact, so Ray and Susan figure they’ll try him again later.

Then their cell service cuts out. Without it, they’re among those in pockets across the county who don’t get the National Weather Service’s 8:50 a.m. emergency warning for Yancey: “The risk of life-threatening landslide activity continues to increase. … This is a PARTICULARLY DANGEROUS SITUATION.”

The storm worsens. Wind roars. So much water flows down the mountain that Tudy Creek — normally about 4 feet across — swells and merges with another creek to form a violent river that rages down the road between them. Water seems to gush through every crevice in the mountain bedrock.

Around 9 a.m., when the deluge settles between the storm’s bands, Ray heads to the back of their house where rocks are hitting the foundation. Susan ventures outside near the road, then meets Ray on their front porch. They’ve never seen anything like this. While Ray holds an umbrella, Susan records video with her phone.

Ray glances up. The tops of towering trees shake. Then a 20-foot wall of trees, boulders and mud rockets straight at them.

“Ray!” Susan screams.

First responders were out overnight blocking off access to roads as they vanished beneath two of Yancey’s major waterways — the Cane and South Toe rivers — and the creeks that feed them. In this rural county, home to 19,000 people, the firefighters are all volunteers. So is the rescue squad.

The county commission recently received a draft of an emergency operations plan that warned, “A mass casualty event has the potential to quickly overwhelm the limited existing emergency medical resources in Yancey County.”

Now, on Friday morning, the wind and rain turn fierce. At 45, Sheriff Shane Hilliard hasn’t seen anything like it during his entire life here. Just before 8 a.m., he texts his mother to check in, but he doesn’t get a response. His parents live right on the South Toe River in the house he grew up in. His 92-year-old grandmother lives alone next door.

Rain whips downtown Burnsville, the county seat where the sheriff and other officials gather in the Emergency Operations Center. This command post is basically three desks, a conference table and four big TVs on the wall in a building near the courthouse.

In an adjacent building, calls pour into the county’s 911 center.

Landslides claw down the mountains. Hurricane-force winds splinter trees. Rivers snatch cars and rip apart homes. People climb into attics or swim through windows. A firefighter makes a distress call as the Cane River near Cattail Creek swamps his trailer. A deputy trying to rescue a family from their flooding home becomes trapped with them.

Dispatch blasts out an all-call: First responders must get off the roads. It’s too dangerous.

Jeff Howell, Yancey County’s emergency management director, watches the radar as storm imagery shifts to red. Helene’s rainfall now resembles blood-filled lungs hanging over the Black Mountains.

Howell, who has deep roots in the area, took the job seven years ago after three decades in the Army and Army Reserves. He had no experience with emergency management, so it’s been a lot of learn-as-you-go. For years he asked for extra hands, but as Helene approached, the department was just him and a part-time employee.

Now Howell faces the biggest test of his time in the office.

Over the past week, he watched each forecast turn more ominous, with western North Carolina in a bullseye of the heaviest rainfall. Yesterday around noon, a lead meteorologist in the National Weather Service’s regional office ended its final briefing before Helene’s arrival with a grim, “Good luck, everyone.”

The office also issued a public statement that warned, “Landslides, including fast-moving debris flows consisting of water, mud, falling rocks, trees, and other large debris, are most likely within small valleys that drain steep slopes.”

Around the same time, weather service staff also took to social media to post the dire message that Janicke Glynn’s tenant had seen: “This will be one of the most significant weather events to happen in the western portions of the area in the modern era.”

“We cannot stress the significance of this event enough,” it added. “Heed all evacuation orders from your local Emergency Managers.”

Credit:

Courtesy of Zachary O’Donnell

Unlike in South Carolina, where the governor typically makes evacuation decisions, in North Carolina, local and county governments primarily make them. Howell, the official who would recommend evacuation orders to the county commission chair, didn’t do so. In this largely conservative place — fresh off a culture war battle over a Pride display at the local library — he didn’t think the chair would go for them. Nor did he think residents would heed orders, given many locals’ disdain for government mandates and their pride in self-reliance.

People who survived Helene say it’s true that not everyone would — or could — have heeded an order. But some say they would have left, or at least prepared better. Many, including those living in high-risk areas and caring for young children and frail older people, didn’t evacuate because they didn’t see clearer signs of urgency from the county.

By nightfall on Sept. 26, the day before Helene struck, three nearby counties issued mandatory evacuation orders for certain areas and at least five issued voluntary ones. Among Yancey’s rural neighbors, one of the most robust responses to Helene came from McDowell County. Officials there issued voluntary and mandatory evacuation orders for specific areas, launched two door-knocking campaigns to warn people in high-risk places, and put out flyers in English and Spanish that warned of life-threatening flash floods and urged all people in vulnerable areas to “evacuate as soon as possible.” Many did so.

Yancey also did some door knocking. Howell joined first responders urging people in the most obviously dangerous places to consider leaving. Not everyone appreciated the warning. Howell got an earful before finally convincing a man to leave a campground almost encircled by the South Toe River.

Like officials across the region, Howell took to Facebook as well. Around lunchtime on Sept. 26, he shared the weather service’s latest grim briefing and suggested people make plans to stay somewhere else if they live near flood-prone areas. But while the weather service aimed to alarm people into action with its dire post, Howell thought it best not to panic them.

So he softened the message, adding, “This information is not to frighten anyone.”

About 150 yards up the hill from their century-old house, Brian and Susie Hill huddled in their pickup truck with their little girl and dog overnight as rain poured and darkness enveloped Cattail Creek.

Now, a few hours after sunrise, they watch their house drown.

They would have left if the county had issued a mandatory evacuation order, especially for Lucy’s sake. Still, if they hadn’t gotten that middle-of-the-night knock on the door from the firefighter, it could have been worse.

Susie hands her cellphone to the child to distract her from the sight beyond the truck’s windows. The creek rages. It surrounds their house, pounding it with waves and ripping the porch and doors off. Windows cave in.

They bought the white farmhouse, with its mountain views, a year ago and have been busy restoring it — slowly, on two public school teacher salaries. This is a place where their daughter can run outside on 6 acres, where a neighbor’s horses graze in a field next door, where they can gather around the fire pit at night and listen to the creek. Susie raises chickens and tends a garden filled with asparagus, blueberries and strawberries.

People like Susie and Brian come to Yancey County, and stay here, and die here, for the majesty of two forces: the mountains and the rivers. The ancient mountains protect; the rivers nourish. They provide hiking, whitewater rafting, kayaking and the meditations of so many tranquil creeks.

Now it feels like both have betrayed them. Along Cattail, people watch the landscape of their happiest memories vanish beneath floodwaters.

Janicke Glynn and her tenant, who is sheltering at her house, were up all night listening to the storm. He feared what was happening to his cottage down by the creek. Janicke remained calm, lighting candles when the power went out and trying to ease his worry. He’d gone through a tough time last year, losing family and dealing with heartbreak, and they’d become close friends.

But at the first crack of daylight, his emotions fray when Janicke ventures outside to pick up branches and sticks. Rain still drenches the mountainside, and wind gusts with enough force to bend trees. Janicke wants to keep her paradise unmarred. He doesn’t want anyone to get hurt. When he runs out after her, yelling at her to come back inside, she reluctantly complies.

When the rain and wind ebb just before 10 a.m., they step outside to assess the damage together. Hemlock hedges block the view of his cottage, so they head down toward it. The creek has calmed a bit as well. As they slip closer, they see the windows are busted and his belongings dragged out. Everything inside is churned up.

Janicke is fearless. But her tenant is unnerved. He thinks they are acting way too comfortable. Standing beside the battered cottage, he hollers, “I think we should go back to the house!”

Janicke steps closer to the water.

“We need to go back now!” he screams.

A gush of water rushes under her. From a dozen feet away, she turns toward him. As she does, the current rips down the cottage and then swallows them both.

Ray Strickland wonders if he is dead. The retired pastor realizes he is in a small pocket of empty space encased in debris from their home. Light reaches through a hole. Something pins his leg.

When he yells to his wife, Susan, she does not answer.

An opening. The light. If he leaves his boot, he can wriggle free. When he climbs out of the pile, destruction surrounds him. A car alarm blares. A smoke alarm screams. Water rages by.

Ray sits on a boulder, dazed. Drywall sticks out of one ear. Blood runs down his arm. What looks like road rash covers his skin. Yet he feels strangely serene. If God takes him now, that’s his will.

Some time passes. Then a man’s voice. Someone is yelling his name. It is Pete Lewicki, who lives in the next house down from him. But Pete is across a wide river blazing past the rubble. Ray hollers at him to get back.

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

Pete doesn’t listen. When he was in the Navy, he worked in search and rescue. Now that training kicks back in. To reach Ray, he and his 24-year-old son haul over ladders and move logs to create a makeshift bridge. Pete slips crossing the slick ladder. Floodwater tears at him as he climbs back up.

When he reaches Ray, Pete finds the man is shaking — and is eerily calm.

Once they get Ray out of the wreckage of his home and into their house, Pete’s wife wraps him in a blanket and finds dry clothes for him. Pete promises he will be back.

A landslide barreled through their enclave. Ray’s house is gone. So is the house just above Ray’s at the top of their road. So is its freestanding garage apartment, where an older man named James Andrews lived. Trees and boulders block the way. Pete makes it, then spots James. He is dead, pinned beneath a huge tree. Pete covers the body with a bedsheet in the debris.

As Pete heads back to his house, Ray comes outside. He is thinking more clearly now and is certain his wife, Susan, is in the mound of debris where he’d been trapped. They had been near each other when the landslide hit. He leads Pete and two other men from down the road to the small hole he’d crawled through in the ruins. The men inch down into it.

Pete spots Susan. She is 3 feet down from where Ray’s blood pooled in the wreckage. It’s clear she has died.

He remembers her smile, which she used to brighten people’s lives. Almost every day, she and two neighbor ladies, both recently widowed, walked up and down the road together. When they walked by shortly after Pete moved in, Susan stopped and came over to give him a big, welcoming hug. Pete, a veteran with neck tattoos who has post-traumatic stress disorder, deeply appreciated her gesture.

They all know that Susan is buried too deep to get her out themselves. Ray, her husband of almost 50 years, tells them to stop trying. It’s a miracle he is alive, and he doesn’t want anyone else to get hurt.

Looking across the ruins, Pete sees the landslide’s path down the steep slope above their road. The debris flow had barreled more than a mile down the mountain, leaving an expanse of mud and rocks. He had never seen this magnitude of destruction, not even during his 40 years living in Florida, where hurricanes repeatedly flooded his home. A massive mound of trees and remnants of the destroyed houses sits piled against a neighbor’s garage. A widow lives there with her parents, who are 86 and 89. Pete heads over to check on them.

When he gets there, he sees that Marie-France Herman, the woman who lives at the top of the road, is there with them. She is caked in mud with a black eye and a nasty gash on her ankle. Inside the house, they are all slogging through mud almost to their knees. But getting out means crossing the landslide’s path to reach another neighbor’s house, an A-frame that looks, somehow, unscathed.

After many precarious moments, they all make it. Ray joins them.

The neighbors share notes about what they all just survived. When the landslide hit, Marie was looking out at the worsening storm through an antique door. An 81-year-old distant relative in poor health who lives with her was sitting nearby at the kitchen table when Marie spotted trees toppling down the mountain like dominoes.

The next thing she remembers, water slammed into her. She expected to drown. Instead, she got her head above water and climbed onto some logs.

She has lost everything, even her husband’s ashes. And she doesn’t know where her relative is.

The rain finally lets up by late morning on Sept. 27, but the rivers and creeks rage with so much water flowing down the slopes. Hilliard, the sheriff, heads to the 911 center, which is running off a generator. The calls coming in terrify him and the other county leaders. Floodwaters fill homes. Rivers ravage roads. People watch neighbors get swept away in cars and on foot. Landslides careen down slopes.

At 10:51 a.m., the 911 center suddenly falls silent.

The sheriff and others look at one another: What just happened?

What was left of Yancey’s cell service has now failed. Landlines are already out. So is the internet.

Emergency responders are left with only their radio system. And that is quickly overwhelmed. It takes eight to 10 tries to get a call out, if they can even get one out. Many just get error tones.

Finally, somehow, the sheriff gets through to the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association director in Raleigh. “I need help!” he pleads.

But help won’t be coming, not any time soon.

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

County-to-county communications across the region barely function. The state Emergency Management agency is severely understaffed, slowing its response.

As Helene’s deluge flows down the Black Mountains, it inundates rivers on all sides of the peaks, claiming dozens of lives and destroying communities in every direction. One county over from Yancey, a family of four — including two little boys — are swept to their deaths while fleeing their home. To Yancey’s south, floodwater swallows little towns en route to Asheville. A nearby landslide kills 11 people from one family and two firefighters coming to their aid. Raging water decimates downtown Chimney Rock, a tourist village, heading to Lake Lure, a resort town. The National Weather Service blasts out an alert: “DAM FAILURE IMMINENT!”

Minutes later, at 11:15 a.m., state transportation officials tweet, “All roads in western NC should be considered closed.”

Hilliard knows little of this is happening. With the 911 center silent, cellphones and landlines and internet all down, officials inside the Emergency Operations Center abandon it. The command center is useless. They cannot help anyone from here.

Not long before noon, the sheriff heads out with a crew in the county’s large armored military surplus vehicle. They cannot get far. Downtown Burnsville is an island. Roads and bridges in all directions are submerged, washed away, blocked by trees or smothered in the liquefied mud of landslides. Places like Tudy Creek and Cattail Creek are unreachable.

Credit:

Courtesy of Douglas Rodgers

Everyone in the vehicle falls silent. A look the sheriff has never seen falls over their faces: They are afraid. His radio squawks. Someone from the South Toe Fire Department hollers his name. Firefighters made it to the river where the sheriff’s parents and elderly grandmother still live.

His parents’ house is gone, washed away. And they cannot find his parents.

He yells for them to check next door at his grandmother’s house.

They tried, the voice says. But her house is gone, too.

On Sunday morning, two days after the storm hit, Aaron Strickland still hasn’t heard from his parents. After Helene subsided, he and his girlfriend went to the local fire station where her son, a volunteer firefighter, worked overnight. He and other firefighters returning from distress calls described an apocalyptic level of destruction.

But none of them mentioned Tudy Creek, and Aaron figures that’s a good thing.

When his girlfriend finds a county building with working Wi-Fi, he’s relieved to finally make some calls. He dials his parents, but the call won’t go through. He is able to reach his sister, Ginnie Strickland Beverly, who lives a few hours away in Winston-Salem.

Ginnie is distraught. Like so many people unable to reach loved ones trapped inside Helene’s destruction zone across western North Carolina, she has been scouring news sources and Facebook, gathering scraps of details about what’s happened. She heard crews airlifted a dead person out from Cattail Creek. But she hasn’t been able to find anyone who reached Tudy Creek.

“Have you made it up to Mom and Daddy’s yet?” she asks.

Worry sets in. Aaron hangs up and hurries out. Maybe he can get there himself.

At the first bridge, police are directing traffic, so Aaron stops to see what he can find out. This is a small community, and he sees familiar faces. One is the mother of a childhood friend who lives at the base of Tudy Creek. Aaron has known her his entire life. When she sees him, she hurries over and wraps him in a hug.

“Honey, I’m so sorry,” she says. For a moment, they look at each other. Aaron isn’t sure what she means.

“Your mom is gone,” she blurts out. His father, Ray, is hurt. She doesn’t know how badly. Her son just made it down from there. A landslide. Some bodies. Aaron doesn’t hear much else.

Desperation consumes him. So does a plan.

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

Normally, it takes 20 minutes to drive around the mountain from his place to his parents’ house. But as a crow flies, it’s more like 2 or 3 miles over the mountain. Growing up, that mountain was Aaron’s playground.

He and his girlfriend’s son, the volunteer firefighter, drive to an airstrip at the top of the mountain, then hike down toward his parents’ house. As they slip on slick mud and wet leaves, fear propels them. Aaron fights back images of his father with a head wound or broken bones, or worse. He shoves away thoughts of his mother, for now.

They come upon what looks like a landslide, its mud like quicksand pocked with holes and mangled trees. To Aaron, it appears 100 yards wide. They must go around it over toppled trees and boulders.

Finally, they spot a creek. It flows down a channel scoured out that looks 30 yards across and 20 feet deep. Aaron has hiked all over these mountains, and the only creeks up here are slim little things 3 or 4 feet wide, a few inches deep.

“Where are we?” he asks.

At last, they see an old logging road. There is only one on this mountain, and it leads to the top of his parents’ road on Tudy Creek. But when they reach where it should dead end into their street, piles of mud, trees and boulders 20 feet high and 50 yards across block their path. When they scale it, Aaron looks out over the expanse of fallen trees, boulders, mud and debris.

Oh my God.

He clambers down toward the spot where his parents’ house — the home he grew up in, the tan split-level with the long front porch — should be standing. Terror replaces his desperation.

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

The woman who told him about his mother’s death also said his father was at their neighbor Rita Thacker’s house. Aaron’s heart thunders. His stomach churns. He scrambles up the steep, muddy bank toward Rita’s. Huge fallen trees block his view. Climbing through dense branches and leaves, he looks for holes to wiggle through.

Finally he sees Rita’s beautiful A-frame. He hears voices. He hadn’t considered that other people might be there with his dad and Rita. Busting through the last branches, he pops out looking at her backyard.

Rita is standing right there with another neighbor and that woman’s elderly parents. They turn to the commotion. Aaron spots his dad.

Ray is standing with his back to him. But he is standing. He is talking. He is OK.

Aaron sprints over and wraps his arms around his father. No contact for days, terrible, awful stories coming in, running on fumes, little sleep, the shock of his mom’s death, fear for his dad’s safety, inability to communicate, all of that bursts out in the tears of this moment.

He has rarely seen his dad with a three-day scruff, so he sets his hand on his face to feel it. “It’s the best you’ve ever looked,” he says.

With no way to contact anyone, no running water or power or passable roads, the neighbors relied on each other since the landslide. One is a nurse who treated the physical wounds. Pastor Ray has fed spiritual needs — and hauled 5-gallon buckets down to gather water to flush the toilets. Rita has a gas stove, so they cook. This morning, they made waffles.

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

As his adrenalin ebbs with relief, Aaron turns to the destruction.

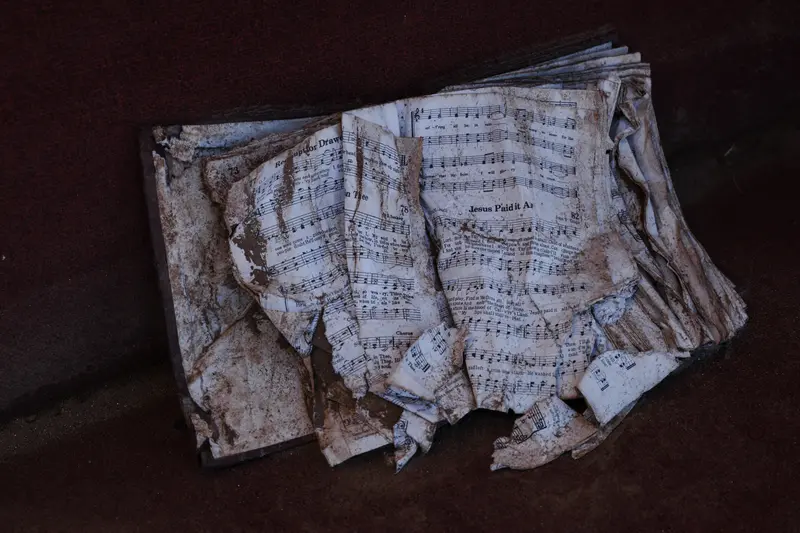

His parents’ house looks like a giant hand crushed it. The body of Aaron’s 71-year-old mother, the woman who took him with her to clown conferences when he was a kid, is buried so deep in the mound of debris that it will take heavy equipment to get her out. He finds one of her old Bibles.

Almost a mile down the mountain, neighbors find the body of Marie’s elderly relative.

Janicke Glynn’s husband landed in Charlotte shortly after the storm hit, and during the two days since he has turned frantic. He hasn’t been able to reach her — or anyone else in the area. Nor can he get back to Cattail Creek. Every road he tries is blocked by flooding, landslides and police who turn him back. He is staying at a hotel 80 miles from Burnsville with no electricity.

Finally, on Sunday afternoon, he gets a text from their tenant. It comes from someone else’s phone, a newer one that can get a satellite connection.

“I’m so sorry Janicke is gone,” it reads.

Their tenant adds that he almost died too. When the cottage collapsed, a freight train of water and mud consumed Janicke. But when it smashed into him, it shoved him closer to the main house. He grabbed a spindly shrub and clung to it, praying that it wouldn’t snap and he might see his family again.

Eventually, screaming for help, he pulled himself out. But he could not find Janicke.

Now, he is trying to hike to the local fire station for help. He has no glasses, his skin is shredded in spots, and he’s bleeding from a deep gash in one knee. The station is a few miles away but feels unreachable with no roads and infinite destruction to cross. He promises John he will call when he can get service.

Credit:

Courtesy of John Glynn

In Yancey County alone, 11 people died due to Helene. Per capita, that’s twice the rate of deaths as any other county in North Carolina. Yancey bore the brunt of the storm’s highest recorded wind gust and its highest recorded rainfall — both on Mount Mitchell. Thirty inches fell there over three days at the most inundated site, half of it before Helene’s arrival. Hundreds of landslides raked the county’s slopes.

Across the South, officials attribute 250 deaths to the storm. Of those, 107 died in North Carolina. Helene is the deadliest inland hurricane on record, by far.

Freshwater flooding was the top killer.

The sheriff learns his parents and his grandmother are alive after a harrowing escape through floodwaters. But across the South Toe River, a family of four who came to Yancey after fleeing the war in Ukraine were swept away.

Credit:

First image: Courtesy of Ginnie Strickland Beverly. Second image: Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica.

Jeff Howell, the emergency management director, retired earlier this year and still remains haunted. During his time in the Army and Army Reserves, he was deployed three times for three wars in three decades. None got to him like Helene. He couldn’t shoot back at the storm.

In hindsight, he feels that he and others notified folks as best they could given the unprecedented nature of Helene’s assault.

It’s true that no one alive had ever seen destruction of this magnitude in the region. But the National Weather Service warnings about the storm — “catastrophic, life-threatening flooding” and “severely damaging slope failures” and among the worst “in the modern era” — proved prescient.

When Brian and Susie Hill emerged from their truck the morning of Sept. 27, they found their once-gorgeous property resembled a moonscape of mud and rocks. Inside their home, it looked like someone put the contents of their lives into a blender. But when they slogged into their daughter’s bedroom shortly after the floodwaters receded, they found her stuffed animals still on the top bunk where she left them before Helene hit. They were perched just above the water line and were the only thing she cared about salvaging.

The little girl had been so stoic. But when they left the house with her stuffed animals, she finally cried.

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

About a week later, the Hills are living at a friend’s house. Susie is grateful that Lucy can play with the family’s three young sons and keep her mind off things. The sadness of all they have lost subsides for a moment — and is quickly replaced by a new fear.

She and Brian live on public teachers’ salaries. They have 28 years left on their mortgage. Because their house isn’t in a flood zone, they don’t have flood insurance.

She gets a pause on their mortgage. But it’s only for three months. She can think of just one place to turn to next for the magnitude of help they need. On her cellphone, through the fog of trauma, she types in “FEMA.”

Credit:

Juan Diego Reyes for ProPublica

Great Job by Jennifer Berry Hawes, with additional reporting by Cassandra Garibay & the Team @ ProPublica Source link for sharing this story.