In Uncertain Times, We Cannot Stay Silent

April 7, 2025

Remembering Amadou Bagayoko, Half of Malian Band Amadou & Mariam; Watch 2018 Interview & Performance

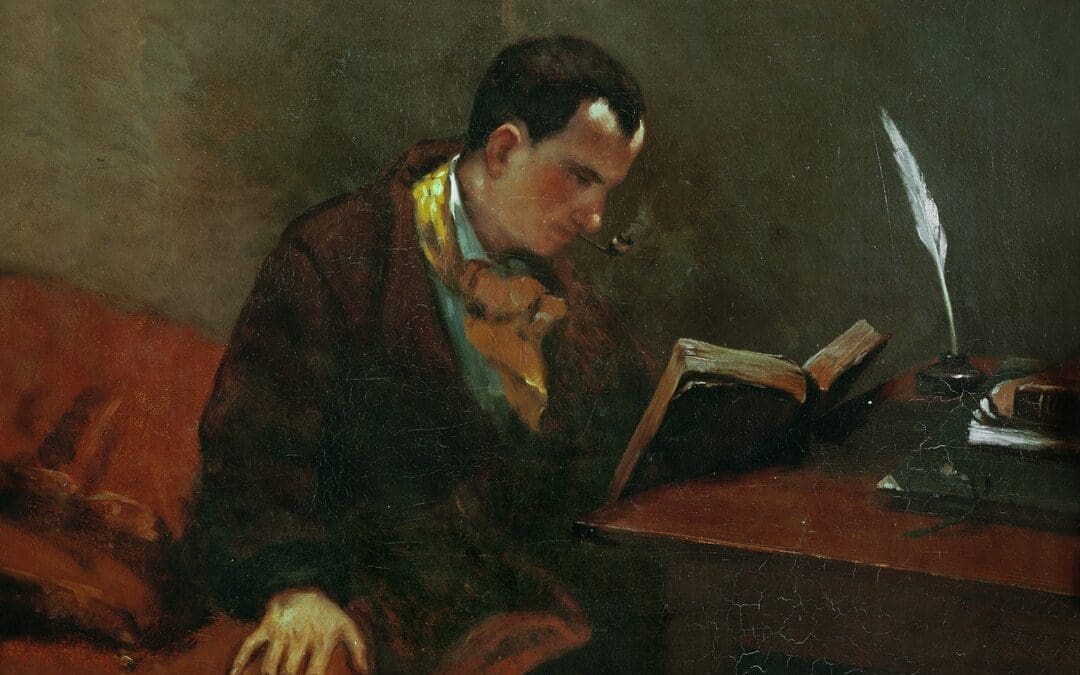

April 7, 2025Despite being born more than two hundred years ago, Charles Baudelaire’s poetry retains the feeling of something contemporary. In Verso Books’ new dual-language edition of The Flowers of Evil (Les Fleurs du mal), translated economically by Nathan Brown, the poet’s contradictory, shape-shifting, and still-startling voice emerges afresh. This is how Brown translates a quatrain from “The Sun” in which Baudelaire likens the poet’s vocation to a sword fight with his own imagination:

I practice my fantastic fencing as I go,

Sniffing every corner for the chance of rhyme,

Stumbling over words like paving stones,

Bumping into lines dreamed long ago.

For Baudelaire, beauty must be fought for. Or as he put it, “The study of the Beautiful is a duel in which the artist cries out with fear before he is vanquished.” This image of the poet as someone at war with the world was one Baudelaire cultivated. He helped to pioneer the modern image of the poètes maudits, or tortured poet, and inaugurated the definitively “modern” project of art as the last refuge of the heroic scoundrel, the ostracized outcast, the individual in search of relief or redemption from the evil and banality of modern life.

Baudelaire was born in 1821 to a prosperous family in Paris. His father died when he was just five, and his mother soon remarried to General Jacques Aupick, a man who would rise through the ranks of France’s military bureaucracy during and then after the Second Republic. Baudelaire, meanwhile, lived a life in artistic exile — although he escaped his stepfather’s attempts to send him into actual exile in Calcutta by sneaking onto a boat back to Paris. Not unjustly, he compared himself to Hamlet, although he offered a modern spin on the Shakespearean hero. What motivated Baudelaire was the lifelong self-hatred of a man unable to move beyond his own bourgeois upbringing.

After his father died, Baudelaire was due a significant inheritance. But on reaching maturity, he proceeded to squander it — on paintings, wine, dandyish clothes, and prostitutes — at such a pace that his allowance was frozen and placed under the humiliating control of a lawyer. Baudelaire, consequently, would struggle for twenty years as a jobbing writer and art critic, begging for money from his family or cobbling together cash as a hack for this or that publication. All the while — as his irregular, tormented, and intoxicated hours allowed — he was putting together a body of poetry.

The Paris of the mid-nineteenth century was one dramatically in flux. The entire city was undergoing perhaps the most rapid and drastic modernizing “urban renewal” of any major European capital in history within a comparative span of time. At Napoleon III’s behest, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann was demolishing and rebuilding medieval Paris through the 1850s and ’60s, Baudelaire’s most productive years.

Slums, cafes, and theaters were demolished; whole neighborhoods were expropriated by the government and passed into wealthier hands; narrow, mazy medieval streets razed and replaced by the huge boulevards which had a second purposes as avenues for military maneuvers (the streets of Paris would prove their efficacy for this purposes two decades later when troops would violently suppress the Paris Commune in 1871). As Walter Benjamin acutely observed, here and for the first time “along with the growth of the big cities there developed the means of razing them to the ground.”

Baudelaire was watching entire communities and histories disappear before his eyes. At the same time, just like in London, industrial and colonial ripples were finding their way to the metropole. In his introduction, Brown looks closely at one of Baudelaire’s most-celebrated poems, “The Swan.” He finds a miraculously condensed locus of these chaotically converging forces. The speaker wanders through some strange “new Carrousel” of Paris, “this camp of stalls” and “confused bric-a-brac” early one morning as “cold and clear work awakens.” Into the swirl, Baudelaire throws a heartrending image, noticing “a swan that had escaped its cage,” confused, thirsty, dragging itself around, “webbed feet scraping dry stones” and seeming to utter “reproaches to God.”

Later “before the Louvre,” the speaker is “oppressed by an image” — the swan has been transfigured in his imagination. At first, she reminds him of “exiles, ridiculous and sublime”; then,Andromache, the wife, then widow, of the Trojan hero Hector, who was reduced to “lowly chattel” after the defeat of her city, engulfed in the “immense majesty of your widow’s grief.” Then abruptly: “I think of the negress, gaunt and consumptive . . . seeking, eyes haggard / The absent palms of splendid Africa / Behind the immense barrier of fog.”

Swan becomes Andromache, who becomes a consumptive African woman displaced amid the squalor of the colonial metropole, which in turn becomes a vision of all “the captives, of the vanquished! . . . and of many, many more!” The final, desperate exhortation to all the “many more” is an admission of impossibility, the impossibility of recalling, within “the forest of my mind’s exile,” those countless disregarded ones, both the “captives” and the “exiles” of the modern imperial project, which carelessly crushes them through the force of “progress.”

Progress, what Baudelaire called “paganism for imbeciles” and “a doctrine of idlers and Belgians,” was the enemy. He was not convinced that “the primeval perversity of man” was going to be corrected by officially enforced optimism: “Civilized man invents the philosophy of progress to console himself for his abdication and decline.” It is difficult to not feel the attraction of Baudelaire’s pessimism:

The Paris of old is no more (the form of a city

Changes more swiftly, alas! than a mortal heart).

Misery for him was perhaps a kind of survival strategy of the soul. Following the publication of the first edition of Flowers in 1857, Baudelaire was prosecuted for “offense to public decency.” For the crime of publishing poems with names like “The Litanies of Satan,” censors accused him of promoting anti-religious sentiments. Baudelaire wrote to the secretary of state: “I do not feel guilty at all. I am, on the contrary, very proud of having written a book that inspires only fear and horror of evil.” To another correspondent, he called Les Fleurs a book of “ardent and eloquent spirituality.”

In an essay on Baudelaire published in 1930, Anglo-Catholic conservative poet T. S. Eliot applauded his lifelong, defiant courage:

Damnation itself is an immediate form of salvation — of salvation from the ennui of modern life, because it at last gives some significance to living. . . . So far as we do evil or good, we are human; and it is better, in a paradoxical way, to do evil than to do nothing: at least, we exist.

Baudelaire struggled, until his death from a lingering case of syphilis aged forty-six, to at least be human, and to prove in poetry that such a thing was still possible. He succeeded, in Victor Hugo’s words, in producing “a new shiver.” We must hope ourselves still capable of following his example.

Great Job Gus Mitchell & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.