Latino Voters Who Defected to Trump Are Beyond Pissed at Him

May 16, 2025

Charlie Kirk: “I was just texting with the White House staff today. … I want to get my marching orders, and they were really quick to respond.”

May 16, 2025When Donald Trump fired the head of the Copyright Office, Shira Perlmutter—a move he arguably does not have the power to make, given that the office falls under the jurisdiction of the Library of Congress, which is by law and tradition overseen by the legislature and not the executive—I kind of assumed that this was a move organized by the White House’s tech bros. A few news reports suggested when all this went down that the intention might be to neuter the Copyright Office’s ability to restrict AI companies from using and abusing copyrighted materials for their own benefit.

If the pro-AI crowd did organize this defenestration, the Verge is reporting that it backfired: Apparently, Perlmutter’s replacement is from a wing of the MAGA movement that is at best ambivalent about the tech bros.

All of this is worth keeping an eye on for multiple reasons (not least among them being, you know, the potential violation of the separation of powers). But I just want to take a moment to highlight the actual report from the Copyright Office that may have sparked all this, because I think it’s an incredibly important document for those of us who worry about the AI-obsessed billionaires who think they should be allowed to steal whatever copyrighted artwork they need to power their suicide-recommendation engines.

Some background: For large language models to be any good at mimicking human conversation, they first need to be fed enormous quantities of conversational data. For reasons that should be fairly obvious, movies and novels often have enormous quantities of conversational data, making them very valuable for this purpose. (For more on the technical side of this, you could listen to my interview with Alex Reisner, who has tracked which movies and TV shows are illicitly being fed to the LLMs.)

Long story short, in order to train programs like ChatGPT and some of its competitors, copyrighted material was used. No one really denies this. The question was whether or not that training fell under the rubric of fair use—a legal carveout that, in certain circumstances, lets copyrighted material be used without first getting the copyright owner’s permission. Artificial intelligence executives defended force-feeding an LLM millions of pages of scripts by comparing it to a novice screenwriter reading, say, William Goldman’s Marathon Manscreenplay. How do screenwriters learn to write? They read screenplays! This is no different, just on a larger scale.

Of course, it is different and this specious line of reasoning fooled roughly no one. The question is the degree of difference and whether or not it runs afoul of fair use. There’s a four-part test to determine whether or not something falls under fair use, including the nature of the copyrighted work in question, the amount of the work being used, how it is being used (e.g., for profit or for education?), and the effect on the market for the already-copyrighted work.

So whether or not something counts as fair use is a complicated question, more art than science—and in the case of the large language models, the answer to that question has enormous financial consequences. The tech magnates have said that licensing the material they want to use to train their LLMs would be prohibitively expensive, so they would prefer simply to steal it, thanks. To this the Copyright Office has, apparently, said Uh, not so fast guys.

“When a model is deployed for purposes such as analysis or research—the types of uses that are critical to international competitiveness—the outputs are unlikely to substitute for expressive works used in training,” the Copyright Office report concludes. “But making commercial use of vast troves of copyrighted works to produce expressive content that competes with them in existing markets, especially where this is accomplished through illegal access, goes beyond established fair use boundaries.”

We’ll see how this shakes out through the courts. But this is a good first step to ensuring that the creators of AI have to, at the very least, compensate the people they’ve ripped off these last few years.

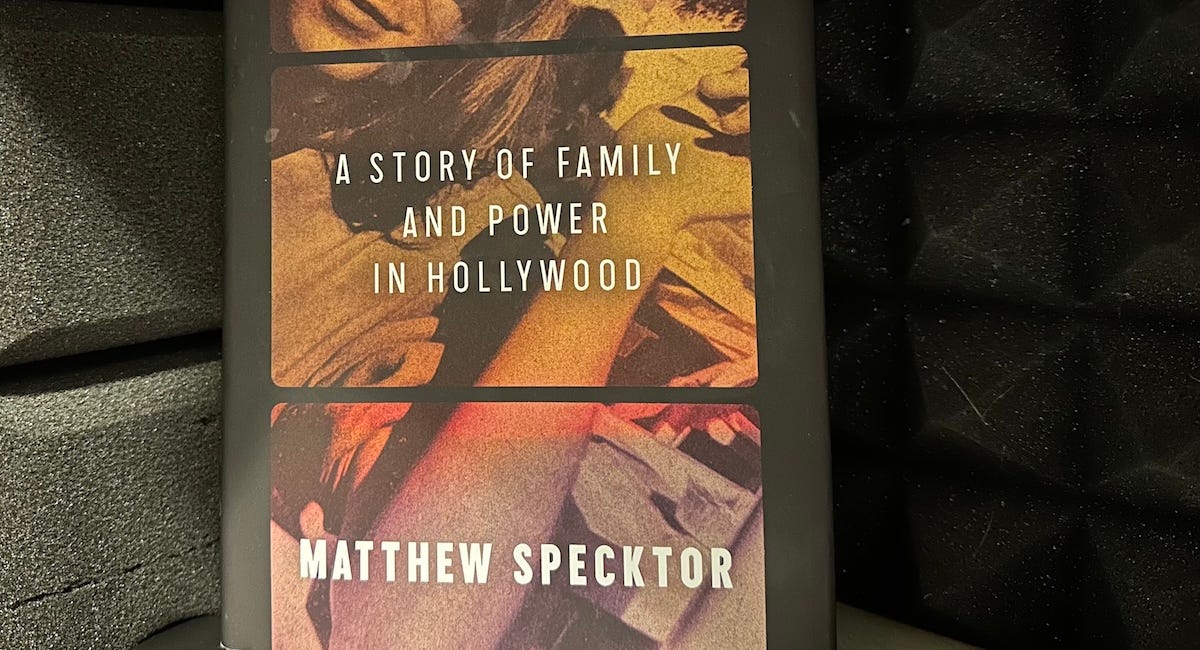

On this week’s Bulwark Goes to Hollywood, I interviewed Matthew Specktor about his new book, Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood. Part memoir, part historical novel, and entirely about the evolution of Hollywood as it grew from a dream factory into an Armani-suited shark tank, Matthew’s book is a really fascinating and compulsively readable ground-eye view of a changing industry.

Bulwark Goes to Hollywood

One Family’s Journey Through Hollywood

I’m joined by Matthew Specktor, author of The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood. Part novel, part memoir, and entirely entertaining, Matthew’s book is a revealing look at life in Hollywood when you’re not on the A-list but occasionally adjacent to it. In addition to relating the drama that makes any family intriguing, Matthew’s book …

You ever know a guy who just makes a face and it cracks you up? The sort of guy who, with the arch of an eyebrow or a hunch of the shoulders or an out-of-place squint, just sends you into gales of laughter?

Tim Robinson is one such guy, as evidenced both by my own reactions to the opening moments of Friendship and the reactions of the rest of the audience. After a brief prelude in which he and his wife discuss their feelings about her recovering from cancer—not a natural spot for comedic work!—he shows up on the screen ensconced in an oversized winter coat, struggling with a cup of coffee, grimacing at his predicament, and folks just started laughing. It’s not quite physical comedy, though the way Robinson moves is just awkward enough to be funny. There’s no real “joke” here in a setup-punchline sort of way: he’s just trying not to spill his drink.

And yet: waves of laughter. Tim Robinson, both here and in his cult hit sketch show I Think You Should Leave, is the current human embodiment of the type we might think of as American Goober. Kind of clueless, extremely awkward, and unaware of how to behave in virtually any social setting, the American Goober is rarely mean-spirited, but he tries the patience of those with whom he comes in contact. Mainstream iterations of the American Goober over the years have included various characters on the Andy Griffith Show (including one literally named Goober), Bob Denver’s Gilligan, and Jim Varney’s Earnest; Adam Sandler built a whole career out of this type, from Barry Egan in Punch-Drunk Love to, more recently, Hubie of Hubie’s Halloween.

Tim Robinson’s Craig is on the darker edge of this spectrum. He works for a company that designs mobile apps in the hopes of making them “habit forming”—that is, addictive—and seems pretty good at his job, if a bit lonely. A victim of the atomization of modern suburban ennui? Well … no. Everyone else in this community seems to have a friend group. We quickly come to realize that Craig is, frankly, kind of a weirdo. He just doesn’t know how to fit in, he lacks the social conditioning most of us pick up through everyday interactions and social clues. Which is why he’s so struck by the surprise friendship with new neighbor, Austin Carmichael (Paul Rudd), a local weatherman who also happens to be in a band.

Austin is, for lack of a better word, cool. Effortlessly cool. Charming and suave. (It helps that Rudd is, like Robinson, another one of those guys who can make you laugh with little more than a look and a twitch of the eyes.) And Austin finds something amusing about Craig. Again, not in a mean-spirited way, a look-at-the-loser sort of way. He’s just kind of easygoing and tickled by Craig’s foibles. Austin’s friends and wife are less amused, and when he tries to separate from Craig, things get … awkward.

Friendship has a melancholic core, given the subject matter: There’s something ineffably sad about friendlessness, even when the friendless individual is a goober like Craig. But Robinson’s particularly brilliant comedic insight is to make his characters incredibly off-putting without making them overtly cruel; we don’t hate them, but we also can’t quite empathize with them. His characters, including Craig, often come off like a maladjusted, less successful version of Larry David (or “Larry David” as seen on Curb Your Enthusiasm), which heightens the “cringe” part of Robinson’s brand of cringe-comedy to near-unbearable levels.

It’s a variety of precisely demented genius I’ve never seen before, a gnarled, stubby branch of the Will Ferrell-Adam McKay comedy tree of the 2000s that included Anchorman, Step Brothers, and Talladega Nights. But McKay’s movies, even when focused on American Goobers, were, fundamentally, about guys you wanted to like. I don’t think we’re meant to like Craig. Pity him, perhaps. But also understand why he’s not the sort of dude you really want in your life, even casually. You see echoes of what Robinson does in the short-form work of guys like Conner O’Malley (who has a brief and hilarious part in Friendship), but I can’t think of anyone else working quite at Robinson’s level, particularly at feature length.

I’m honestly curious to see what mainstream audiences make of this movie. Me? I laughed out loud a dozen times, and these weren’t amused chuckles; they were unexpected, surprising-even-to-me barks. It’s the funniest feel-bad comedy of the year.

Great Job Sonny Bunch & the Team @ The Bulwark Source link for sharing this story.