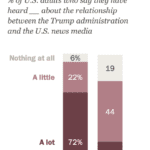

Far fewer Americans are hearing about Trump’s attacks on the media this time around, report finds

March 31, 2025

Charity-seekers from all over Pakistan flock to Karachi at Ramadan to collect alms

March 31, 2025ALTADENA, Calif. — Adonis Jones’ house was gone, but the keys were still in his hand.

For weeks after the fire, he carried them out of habit. They jingled in his pocket, and sometimes he twirled them between his fingers. And then, sitting in his car one evening after making the two-hour drive from Los Angeles to Fontana, where he was crashing at his ex-brother-in-law’s home, reality hit.

“I don’t even got no locks,” the 67-year-old remembers saying out loud to himself.

There, he decided it was time to slide those keys off the ring, one by one. His pocket felt lighter. The grief did not.

His family is one of many Black families in California navigating the long and uneven road of disaster recovery, where aid is slow and support often falls short. After the Eaton Fire ripped through Altadena, taking 17 lives and more than and 9,000 structures with it, nearly half of the city’s Black residents saw their homes reduced to rubble. It devastated a historically Black neighborhood that had endured generations of discrimination and, in recent years, the pressures of gentrification.

But the real battle starts afterward. Residents told Capital B they’re left scrambling for housing in an increasingly unaffordable market, navigating endless paperwork, and coping with the emotional toll of displacement. For Black families, disasters often mean less aid and longer instability. There are months that melt into years of couch-surfing, the slow burn of losing relationships when your loved ones can’t offer the support you need, and the everyday stress that quietly reshapes what it even means to have a home.

A lifetime of coaching had taught Jones to stay calm under pressure, to adjust when the game changed. But no playbook could prepare him for the reality that the Eaton Fire’s destruction wasn’t confined to the furniture or the family photos that were incinerated along with his home of 55 years. It was in the way Denise, his wife, carried her pain. It was in the small reminders that crept up unexpectedly.

It came at the grocery store when he saw someone wearing a familiar hoodie. Did I have that exact one? He wondered. He couldn’t remember.

“That’s the crazy part,” he said. “You think you’d know everything you lost that meant something to you, but then you start seeing other people with stuff that you might have had, and it hits you like a brick all over again.”

It is in those kinds of instances where it becomes clear that recovery isn’t only about rebuilding, he said. It is about acknowledging the life and routine that has been ripped away and the slow process of figuring out how to bear it.

Jones knows he and Denise were lucky to find a place quickly, but it was harder for her — she didn’t know the people they were staying with. She became quieter, withdrawing into herself in the aftermath, he said. And staying in more industrial, working-class Fontana, where big rigs rumbled down the street, was a stark shift from their quieter suburban community.

After disasters, studies show that Black communities often face higher rates of mental health issues such as post-tramatic stress disorder and depression compared to white communities. For Black disaster survivors, this stress can shorten lives. Researchers have linked this instability to higher death rates, underscoring the long shadow these disasters cast.

“Everyone will eventually experience their [Hurricane] Katrina moment,” he said, alluding to how severe weather and climate change have converged to make virtually every pocket of the country susceptible to catastrophes. By century’s end, environmental threats will displace more people in the U.S. than the Great Migration, uprooting millions nationwide. He said how we respond as individuals and as a people will be the real question, rather than if we can escape the wrath.

That is why, he and his daughter Rochele said, it is essential to find joy and peace in unexpected places. This allows you to move forward, even when the past keeps showing up in ways you’d never expect.

“There’s some good days and bad days,” Rochele, who is 42, explained. “I try to stick around, to scream the joy, and to remind [Adonis and Denise] that there are moments to enjoy, be thankful and grateful for every morning.”

After disasters, this is what recovery looks like

On a cold, wet Saturday afternoon, two months after losing their house, the Jones family gathered with loved ones for lunch. They’d just signed the papers for a new rental in Monrovia, a short drive from the blackened skeletons of Altadena. Salsa bowls splashed color onto the table as glasses clinked and laughter cut through any quiet heaviness.

“We all feel so loved,” Rochele said, and she saw it in everyone’s faces, including her father, who she said is not the kind of person to ask for help. It meant something more that it was coming from people who “left their homes behind, too.”

With wildfires doubling in intensity over the past two decades, there will be a lot more people out of their homes. And the communities hit hardest by the fires, and the droughts and extreme heat fueling them, are often the ones with the fewest resources to recover. Across the country, Black neighborhoods face the trifecta of being more likely to live in areas prone to flooding, heatwaves, and fires, but are also much more likely to be underinsured (not having enough coverage when it counts) or not insured at all.

Because of this onslaught, on average, after disasters, the wealth of Black households decreases by an average of $27,000 while white households see their wealth increase by $126,000, whether through aid from the federal government or private insurance. And sometimes interpersonal racism plays a role: Studies show that Black homeowners often watch neighbors receive federal assistance while their own applications are denied, even when the damage is identical.

Jones wonders if similar patterns are emerging after California’s wildfires, as he’s seen his neighborhood turn to potlucks, GoFundMe campaigns, and neighbor-to-neighbor support to recover. He’s also watched his friends cry on TV and social media to rake in that support, and he wonders if his inability to sell his trauma might make it harder for him to financially recover.

“Some of the people who helped, I never even met before,” he explained, “and some who I expected to be there … weren’t.”

Because of this lack of aid, Black families experience longer periods of displacement, leading to even more hardship. In New Orleans, more than a third of Black residents never returned after Hurricane Katrina, not because they didn’t want to, but because they couldn’t afford to. This kind of loss reshapes entire cities, accelerating the erasure of Black neighborhoods and cultural hubs under the guise of “rebuilding.” Signs point to it also happening in Los Angeles, where rental hikes have run twice as high as the national average since the fires.

Jones said he doesn’t know where most of his neighbors have been able to relocate, especially those who were already renters. The loss of passing interactions, waves, and seeing familiar faces contributes to the larger feelings of deprivation.

Past Coverage:

“This place is special. Everyone knows everyone somehow, and we’re all connected — so rooted in love and respect,” explained Marcus Betts, another resident who lost a family home of 50 years.

Betts, like the Jones family, wants to rebuild as quickly as possible, but “it’s a balancing act,” he said. “We don’t want the rebuilding process to feel like more trauma, but we also don’t want it to be easy for developers to come in and take away the soul of this place.”

Already, the distinctive features that defined Altadena’s landscape — the open fields and winding trails where Black cowboys rode proudly for generations — have become barren stretches cloaked in ash, their familiar rhythms silenced and their paths emptied of hoofbeats. After disasters, the focus tends to be placed on the built environment like the businesses and homes lost, so regrowing the landscape, tending to green spaces, and replanting trees and native plants usually happens at the very end of the process, if at all.

The Jones family knows they can’t get back everything that perished, but they’ve discovered that happiness and grief often live side by side. Jones recalled the day he bought a new set of golf clubs after his old ones melted in the inferno. At first, the purchase felt extravagant, especially when so many urgent needs remained, but after weeks of draining commutes and uncomfortable nights far from home, he craved something familiar. He learned that he might have to reframe what he views as necessities and needs after the fire. Now, he’s back on the green at least once a week, reconnecting with what makes life feel normal again.

And so, they find joy where they can. A long lunch with family, a walk around the block, or bingeing a TV show in their new rental home. The locks may be different now, but the love inside is just as strong.

“We laugh because we have to,” Rochele said.

And because somehow, even through all this, they still have each other.

Great Job Adam Mahoney & the Team @ Capital B News Source link for sharing this story.