Media Matters weekly newsletter, May 16

May 16, 2025

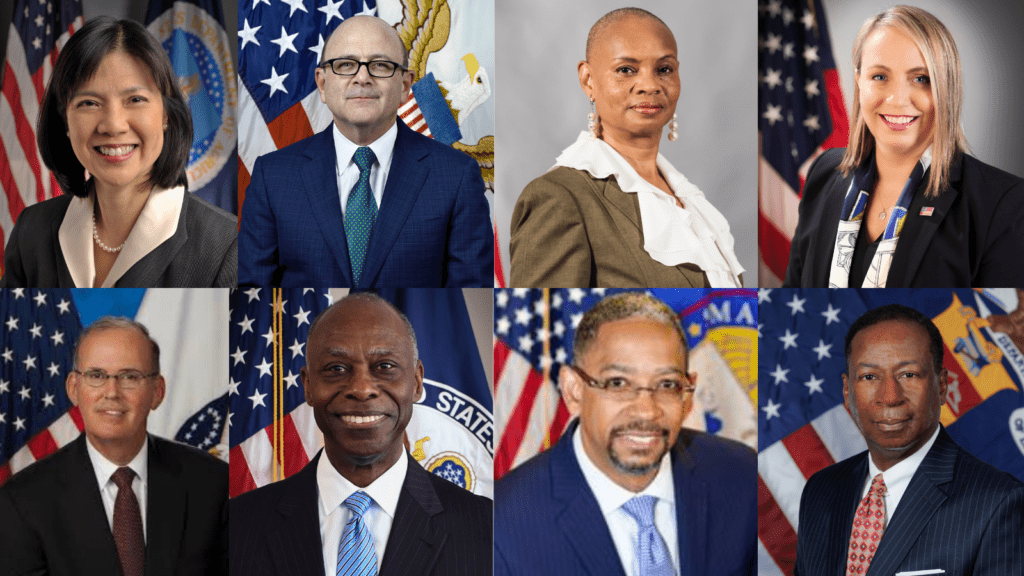

Profiles in Courage: Who Holds Power to Account? Inspectors General Challenge Trump’s Unlawful Dismissals

May 16, 2025

The Trump administration’s dramatic and bombastic foreign policy initiatives have gained considerable attention, whether with respect to the Ukraine-Russia conflict, the proposed US takeover of Gaza, Canada, Panama, and Greenland, let alone the tariffs “war.” Many of these initiatives have, to date, turned out to be vainglorious and are in the process of being challenged by reality.

By contrast, Trump’s interventions in Yemen are serious, and they have a daily impact on millions, even after the suspension of the bombing spree known as Operation Rough Rider. With the exception of particularly murderous strikes, the main attention they have received from the media came through the farcical “Signalgate” scandal.

Although Trump has now called off the strikes, without delivering on his promise to destroy the Huthis who rule over most of the country’s population, US policy is still exacerbating one of the world’s gravest humanitarian crises.

“Signalgate,” of course, refers to a Signal group of senior US officials discussing the details of planned air strikes on Yemen before they started on March 15. Thanks to national security advisor Mike Waltz, the editor of the Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg, was included in the chat, and the scandal thus became public. Indeed, it already has a Wikipedia entry!

The air strikes under discussion are one of three elements of the Trump strategy in Yemen, the other two being the redesignation of the Huthi movement — officially named Ansar Allah — as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO), and the immediate and complete termination of all US Agency for International Development (USAID) support for Yemen. Together these three elements are already having a devastating impact on the 35 million Yemenis.

US air strikes were a nightly occurrence until May 5, when Trump gave the order for them to be suspended. On April 29, the UK joined in, determined to prove itself a loyal lapdog to the Trump administration. In total, the US carried out more than 1,100 strikes. During the first month of the strikes, the death toll was comparatively low, with about 150 killed, most of whom were said to be military casualties.

However, in mid-April, the situation changed, with a far higher daily death toll, particularly among the civilian population. US bombing was nightly, using more powerful bombs and targeting far more locations than before. Some of the sites had been targeted since the beginning of the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen in March 2015, with the Saudi and Emirati air forces carrying out strikes until 2022 and the United States and the UK taking up the baton from early 2024.

The main areas under attack were the northern governorate of Saada, the original home of Ansar Allah and the place where its main leaders are believed to be, as well as the Red Sea ports: Hodeida is where the majority of Yemen’s desperately needed imports arrive, including fuel, wheat, and other staples. Sana’a and other urban areas were also hit, and the strikes spread fear and terror far and wide. Although most Yemeni construction is robust, Yemenis have not traditionally built underground shelters in anticipation of such a situation.

The most murderous attack was the bombing of Ras Isa port on April 17 which killed more than eighty people, the vast majority of them civilian employees of the port or transport companies. Another attack killed sixty-eight or more imprisoned East African migrants on April 28. Yemenis were being killed daily, and the civilian death toll exceeded five hundred, as powerful US munitions destroyed people’s homes and business facilities throughout the area under Ansar Allah control.

United States Central Command (CENTCOM) public relations gives us an indication of US military embarrassment at this situation. In 2024, it was prolific with announcements of US strikes, giving details almost daily, yet it has made very few statements since the new offensive began, notably breaking its silence in a bid to “justify” the April 17 strike on Ras Isa.

Although he initially boasted that he would “completely annihilate” the Huthis, later statements from Trump and other officials have claimed that the objective of the strikes was to restore “freedom of navigation” in the Red Sea. This was despite the fact that Ansar Allah had not targeted any ships during the Gaza cease-fire, and the US strikes started just before the Israelis broke the cease-fire agreement on March 18.

When Trump announced he was ending the strikes, he claimed that Ansar Allah had “capitulated” under US pressure: “The Houthis have announced to us that they don’t want to fight any more. They just don’t want to fight, and we will honour that, and we will stop the bombings.” At the same time, he also expressed admiration for their resilience: “You could say there was a lot of bravery there.”

Trump had several good reasons to end the strikes when he did. First, the Huthis had successfully downed seven MQ-9 drones, each of which costs $30 million, having already downed fifteen MQ-9s in the earlier period since November 2023. Their efforts also contributed to the loss of two F-18 fighter jets, worth $67 million each, which fell off a US aircraft carrier. During this confrontation with the United States, the Huthis were still able to successfully launch missiles against Israel, one of which reached Ben Gurion airport on May 4, wounding eight people and causing some damage.

There was also considerable opposition to the bombing from various senior US officials, whether because it was leading to the depletion of ordnance from the Pacific region, or because they believed Europe, not the United States, was the “main beneficiary” of access to the Suez Canal (an argument made by J. D. Vance in the Signalgate exchanges). Finally, Trump’s planned visit to the Gulf states supplied another reason for ending the strikes, since the Saudis did not want them to be in progress during the trip. Trump took the opportunity to claim victory, regardless of what the reality was, extricating himself from an operation that could have gone on forever without any visible achievements.

Trump did not mention “regime change” in Huthi-controlled areas as an objective, or even US support for Israel. From the start, Ansar Allah leaders have been clear that their actions are being taken in support of Palestine and against Israel. Huthi claims of victory sound less hollow than Trump’s: the downing of MQ-9s was especially significant, as their task is to identify “high-value” targets and without them, the US forces were bombing blindly. The seven weeks of bombing failed to kill any senior Huthi leader, although dozens of lower-ranking officers have been confirmed dead and there was massive destruction of infrastructure.

US lack of interest in solving the Yemeni crisis, whether under Joe Biden or Trump, is clear. Neither administration responded to the calls for military support from different faction leaders and vice presidents of the internationally recognized government (IRG) of Yemen, including Tareq Saleh, who have been asking for assistance to intensify the ground war against the Huthis for more than a year. The cease-fire announcement came as a bombshell for Israel but also for Yemen’s IRG, which was on the verge of sending another delegation to Washington to ask for military support against the Huthis.

In addition to direct military strikes on the Huthi-controlled areas, the other US policy changes toward Yemen since Trump came to power are further contributing to the dramatic worsening of living conditions in the country. Yemen lost its unenviable status as “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis,” not due to any improvements in Yemen itself but simply because at least two other crises have overtaken it in horror and inhumanity: the Gaza genocide and the Sudanese wars. Two-thirds of Yemenis are in need of humanitarian assistance, including seventeen million who are lacking food.

By May 15, the World Food Programme (WFP), the main provider of basic support for nutrition and food, had received only 12 percent of the funds it requires for this year. This total included absolutely nothing from the United States, which had provided 62 percent of its funds last year. The overall US contribution to the United Nations’ Humanitarian Response Plan for 2025 was $16 million, representing 6 percent of total funding.

With only 9 percent of its response plan financed to date, in desperation the UN published an addendum to its 2025 plan on May 13, urgently calling for $1.42 billion to prevent famine. The plan targeted assistance for 8.8 million people in Yemen, while pointing out that a total of 19.5 million need support. In his briefing to the UN Security Council on May 14, the head of the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) gave an indication of the gravity of the humanitarian crisis: there are 2.3 million malnourished children, only 69 percent of children are vaccinated, and Yemen alone accounted for a third of global cholera cases in 2024.

As Trump has ordered the termination of any funding for Yemen, as well as closed down USAID and transferred its residual functions to the State Department, no further US funding will reach Yemen during his administration. This comes at a time when other states are also reducing support while needs are increasing worldwide, so the implications are severe for the survival of Yemenis.

All development and humanitarian projects that the United States previously funded have stopped. In previous years, the US was the first- or second-largest funder in Yemen. Hunger and further deprivation will worsen over the coming months in Yemen, and indeed for millions of people in other countries where international humanitarian and development aid plays an important role in keeping people afloat.

The third element of the new US policy has been the redesignation of the Huthi movement as an FTO in the earliest days of the new administration. Far stronger than the designation by the Biden administration, this action will cause lasting difficulties. Although explicitly aimed at the Huthi movement, it will also impact Yemenis throughout the country, given the difficulties of identifying specific organizations.

Most banks, humanitarian organizations, and businesses of whatever size operate throughout the country. For partners outside of Yemen, it is simply much easier to cut relations with all Yemeni entities than to go through complex procedures to obtain permission to bypass the sanctions regime and prove that they are dealing with entities within the IRG-controlled area. This will affect importing companies for all basic necessities, whether food, medication, or other supplies.

Banking is one of the sectors most directly affected by the FTO. Following the designation, Sana’a based banks all agreed to move their headquarters to Aden, where the IRG’s Central Bank of Yemen is located. But this process is far from straightforward.

The International Bank of Yemen (IBY) is one of the two banks already sanctioned by the United States. It is Yemen’s largest commercial bank, and its inability to carry out international transactions will affect many small and medium businesses throughout the country who need to trade and communicate with the outside world. In addition to banking problems, the remaining productive industries will have further difficulties obtaining raw materials and exchanging data and other information with international partners.

The FTO and other financial constraints are particularly relevant for remittances. Such transfers are a major contributor to the daily survival of millions of Yemenis who have relatives and friends out of the country, people whose commitment to helping their families is deep.

While Yemenis can be found throughout the world, the majority are short-term residents in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Between them, these countries host about two million Yemenis. There are probably close to half a million Yemenis in Egypt, Jordan, and Turkey, many of whom are with their nuclear families.

Other than those leaving to escape the war, the overwhelming majority of Yemeni expatriates travel to earn an income to remit to their nuclear and extended families in Yemen. Some in the region can use informal networks and are less dependent on institutions subject to FTO sanctions, but most elsewhere will have serious difficulties sending funds to Yemen.

Beyond the immediate and medium-term impact of the renewed airborne destruction, further bad news looms. The Trump administration assumes that Ansar Allah takes its orders from Tehran and that its behavior in Yemen is an element of its policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran. The current Iran-US negotiations provide a hint of relief. But the Israeli strikes are at least as indiscriminate as the US ones and are likely to intensify so long as Ansar Allah continues to target Israel.

The restoration of freedom of navigation in the Red Sea is also doubtful in the short term. Egypt has lost $7 billion in Suez Canal revenues in 2024, but others, including ship fuel suppliers and insurance companies, are benefiting from the diversion around the Cape of Good Hope.

In an increasingly divided world, recent suggestions of Russian and Chinese support for Ansar Allah, whether they are based on reality or mere propaganda, bring Yemen into the new cold war, which threatens to become more active. The survival of millions of suffering Yemenis is simply irrelevant for administrations that share the interests and concerns of a few hundred billionaires and consider the rest of humanity dispensable, even disposable.

In this context, being one among the multiplicity of disasters in the world, mostly worsened by the Trump administration’s policies, Yemen has not received the media attention it deserves. Politicians in the self-styled international community focus on their perception of their own states’ interests and their alignment with the new Trumpian world order, ignoring the plight of Yemenis.

Great Job Helen Lackner & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.