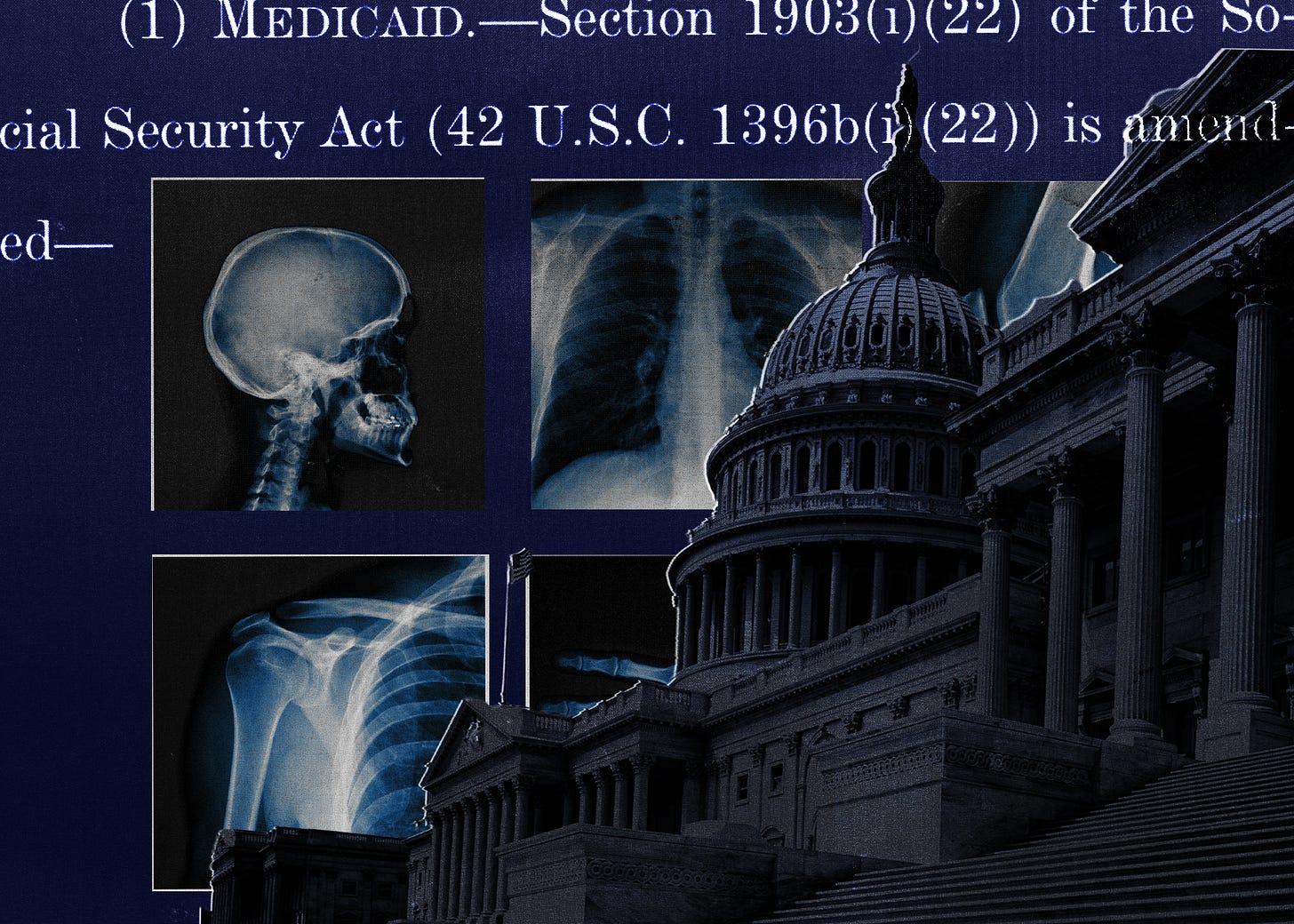

Trump Gets Qatari Jet, While Families Pay More.

May 13, 2025

Tim Miller Unloads on Biden’s Inner Circle

May 13, 2025FOR A LITTLE WHILE THERE, it was easy to think Republican leaders on Capitol Hill had discovered their kinder, gentler selves.

The House Energy and Commerce Committee on Sunday evening unveiled its long-awaited proposal to cut Medicaid spending. And the first thing many analysts noticed—as I certainly did—was that the legislation did not include some of the most radical ideas under consideration, like across-the-board reductions in the federal government’s share of Medicaid funding.

The ditching of those proposals was a concession to moderate and swing-state Republicans who said they could not support severe cuts to the program on which more than 70 million Americans now depend for medical care. “Republicans Propose Paring Medicaid but Steer Clear of Deeper Cuts,” an early headline in the New York Times announced.

But then the details of the GOP proposal became clear—and so too did the massive impact it could have on the lives of low-income Americans.

The GOP legislation still contained rather significant cuts to Medicaid, including requirements that enrollees show they are working (or qualify for a limited set of exemptions) and requirements that states check eligibility more frequently.

The Republicans pushing these plans argue that work requirements reduce dependency on public programs—and that enrollment and eligibility changes will help reduce “waste, fraud, and abuse.” They are also happy to have the $625 billion in projected savings from those proposals, because they believe in smaller government and because they are looking for ways to offset the cost of the multi-trillion-dollar tax cuts in the same bill.

But most people on Medicaid already work or have a reason like a disability that they can’t, so that the main impact of work requirements is to make enrolling and staying on Medicaid more difficult.

The same goes for requiring states to check eligibility more frequently, which actually requires governments to spend extra money on verification—and leads, again, to large numbers of people losing their Medicaid even though they still qualify for it.

As Loren Adler, associate director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on Health Policy, put it to me Tuesday, “A lot of this is really just about erecting barriers to enrollment and re-enrollment, and then, more broadly, just narrowing eligibility.”

It’s true that some people who fall off the Medicaid rolls inevitably find their ways to alternative sources of health coverage. But that coverage may not be as good and the majority end up with nothing at all—which, it turns out, is exactly what the Congressional Budget Office has projected will happen if the Republican plan is enacted. In an analysis published Tuesday, CBO predicted the GOP Medicaid cuts would increase the number of uninsured Americans by 7.6 million.

“The fact that Republicans have for now backed off politically visible changes like eliminating the federal match for Medicaid expansion leaves the impression that these cuts are moderate,” Larry Levitt, executive vice president at the health policy research organization KFF, told me over email. “But, the level of the Medicaid cuts and the very big expected effects on health coverage illustrate that these are hardly modest changes.”

Indeed. A 7.6 million increase in the number of uninsured Americans would represent a massive jump, equivalent to about 30 percent of the total uninsured population today.

And even that data point doesn’t fully capture the impact of what Republicans are proposing—in part, because it’s not just the newly uninsured who would feel it. Plenty of other people would, too, so with a key House committee about to start deliberations—and kick off weeks’ worth of debate—now would be a good time to look closely at who they are.

WHEN YOU THINK OF MEDICAID, you probably think of poor children and working-age, able-bodied adults. But about one in four Medicaid beneficiaries are either elderly or people with disabilities.

Most of them have Medicare, which covers most of their ongoing medical expenses. But Medicare has some big gaps in coverage, including big out-of-pocket expenses for doctor visits, hospitalizations and prescription drugs. Plus there are some expenses, like long-term care, it doesn’t cover at all.

Low-income seniors and people with disabilities can get Medicaid to fill in those gaps. And it would be difficult to overstate how vital that Medicaid coverage is for these people, given the frailty of the population in question and their limited, sometimes nonexistent financial resources. Among other things, Medicaid is the single largest payer of nursing-home care.

But the vulnerability of this population means many of them are particularly ill-equipped to handle the procedures of enrolling and then staying on Medicaid. For that reason, the Biden administration used its regulatory authority to streamline the process, by (for example) requiring less frequent checks of eligibility and more seamless procedures for switching between government plans.

The Republican bill rescinds that rule and several related ones, on the theory that they create opportunities for fraudulent enrollment. But the evidence of widespread fraud is iffy and there are other ways to combat it besides simply rolling back the new rule—which, CBO estimates, would cause something like 2 million seniors and people with disabilities to lose their Medicaid.

They wouldn’t show up in the tally of the uninsured, because they’d still have their Medicare. But they’d be facing much higher expenses, in some cases with no way to pay their bills.

“Because Medicaid is covering the things that Medicare doesn’t cover, when somebody who’s dually eligible loses access to Medicaid, it could mean losing access to supports that they need for their activities of daily living,” Nicole Jorwic, longtime advocate for people with disabilities who is now with the advocacy organization Caring Across Generations, told me in an interview. “It could mean they’re going back to relying on families, or could be at risk of being on the street.”

Note that seniors and people with disabilities wouldn’t be the only Medicaid beneficiaries facing additional health care expenses.

Today the law mostly prohibits states from charging Medicaid beneficiaries premiums, or having them pay more than token out-of-pocket costs, on the theory that even small co-pays can be more than low-income people can afford.

The Republican proposal would require states to start charging at least nominal copays to some Medicaid beneficiaries with incomes above the poverty line, which for a family of three is about $27,000 a year right now.

That’s no small thing. Research and past experience has shown that, when out-of-pocket costs get high, people will sometimes ration their own medication—which, if you have a condition like diabetes or heart disease, can lead to complications that can keep you out of work, require expensive hospital care, or both.

THERE’S ANOTHER BIG REASON to believe that the full impact of the Republican proposal will be anything but modest. That’s because of the changes Republicans have in mind for the Affordable Care Act.

A separate part of the Republican legislation would make a number of seemingly technical adjustments to Obamacare, like shortening the open enrollment period and tinkering with formulas for calculating how generous insurance plans must be.

The official rationale for these changes is to cut down on enrollment fraud, which really does seem to be an issue. But the extent to which fraud is a massive problem is very much open to question, as is a strategy of trying to prevent it that focuses on individual applicants rather than brokers who appear to be the primary instigators (because they get commissions on sales).

“All of these policies are premised on the idea that insurance brokers are perpetrating fraud, but the proposed interventions don’t target bad brokers, they just make it harder for enrollees to get and stay insured,” Adrianna McIntyre, a health policy professor at Harvard, told me.

The proposed GOP changes to the Affordable Care Act would, according to CBO, cause the number of uninsured Americans to rise by almost 2 million. That’s above and beyond the 7.6 million who’d become uninsured thanks to the Medicaid cuts.

It’s also in addition to a whole other, big change coming to the Affordable Care Act regardless of whether some version of the Republican cuts pass. There will soon be an expiration of a temporary boost in subsidies to buy insurance that Biden and the Democrats enacted while they were in control of the government.

Those extra subsidies are widely believed to be the primary reason enrollment in the private Obamacare plans—the ones you get through HealthCare.gov or state-run marketplaces like Covered California—have reached record levels. But they are set to lapse at the end of this year.

And while Democratic leaders in Congress have been agitating to extend them, Republicans so far have not shown much interest—in part, because it really would cost a lot of money, on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars if done for the full ten-year budget window.

The tradeoff to not spending that money, as Republican leaders appear to prefer, is fewer people insured. Those several million individuals won’t show up in the CBO projections because of CBO accounting conventions: Allowing the temporary subsidies to expire on time isn’t considered a “cut” that CBO registers as a change. But they will be real people who no longer have insurance.

“The partial analysis we already have from CBO points to coverage losses of close to 10 million,” Matthew Fiedler, a health economist at Brookings, told me early Tuesday, as projections were still coming in. “Add in the provisions CBO hasn’t gotten to yet and the looming expiration of the enhanced Marketplace subsidies, and we’re looking at coverage losses well north of that.”

“People did not ask for higher health care costs, or more complexity, or fewer benefits,” Sarah Lueck, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, told me. “That’s not what they wanted.”

But “if this moves forward, that’s what they’re going to get.”

Great Job Jonathan Cohn & the Team @ The Bulwark Source link for sharing this story.