Inside the spectacular rise and crash of India’s largest EV company

April 30, 2025

“He Was Pissed”: Trump’s Vile New Tariff Threats Take Unnerving Turn

April 30, 2025Something strange, and potentially alarming, is happening to the job market for young, educated workers.

According to the New York Federal Reserve, labor conditions for recent college graduates have “deteriorated noticeably” in the past few months, and the unemployment rate now stands at an unusually high 5.8 percent. Even newly minted M.B.A.s from elite programs are struggling to find work. Meanwhile, law-school applications are surging—an ominous echo of when young people used graduate school to bunker down during the great financial crisis.

What’s going on? I see three plausible explanations, and each might be a little bit true.

The first theory is that the labor market for young people never fully recovered from the coronavirus pandemic—or even, arguably, from the Great Recession. “Young people are having a harder time finding a job than they used to, and it’s been going on for a while, at least 10 years,” David Deming, an economist at Harvard, told me. The Great Recession led not only to mass layoffs but also to hiring freezes at many employers, and caused particular hardships for young people. After unemployment peaked in 2009, the labor market took time to heal, improving slowly until the pandemic shattered that progress. And just when a tech boom seemed around the corner, inflation roared back, leading the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and cool demand across the economy. White-collar industries—especially technology—were among the hardest hit. The number of job openings in software development and IT operations plunged. The share of jobs posted on Indeed in software programming has declined by more than 50 percent since 2022. For new grads hoping to start a career in tech, consulting, or finance, the market simply isn’t that strong.

A second theory points to a deeper, more structural shift: College doesn’t confer the same labor advantages that it did 15 years ago. According to research by the San Francisco Federal Reserve, 2010 marked a turning point, when the lifetime-earnings gap between college grads and high-school graduates stopped widening. At the same time, the share of online job postings seeking workers with a college degree has declined.

To be clear: College still pays off, on average. The college wage premium was never going to rise forever, and the fact that non-college workers have done a little better since 2010 isn’t bad news; it’s actually great news for less educated workers. But the upshot is a labor market where the return on investment for college is more uncertain.

The third theory is that the relatively weak labor market for college grads could be an early sign that artificial intelligence is starting to transform the economy.

“When you think from first principles about what generative AI can do, and what jobs it can replace, it’s the kind of things that young college grads have done” in white-collar firms, Deming told me. “They read and synthesize information and data. They produce reports and presentations.”

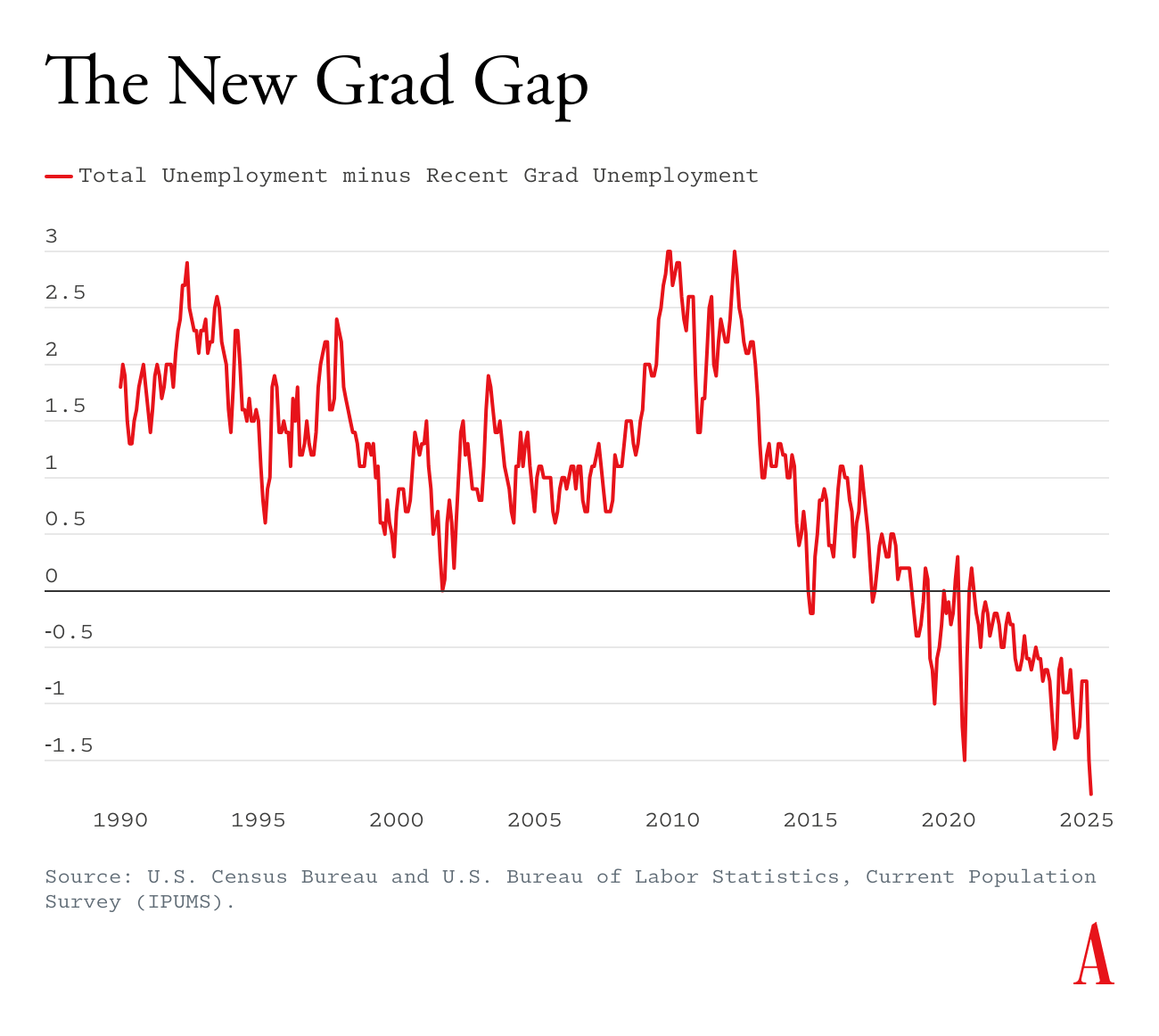

Consider, then, a novel economic indicator: the recent-grad gap. It’s the difference between the unemployment of young college graduates and the overall labor force. Going back four decades, young college graduates almost always have a lower—sometimes much lower—unemployment rate than the overall economy, because they are relatively cheap labor and have just spent four years marinating in a (theoretically) enriching environment.

But last month’s recent-grad gap hit an all-time low. That is, today’s college graduates are entering an economy that is relatively worse for young college grads than any month on record, going back at least four decades.

The strong interpretation of this graph is that it’s exactly what one would expect to see if firms replaced young workers with machines. As law firms leaned on AI for more paralegal work, and consulting firms realized that five 22-year-olds with ChatGPT could do the work of 20 recent grads, and tech firms turned over their software programming to a handful of superstars working with AI co-pilots, the entry level of America’s white-collar economy would contract. The chaotic Trump economy could make things worse. Recessions can accelerate technological change, as firms use the downturn to cut less efficient workers and squeeze productivity from whatever technology is available. And even if employers aren’t directly substituting AI for human workers, high spending on AI infrastructure may be crowding out spending on new hires.

Luckily for humans, though, skepticism of the strong interpretation is warranted. For one thing, supercharged productivity growth, which an intelligence explosion would likely produce, is hard to find in the data. For another, a New York Fed survey of firms released last year found that AI was having a negligible effect on hiring. Karin Kimbrough, the chief economist at LinkedIn, told me she’s not seeing clear evidence of job displacement due to AI just yet. Instead, she said, today’s grads are entering an uncertain economy where some businesses are so focused on tomorrow’s profit margin that they’re less willing to hire large numbers of entry-level workers, who “often take time to learn on the job.”

No matter the interpretation, the labor market for young grads is flashing a yellow light. It could be the signal of short-term economic drag, or medium-term changes to the value of the college degree, or long-term changes to the relationship between people and AI. This is a number to watch.

#Sign #Competing #College #Grads

Thanks to the Team @ The Atlantic Source link & Great Job Derek Thompson