Chef Nobu serves his famous miso cod with a side of inspiration in a new documentary

June 27, 2025

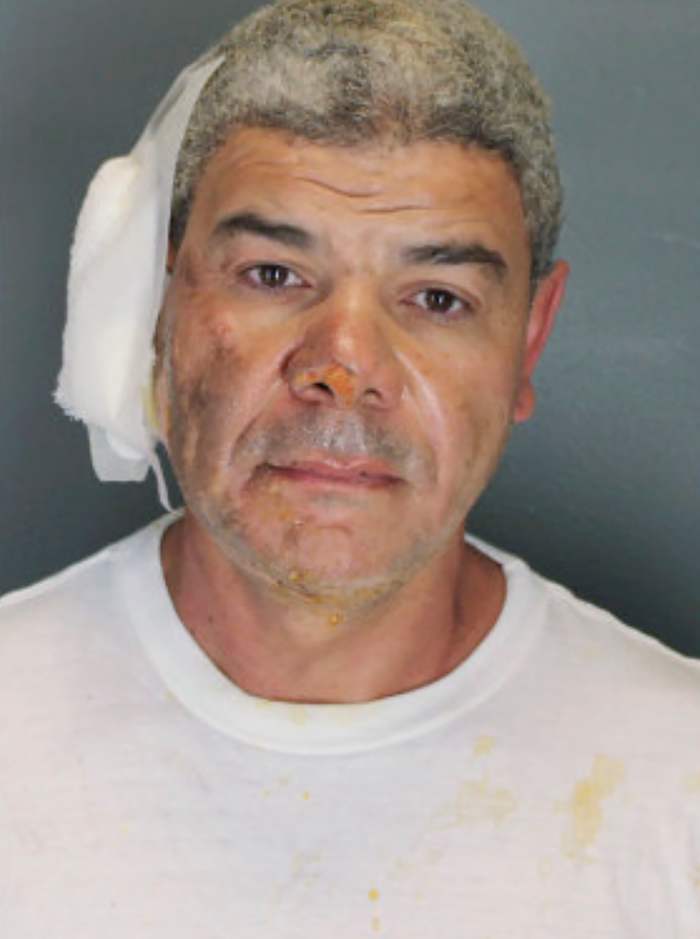

Man pleads not guilty to hate crimes in attack on Colorado demonstration for Israeli hostages

June 27, 2025Looking Back, Moving Forward—a new podcast from Ms. Studios hosted by Carmen Rios—explores what we can learn from the last 50-plus years of Ms. to inform where we go next.

You don’t have to look too far back in American history to know that these times are less unprecedented than we think.

In fact, many of the most regressive and dangerous political ideas threatening the feminist progress we’ve made in the last 50-plus years have deep roots in our nation’s history.

Women are still fighting for equitable political power, in large part because our political systems were never designed for women, people of color, or other communities at the margins to be heard.

The abortion bans taking shape across the country are part of an ongoing campaign to criminalize women’s reproductive health care that dates back nearly 200 years, when the American Medical Association formed with the intent to disempower female midwives and nurses.

One in four women today is a survivor of sexual assault, a direct result of archaic laws that essentially categorized women as the property of men—whether they were their enslavers or their spouses.

For generations, women in the U.S. were excluded from educational and economic opportunities—and, by and large, had limited access to and control over their own finances. Today, laws continue to fail to protect women from widespread economic segregation and discrimination—and women, especially women of color, are more likely to live in poverty.

“We had this myth—that’s been an incredible problem in all kinds of ways — of American exceptionalism,” Lenore Palladino, associate professor of economics and public policy at UMass Amherst and Ms. contributor, told me during an interview for the new Ms. Studios podcast, Looking Back, Moving Forward. ”We didn’t think we would go back. We didn’t think that that could happen here. The only silver lining I see, in some ways, in this moment, is that the myth is broken.”

Looking Back, Moving Forward is a five-part series exploring the intertwined histories of Ms. magazine and the modern feminist movement, and where the fight for gender equality must go next. I’m your host—and for each episode, I spoke to Ms. writers and editors and the feminist thought leaders and activists who have continued to define and redefine this movement.

Sexism, racism, classism—our feminist foremothers fought these forces for centuries. That’s why now, more than ever, we need to learn from the activism that got us this far.

”All of these forces have pressed on and limited our review of what’s possible,” Aimee Allison, founder of She the People, told me during our interview for the show. “We have to break the spell that we have been under about what this country is,” she added, “in order for us to create something new.”

That’s exactly what Looking Back, Moving Forward aims to do. In each episode, I chronicle the changes we’ve seen in one of five major parts of the feminist movement—the campaign for equitable political representation, the fight for reproductive freedom, the charge for economic justice, the struggle to end gender-based violence, and the urgency of enshrining the Equal Rights Amendment—and talk to the feminists who continue to work at the frontlines of these critical battles for gender equality.

By looking back at the stories of our collective history shared in more than 50 years of Ms. reporting, I believe we can find the map for how to move forward—toward the intersectional feminist future we’re fighting for.

The first episode of Looking Back, Moving Forward comes out next week, on the Fourth of July, and examines the growing political power feminists hold as voters and candidates through interviews with Allison, pollster Celinda Lake, New Mexico state Senator Angel Charley, constitutional law scholar Julie C. Suk, RepresentWomen founder Cynthia Richie Terrell, and Ms. contributor and gender in politics expert Jennifer M. Piscopo.

Tune in to the trailer for Looking Back, Moving Forward—and be sure to like, follow and subscribe to the show on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, iHeart Radio, or wherever you get your podcasts to to be sure you won’t miss a second of the conversations and revelations to come!

We got here because we have the gender ruling class desperately holding onto their privilege—using any means necessary.

Susan Frietsche, Women’s Law Project

“When we tell the story of American slavery… we ignore terminologies that are really important,” Michele Goodwin, Ms. Studios executive producer, host of Ms. podcasts including On The Issues, and Linda D. & Timothy J. O’Neill professor of constitutional law and global health policy at Georgetown Law, told me during our conversation about the roots of reproductive injustice in the United States. “It is a part of a story that involves dehumanization of girls and women, the failure to pay attention to the fact that they had lives, that they had purpose, that they had agency, that there were things that they were thinking about, at which time they were kidnapped and forcibly removed from their homes, from their schools, from the things that they cared about, and were put in fortresses and then had to endure a horrific voyage over to these lands, which were already being occupied, taken away, bartered—exploitation.”

That dehumanization remains an inextricable part of our most powerful governing institutions. “Misogyny is a system, patriarchy is a system, by which people who are in power extract benefits and value from people who have no rights,” Julie C. Suk, professor of law at Fordham University School of Law and author of After Misogyny: How the Law Fails Women and What to Do about It, explained to me. “In our nation, that meant enslaved African Americans and women who did not have rights, but were expected to basically take care of our posterity, just to quote the Preamble of the US Constitution, to do all the reproductive labor necessary to perpetuate the nation throughout the generations.”

”Even when we corrected that,” she added during our conversation around women’s limited political power, “by way of the 19th Amendment and by way of the amendments that were adopted after the Civil War, creating formal equality or a formal right to vote, unabridged on account of sex, [it] was not enough to dismantle the vast infrastructures, enforced by law, that continued the extraction of value and the expectation that women perform the reproductive labor and raise the nation without compensation and without other important rights. … Even if we formally have the right to vote and we formally have equality, the entire infrastructure by which women have been excluded from real participation in decision making and power, that continues.”

In other words: “We got here because we have the gender ruling class desperately holding onto their privilege, using any means necessary”—as Susan Frietsche, executive director and legal director of the Pennsylvania-based Women’s Legal Project, told me while we discussed the power of state ERAs (and why it’s long past time for one in the U.S. Constitution).

That’s why, as Gaylynn Burroughs, Ms. contributor and vice president for education and workplace justice at the National Women’s Law Center, observed while we spoke about women’s economic justice, “there’s so much systemic inequity still. We still are facing the consequences of historical and present-day discrimination.”

Throughout this sordid history, however, feminists have persisted. The ways in which they came together, harnessed their collective power, and fought for change are potent reminders of the possibilities before us.

“These things are not natural. These things are recent,” Jane Caputi, Ms. contributor and professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Florida Atlantic University, asserted during our conversation about issues of gender-based violence. She recalled that “Gerda Lerner says patriarchy has only been around for 7,000 years. It wasn’t always there.”

The good news? That means it can be changed.

We weren’t wrong. We stand for something extremely powerful. And we have a legacy of women who came before us that are going to actually show us the way forward.

Aimee Allison, She the People

Premilla Nadasen, who has done extensive research and writing on domestic worker organizing in the U.S., including in Ms., told me in our interview for the podcast that she was drawn to the subject because of their unique approach to organizing.

“Domestic workers were organizing in public places,” Nadasen, who is professor of history at Barnard University, explained to me. “They were organizing on playgrounds. They were organizing in laundry rooms. They were organizing on buses. They were organizing outside of their places of work because they couldn’t organize in their place of work. They were single employees in a household behind closed doors. They organized both documented and undocumented workers… [and] they weren’t only organizing people by employer. They directed their demands to the state.”

“The takeaway here for me about this innovative organizing is that we, as feminists today, like domestic workers in the 1970s, and in the early 2000s, need to think outside the box,” Nadasen added. “We, at this moment, could use this really difficult moment to kind of think much more expansively and really think in new and different ways about how to organize a feminist movement.”

“You cannot talk about the need for guaranteed income without talking about how Black women in the South have systematically been locked out of the economy for generations, and what that looks like,” Aisha Nyandoro, the founding CEO of Springboard to Opportunities, remarked to me during our conversation about economic justice. “When we started the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, it really, for me, was about that lived legacy. How do we continue the work that Johnnie Tillmon started with welfare reform?” she asked, referencing the welfare activist whose piece, “Welfare Is a Women’s Issue,” was published in the first issue of Ms. “How do we not only continue that work, how do we bring it forward, and not only how do we bring it forward, how do we see what is needed next? It’s all about legacy and continuation.”

Honoring that legacy means knowing our past—and continuing to articulate and advance the visions that have brought feminists together for generations.

“I think there’s a lot of people feeling all is lost right now,” Allison emphasized to me, “and I can only say that we weren’t wrong, we stand for something extremely powerful, and we have a legacy of women who came before us that are going to actually show us the way forward.”

Ms. was one of the first magazines to take on conversations about rape, abortion, domestic violence, women’s political power, and women’s relationship to economics and class. Sparking dialogue—and change—around these issues remains critical 50-plus years since its first issue, and so do the strategies for confronting them that have been, and continue to be, articulated and amplified in the pages of Ms.

“At the same time that we’re trying to mitigate harm, we’re trying to also make sure that we are working towards seeding strategies for creating this long-term vision we have of gender justice,” Burroughs told me.

That strategy—“block and build”—is the way through this current moment for our movement.

“The history of the United States has been a long struggle that will continue,” Cynthia Richie Terrell, Ms. columnist and founder of RepresentWomen said. “We’re going to have to do some incredible collective organizing to protect what we believe in about this country. … We’ve got to push our own major women’s led democracy and everything else movement, and use all the strategies that we can think of to get that job done and reach that vision of a gender-balanced world.”

We also cannot leave anyone behind in our fight for gender justice, especially at a time when the most vulnerable women are under endless attack. Over and over again, the women I spoke to for Looking Back, Moving Forward emphasized the urgency of building an inclusive and truly intersectional movement that has the power, the might, and the mission to meet this challenging moment.

“The slippery slope that got us here was… the lie of white supremacy and the American dream, and there’s a right way to have children, and if you just do it the right way, then you’ll be fine,” Renee Bracey Sherman, founder of We Testify and host of the abortion history podcast The A-Files, told me while we discussing her book, Liberating Abortion: Claiming Our History, Sharing Our Stories, and Building the Reproductive Future We Deserve. “Now we’ve got folks who have miscarriages who can’t get mifepristone or misoprostol and are being criminalized for the outcomes of their pregnancy. We have folks who need abortions later in pregnancy for health indications and they also can’t get it because the exceptions don’t work. Because they sold you a lie that if they only criminalize these people who are unworthy everyone else will be fine, but no—that was actually the way to get to you, too.”

“We need to make sure that everyone is brought into this movement and that everyone, especially folks who are the most vulnerable, especially folks who have been historically left behind, are front and center in the policies that we’re creating,” Rakeen Mabud, Ms. contributor, economic expert and independent consultant, said during our interview. “This is not a moment to be shy or exclusive. This is a moment to welcome people with open arms and make sure that, when we put forward policies, they’re policies that will really support people of all kinds—women, nonbinary folks, trans folks—to let folks live their own lives, live their fullest lives, make the choices that are right for themselves, for their families, for their jobs, their bodies.”

“If we’re willing to challenge the old assumptions and the old biases that have limited the women’s movement,” Allison added during our conversation, “there’s a lot of places that we can go.”

We will get on the other side of this. Because it is just a moment. It’s not the end of the story.

Aisha Nyandoro, Springboard to Opportunities

Our shared histories show us that change is possible, even in impossible times. They also show us that backlash, regression, division, fearmongering, scapegoating—they’re all par for the course when it comes to our work this movement.

“We can’t ignore what’s taking place at the state level that may seem to be innocuous, may seem to be sort of strange, may seem to be as if it’s so far out of reach, that it could never happen,” Goodwin told me. “There are so many lessons that we have in front of us, both historic as well as present, that tell us that we should not discount the things that seem strange, wild, and ludicrous… What we see is a path that is cruel and that leans towards unusual.”

Our job is to know that in the face of that cruelty, we can’t back down. Instead, the women I spoke to for Looking Back, Moving Forward were unanimously adamant that we have to move forward.

“There will be backlash,” Caputi warned me. “It’s a sign that we are making inroads. Take heart from what we can learn from women’s history. I do think we will prevail, because this road toward violence and hierarchy and masculinity — where is it getting us? …We can’t stop. We have to keep showing that there is another way and living that way.”

“We sink or swim together,” Debra Katz, a civil rights and employment lawyer whose clients have included Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and multiple women who came forward to accuse Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault, echoed that sentiment when she spoke to me for the show. “These issues are all connected. We have to work in coalition. We have to be relentless… We’re tired, but people are at risk, and we just have to be resolute, and choose our battles carefully—and there will be wins.”

“I was born in 1971, about the time that the Title IX legislation was passed,” Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey told me when we spoke for the podcast. “I was able to go on and play basketball in college, I was able to go on and play basketball professionally… and I probably wouldn’t have ever ended up running for Attorney General, or Governor, were it not for those things… I recognize that the opportunities that I have, they come about because people were willing to stand up and fight for those rights, fight for those laws, and it’s my obligation to, and my responsibility to, carry on for this generation and the next generation.”

Nyandoro shared with me during our conversation that she recently spoke with an elder about the threats of this moment, and that she was reminded, during that conversation, “that my responsibility is just to hold the root and to know that I am not the only one holding the root — that it’s a big, beautiful tree, and that there are so many individuals around, holding their root. If we all continue to do that, and don’t get in despair, quit the doom-scrolling and…just hold the root, we will get on the other side of this. Because it is just a moment. It’s not the end of the story.”

Let’s learn from our collective history—and write the next chapter in that story—together.

Tune into the Looking Back, Moving Forward trailer below and like, follow and subscribe to the show on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, iHeart Radio or wherever you get your podcasts so you never miss an episode!

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘200522034604820’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

Great Job Carmen Rios & the Team @ Ms. Magazine Source link for sharing this story.