Fighting Side by Side in Israel-Palestine

April 1, 2025

Widespread firings start at federal health agencies including many in leadership

April 1, 2025

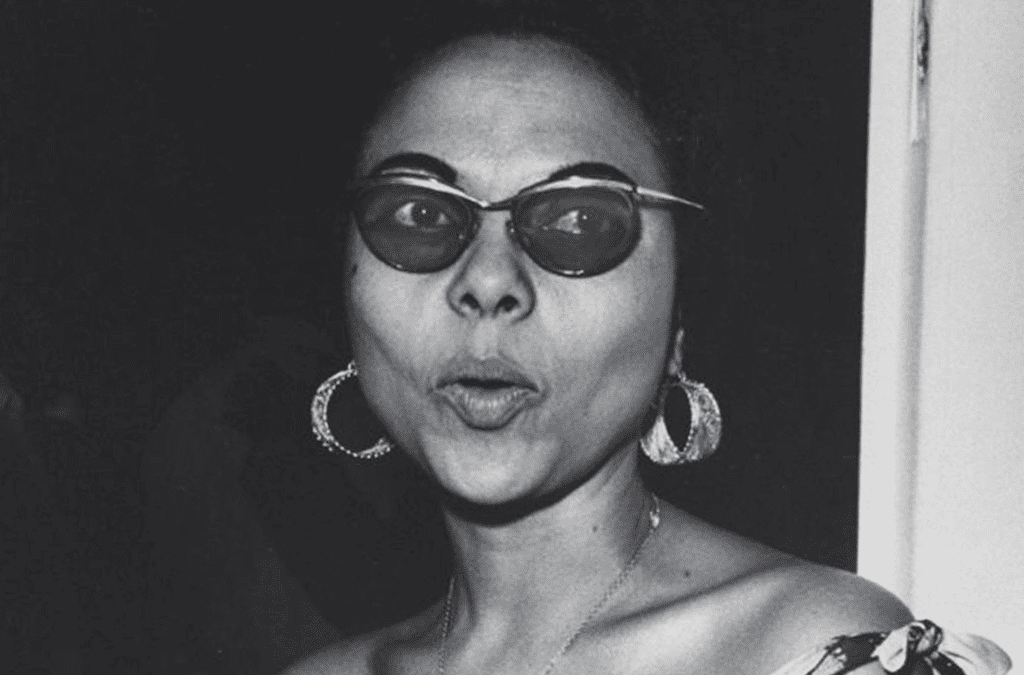

Andrée Blouin was one of the closest allies of Patrice Lumumba, the charismatic Congolese politician who led his country to independence before his murder in 1961. American and Belgian critics of the slain leader often held Blouin in contempt. To them she was a “fanatic,” possibly a communist agent, certainly strongly opposed to Western power. Almost forty years since her death in 1986, aged just sixty-four, Andrée has drifted somewhat into obscurity.

The recent reissue of her long out-of-print autobiography, My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, provides evidence of her enduring importance. It comes at a time of renewed interest in the politics of Central Africa. The 2024 award-winning documentary film by Johan Grimonprez about American jazz music’s uncomfortable relationship with empire, Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, quotes her extensively. This renewed attention is overdue. Her life story is a remarkable tale of personal and political struggle by a truly extraordinary individual.

As with many activists, Andrée’s engagement was shaped by firsthand experiences. The late colonial era, when the continent’s subject peoples were starting to mobilize on a grand scale to throw off foreign domination, was the backdrop to her life. So much seemed possible. Yet optimism often ended in disappointment. The continent’s more conservative leaders saw sovereignty mainly as a replacement of European faces with African ones, leaving intact existing borders and social relations fostered by colonialism.

Blouin chose instead to side with the interests of ordinary people and viewed political struggle in Pan-Africanist, rather than nationalist, terms. Her “country” did not have one flag, but many.

Andrée was born on December 16, 1921. Her father was a French businessman, and her mother the fourteen-year-old daughter of a Banziri chief in the French colony of Oubangui-Chari, today’s Central African Republic. Aged barely three, Blouin was sent off to a Catholic orphanage in Brazzaville, capital of the small French-ruled Congo, across the river from the much larger Belgian colony of the same name.

The orphanage in which she spent her early life was created for unwanted mixed-race girls guilty of the “sin” of having been born of European and African liaisons. It was, as Andrée put it in her later years, “a kind of waste bin for the waste products of this black-and-white society. . . .” The orphanage’s nuns, she recalled, were especially severe. They fed the girls sparingly and punished them for the slightest infraction. Blouin quickly developed a reputation as a troublemaker.

At seventeen, Andrée and two friends escaped by scaling the orphanage’s walls. For her, there were too many new sights, sounds, and customs outside of these walls to stay put. In My Country, Africa, Andrée writes that she “watched with the ardent eyes of one who had been deprived of her Africa for fourteen years.”

In the years that followed, she lived in different French and Belgian colonies, worked as a seamstress, managed a transport enterprise and a plantation (with a hundred employees), ran her own parcel delivery business, and wrote prize-winning poetry.

Far from the clutches of the orphanage’s nuns, who planned early marriages between Andrée and other mixed-race orphans, she was free to pursue her own relationships. The first two were with European men, “of the race that had so often hurt me.” Both unions eventually soured, but gave her two children, a daughter and a son. When her son, at two, became seriously ill with malaria, she tried to obtain quinine to treat it. But the French authorities reserved the medicine for “whites only.” Her son died, a tragedy that, she wrote in her memoir, “politicized me like nothing else could.”

In 1948, Andrée would meet a former French artillery officer and mining expert named André Blouin. The couple would marry four years later, stay together for a quarter century, and have two children. Unlike many other white men in Africa, André “had escaped the colonialist mentality,” she wrote.

The couple moved to Guinea in West Africa after André got a job researching alluvial gold mining in the country. The 1950s were a feverish political time across Africa, and André supported his wife’s activity throughout it. In Guinea, the strongest nationalist party was the local branch of the regional Rassemblement démocratique africain (RDA). It was led by Ahmed Sékou Touré, a fiery trade union leader. Andrée saw her own developing views crystalized by Touré’s determination to achieve genuine independence from colonial rule. His enthusiasm had, she wrote, given her a “second birth.”

The most pressing issue for the RDA was a referendum called by French president Charles de Gaulle in which voters in the colonies would choose whether or not to belong to a new French “Community,” which would retain military, diplomatic, and economic ties to the metropole. Touré’s RDA saw this as a maneuver to perpetuate French domination and called for a “no” vote. Andrée eagerly jumped into the fray, traveling hundreds of kilometers with RDA activists. Twice, she and several companions were almost killed in mysterious road “accidents.” Officials soon ordered her expulsion and fired her husband from his job.

By the time a majority of Guineans had voted “no” — making it the only one of France’s eighteen African colonies to do so — André and Andrée had fled the country. With Touré at the helm, the Blouins returned, he to work for the government and she to further promote Pan-African causes. Through Touré she met Ghana’s president Kwame Nkrumah and recorded a radio appeal to African women to champion continental unity in a broadcast that went out in both French and English.

Before returning to Guinea, Andrée had already engaged in several diplomatic initiatives of her own. She mediated a political rift between the presidents of the Central African Republic and Congo-Brazzaville, and another between clashing parties within Congo-Brazzaville. In the latter conflict, her intervention helped to end fighting that had claimed hundreds of lives.

The year 1960 was pivotal for Africa. Seventeen colonies won their independence. France, Britain, and Belgium had decided that maintaining formal rule was becoming too risky and began seeking new, less formal ways to retain economic and political influence. The ambiguities of that process were nowhere starker than in Congo, the vast, resource-rich territory that Belgians had pillaged for decades.

Although Andrée had previously spent some time in Congo, even learning a couple Congolese languages, her introduction to that country’s politics came by chance. One day, at a restaurant in the Guinean capital, she overheard several Congolese speaking Lingala and struck up a conversation with them in that language. One happened to be Pierre Mulele, a leader of the Parti Solidaire Africain (PSA), who was in Guinea hoping to secure Touré’s support. Soon, the head of the PSA, Antoine Gizenga, invited her to help mobilize Congolese women. With Touré’s blessing, she agreed.

In early 1960, Andrée spent months touring Kwilu and other Congolese provinces addressing rallies of thousands of women and men with a PSA caravan. She organized a pro-independence women’s association, which by the end of May had recruited 45,000 members. On the border with Portuguese-ruled Angola, she also helped establish a village of Angolan refugees, an early rear base for the rebel Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA).

The Belgian authorities sought to keep the Congolese fractured by playing on ethnic divisions and promoting more conservative currents against those aligned with Lumumba. They also bristled at Andrée’s influence, denigrating her for being a woman and a foreign communist agent. Despite Lumumba’s strong objections, they ordered her expulsion. On her way out of the country, Andrée took with her a protocol signed by a majority of Congolese parties. Her dissemination of that document to the international media helped undermine Belgium’s plan to bypass Lumumba by handing power to a moderate.

On June 30, 1960, with Lumumba as its prime minister, Congo gained formal independence. Listening to the radio in Guinea, Andrée heard his hard-hitting speech. The words were already familiar to her, since the speech Lumumba delivered — destined to stand as one of the most famous critiques of colonialism — was one she had helped to draft before her untimely departure. Ever discreet, she made no mention of that detail in her autobiography; her daughter Eve reports it in the epilogue to My Country, Africa, citing as evidence the testimony of a Congolese security officer.

At Lumumba’s request, Andrée returned to Congo, where she became his chief of protocol. But they had little time to build the newly independent state. Belgian politicians and businessmen continued to promote an array of factional splits and opponents, including a breakaway in the mineral-rich province of Katanga. America’s CIA recruited a young army colonel, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu (later Mobutu Sese Seko), who soon ousted Lumumba in a military coup. Andrée was again expelled.

For several months, chaos reigned. Mercenaries from Belgium, South Africa, and elsewhere flooded into Congo. United Nations peacekeepers were generally ineffective, but in some cases, they sabotaged nationalist efforts to retain control. Pro-Lumumba forces led by Gizenga attempted to rally opposition. As Lumumba tried to join them, he was captured, taken to Katanga, and murdered.

Andrée was in Switzerland in January 1961 when she learned of Lumumba’s death. To journalists who confronted her and asked for comment, she said that “all the hot words, the passionate outpourings that had been the substance of my days for so long, had been drained from me in this loss. I was unable to speak.”

Steeled by a lifetime of difficulties and disappointments, Andrée eventually bounced back. In 1962, after the victory of Algeria’s independence war against France, she and her family moved to Algiers. For at least the next decade, the Algerian capital served as a “Mecca” for revolutionaries worldwide, as Guinea-Bissau’s legendary guerrilla leader Amílcar Cabral put it.

Andrée wrote regularly for El Moudjahid, the newspaper of Algeria’s National Liberation Front. Algerian president Ahmed Ben Bella asked her to oversee humanitarian relief for orphans of the Congolese struggle. She championed the massive rebellion of “Lumumbist” rebels that shook eastern Congo in the early and mid-1960s, led in Kwilu by her old friend Mulele.

She was often visited by a diverse range of revolutionaries from South Africa, Mozambique, Angola, Eritrea, and other African fronts, even Palestinians and American Black Panthers. Her living room, she quipped, was “the chancellery of the United States of Africa.”

After moving to Paris, where she would die of cancer in 1986, she continued to write essays and books throughout the 1970s and 1980s, including her autobiography, which was first published in 1983 but was out of print before Verso Books reissued the book this year. According to her daughter Eve Blouin, Andrée remained convinced to the end that Pan-African revolution would eventually overcome all the neocolonial intrigues and that “the future belonged to the unity of free, sovereign peoples.”

Almost forty years on from her death, the value of Andrée’s work remains in its sober assessments of the prospects and aims of many prominent African leaders, the heart-wrenching descriptions of human sufferings, and the sharp dissections of colonialism’s many injustices and absurdities.

Great Job Ernest Harsch & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.