Trump Exposes Own Idiocy With Comment About Looming Shortages

May 8, 2025

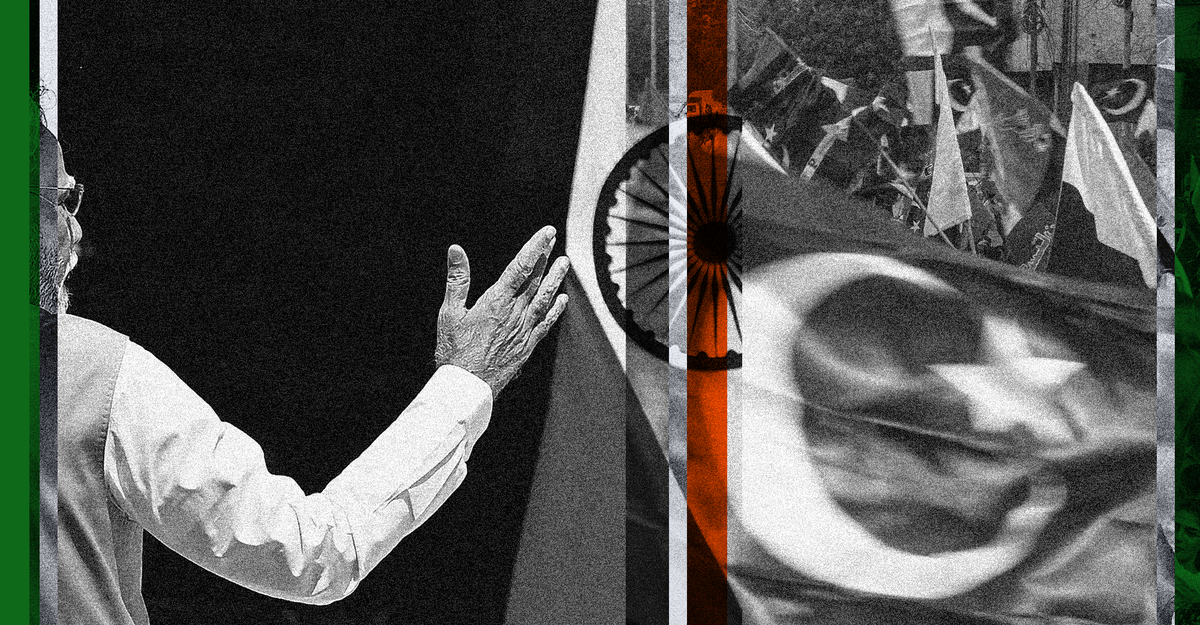

Why This India-Pakistan Conflict Is Different

May 8, 2025In Sinners, Ryan Coogler blends Southern horror, ancestral magic and feminist resistance to reckon with who gets to set the terms of value—spiritual, cultural and economic—in a haunted America.

This review contains spoilers.

“Numbers are always in a conversation.”

In Ryan Coogler’s Black Southern horror hit Sinners, the above quote is offered as sage advice to a young Black girl in the town of Clarksdale, Miss., by the gangster Smoke. Growing up among Black sharecroppers who are only ever paid with plantation scrips, which have no real currency beyond the plantations they work on—entrapping them in a system similar to chattel slavery—this young girl eagerly accepts Smoke’s offer of a dime to watch over his prized truck that he has just parked in town. (This is the Great Depression era circa 1932, so the value of “can you spare a dime?” makes sense here.)

However, Smoke—who, along with his identical twin Stack (both played to striking distinction by the same actor, Michael B. Jordan), have returned to the South with bags of cash stolen from the ill-gotten gains of both the Irish mob and Italian mafia back in Chicago—teaches her a lesson in bargaining. Our young pupil is quick to learn, as she ups her price to 50 cents, which Smoke then bargains down to 20.

We see this power of bargaining play out when Smoke then convinces the local grocers—the Chinese American couple Bo and Grace Chow (played by Yao and Lin Jun Li) who own stores on either side of the racial color line—to respectively provide supplies and create signs for his grand opening of a local juke joint he and Stack had just purchased from a saw mill owner (who is also secretly leading the local Ku Klux Klan). Grace deftly names her price while she and Smoke demonstrate numbers in conversation.

Grace is later shown dressed in her work clothes resembling the World War II-era symbol Rosie the Riveter. Between the young Black girl and this crucial reclamation of Asian women’s historical presence in the Mississippi Delta region, Coogler elevates his film toward feminist revision: a celebration and insistence on valuing the labor of women and girls who can name their price unapologetically, instead of taking them for granted.

Conjuring Black (Magic) Culture

Sinners is rightly recognized as a Black Southern gothic tale, with a plot driven by its male characters—significantly Miles Caton in his debut role as Sammie the Preacher Boy, son of a local pastor whose blues-playing guitar skills summon the ancient power of African griots, as well as attracts the evil spirits of vampires, the latter serving as the film’s villains.

Indeed, the film highlights the camaraderie and community of these men as sharecroppers working alongside their pregnant wives, or as wizened blues musicians who experienced and witnessed enough real-world evil to rival any vampirism.

This is brilliantly shown through the alcoholic Delta Slim character (poignantly portrayed by Delroy Lindo) who reminisces to Sammie and Stack about the lynching of his friend, following the passing of a chain gang, with whom Delta Slim demonstrates solidarity. The work song from the chain gang, combined with Delta Slim’s moaning and humming that comes at the tail end of his story, effortlessly conjures the blues music that drives the score and soundtrack of this film.

Yet, as historian Yvonne Chireau who was consulted on the film for cultural and historical accuracy of the Delta region, reminds us in a Teen Vogue interview: “Blues is the music of Hoodoo.” The creator of the website The Academic Hoodoo and author of the seminal work Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition, Chireau defines Hoodoo as an African American ancestral tradition, which is why she helped Cooger cinematically craft what she calls “Ancestral Time.”

If this ‘conjuring’ is visceral and emotive through the blues music, it is the blues woman and conjure woman who provides its intellectual heft.

The scene most audiences have already called historic and unprecedented captures this in one cinematic shot: Sammie’s powerful blues song “I Lied to You” opens up the portals across past, present and future, which summons spirits of precolonial African ancestors and the “unborn” of the future (the descendants, represented by our funk guitarists and hip-hop deejays and emcees, alongside our grinding, twerking and Alvin-Ailey-inspired dancers jamming alongside the juke joint patrons in 1932). The scene—heightened by the score that interpolates these difference musical sounds across time (including an ancient Chinese percussion sound to mark the presence of Grace and Bo at the juke joint)—is a cinematic feat and a beautiful amalgamation of African American history and its cross-cultural influences with those in proximity.

However, if this “conjuring” is visceral and emotive through the blues music, it is the blues woman and conjure woman who provides its intellectual heft.

Indeed, Annie (played by the naturally sexy, plus-sized Wunmi Mosaku) provides the voice-over narration that opens the film to describe the spirit-moving powers of musicians across different cultures: specifically, among the Irish, the Choctaw of the Delta region, and African Americans. It is her knowledge, specifically, that drives much of the resistance we see in the film. Annie is not only the first to identify the main villain, Remmick (played by Jack O’Connell in a memorable role) and his ilk as vampires instead of “haints,” as she first thought, but is also the one assembling all the necessary weapons to fight off the undead.

Blues Women, Conjure Feminists

In their definition of “Conjure Feminism,” Black feminist scholars Kinitra Brooks, Kameelah L. Martin and LaKisha Simmons state that Conjuring is as ancient as woman herself and, in the practice of Africana women, has been a Black feminist spiritual tool that protects, sustains and empowers. To be certain, the conjuring arts are not monopolized by the highly melanated or the feminine-gendered; but we argue that Black and female positionality informs a particular spiritual praxis that “can be shared—though its heritage, roots, survival and intimate possession belong to Black women alone.”

Annie provides this role in her instinct to “protect, sustain and empower,” even when determining the type of death she desires to save her from a life of damnation, which is what the undead represents for her. In many ways, her roots and herbs—which form the “mojo bag” she gives her partner Smoke as protection when he and Stack traveled (first as World War I soldiers, then as migrant workers turned gangsters in Chicago)—do the spiritual work that mirrors the military protection of Smoke’s gun (who towards the end of the film summons the rage of all those veterans lynched during the Red Summer and even those business owners massacred in Tulsa in 1921 in his revenge-killing of Klan members, the counterpoint villains to the vampires).

We see similar roles for the other main women in the film: Pearline (played by Jayme Lawson), the young married woman who lures Sammie with her dark-skinned beauty and who literally howls to the “Pale, Pale Moon” as a blues woman bringing the house down in another roof-burning number (howling, it is implied, because of the pleasure Sammie elicited from her during their time of intimacy).

Here, Pearline (who will later become the inspiration for Sammie’s band later in life) articulates the deep-seated pleasure of the crowd, while Mary (played by Hailee Steinfeld) who looks and passes for white but, due to her “one drop” blood inherited from her grandfather that makes her “Negro,” attempts protection and empowerment for this community.

In love with Stack, Mary wants to prove her loyalty when learning that the brothers need a profit, since most of the club’s patrons can only pay in the low currency of plantation scrips. Assuming the white banjo players (Remmick and his companions) have real money, Mary uses her whiteness to find out how their patronage will help with the juke joint’s profits.

Unfortunately, she becomes the first victim … and the first vampire villain allowed entry back into the club.

Is the Math “Mathing”?

If we go by Judeo-Christian binary thinking, it would be easy to think of the biblical moral here: “For the love of money is the root of all evil.”

And African Americans have enough cultural and historical memory to affirm this—from the profits that African chiefs and monarchs made when selling off captive Africans in the transatlantic slave trade (the Elmina slave dungeon in Ghana literally means “gold”), to the literal profits that came from selling our enslaved ancestors in chattel slavery to entrapping their descendants in sharecropping debt and bondage.

However, this brings us back to the “numbers in conversation.”

Again, here Annie challenges Smoke’s “blood money,” which to Smoke provides the only real “power” that matters on this material plane. However, Annie reminds him of the bargaining power of being in community with others—hence why she challenges him when he insists that the sharecropping patrons pay with “real” money and not scrips. Remmick the vampire shows off a gold coin that seems to be “real money,” but it too is not real, existing from a different time; it only looks real.

This is the illusion of whiteness as power, an illusion that costs Mary—straddling the color line through her actual bloodline—her life.

Somewhere, the soul has not been drained by whiteness. And not just any whiteness: a whiteness that refuses fellowship and camaraderie, instead seeking domination and erasure.

This again recalls the numbers game. If there is an equation Coogler seems fixated on, it’s the multiplication of two, or at least the binary structure of duality.

Coogler has mentioned the Smokestack twins represent the Ibeji twins of Yoruba lore, bringers of fortune—both good and bad. Indeed, the twins brought the duality of “freedom” that the juke joint represented along with the enslavement of vampirism, brought forth by the Irish vampire Remmick, himself a white colonized victim turned colonizing victimizer.

We especially hear and see it in the way his Irish song and jig “Rocky Road to Dublin” has dominated the hive mind of his recently turned vampires. The same juke joint patrons burning up the dancefloor through the blues have been drained of their “soul” both, literally and figuratively when they are reduced to mimicking Remmick’s cultural ballad and dance.

Even here, on the soundtrack, we hear the strains of blues and gospels screaming out toward the end of the song. Somewhere, the soul has not been drained by whiteness. And not just any whiteness: a whiteness that refuses fellowship and camaraderie, instead seeking domination and erasure.

Beyond Binary, Toward Diversity

This duality is constantly being challenged throughout the story and reminds us that the Delta region that gave us both the gospel and the blues and the racially restrictive categories of Black and white can also shift us beyond binary thought.

According to digital artist Tabita Rezaire, the Ifa divination of Yoruba culture—an ancestral foundation for Hoodoo—most likely influenced the binary coding that would evolve into our computer technologies, traveling from West Africa through Moors who brought ideas of divination to Spain, where the “logic machine” eventually influenced mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, who developed modern binary code. Drawing from this transnational history, Rezaire states:

We are praising our ancestors because also, what they provide for us is a divine record of consciousness. They are the divine internet… The analogy is that we are the computer.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs and Sangodare Julia Wallace similarly argue that we not only recognize this binary code beyond Westernization but to also transcend its binary limitations. As they posit, binary code “only works for zero and one. It does not work for two, three, four, or for most of us who do not conform.”

In sum, the work of blues and conjure requires transcendence and a “transformative intervention into value.”

This film is a triumph and righteous rebuke of our present era of anti-DEI policies and ideologies. May this way of thinking survive and thrive beyond the vampiric impulse to erase and dominate.

We see this with Coogler’s film and the choices he made, which certainly seem shaped by living in a multiracial America where his education as a millennial exposed him to the strengths of diversity, equity and inclusion. It’s why he and his Swedish college roommate Ludwig Göransson, the film’s music composer, could collaborate through cinema and music, and why his college girlfriend turned wife Zinzi Evans could purchase the necessary software for his screenwriting classes out of love when he was struggling financially.

It is this exposure and his redefined value for diversity that gave us the characters Grace and Bo with their daughter Lisa, who disrupt the racial binary by literally crossing the color lines of Mississippi in a cinematic shot that visually constructs Asians’ “racial triangulation,” or how Mary—despite her white appearance—can be called “family” by Annie in ways that disrupt racial segregation. (Or even how Mary and her true love Stack found ways to continue their taboo love through a taboo existence as the undead.)

It is why we get a cinematic “land acknowledgment” with the inclusion of Choctaw, the original inhabitants in the Delta Region, who have a brief appearance as vampire hunters.

Mostly, it is why we get two different renditions of the gospel song “This Little Light of Mine” as cinematic bookends: one version sung by a church choir of little Black children in all its innocence, the other as a post-credit performance by Sammie as a blues song expressing the real struggle of preserving that light. This reaffirms Sammie’s choice to continue with the blues, despite his father’s disapproval, in a move that disrupts the false Christian binary of good versus evil, sacred versus profane.

With the help of consultant Chireau and characters like Annie, Coogler captures the significance of conjure feminism that lights the way for our blues griots to open the portals and transcend duality. This film is a triumph and righteous rebuke of our present era of anti-DEI policies and ideologies. May this way of thinking survive and thrive beyond the vampiric impulse to erase and dominate.

Great Job Janell Hobson & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.