ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

My Digital Pregnancy

May 6, 2025

Congress Is Preparing to Hit Universities Where It Hurts

May 6, 2025Two years after Arizona officials revealed a $2.5 billion Medicaid fraud scheme that targeted Native Americans seeking treatment for addictions, the state has recovered just a fraction of the taxpayer funds lost to fraud.

The Arizona attorney general’s office is leading the criminal investigation into the network of behavioral health providers and sober living homes that from 2019 to 2023 exploited the American Indian Health Program to obtain inflated Medicaid payments. Investigators found fraudulent operators didn’t provide the services they’d billed for and sometimes allowed patients to continue the substance use for which they had sought treatment.

The state has so far indicted more than 100 individuals and recouped $125 million — or about 5% of the funds the state estimates it paid to bad actors.

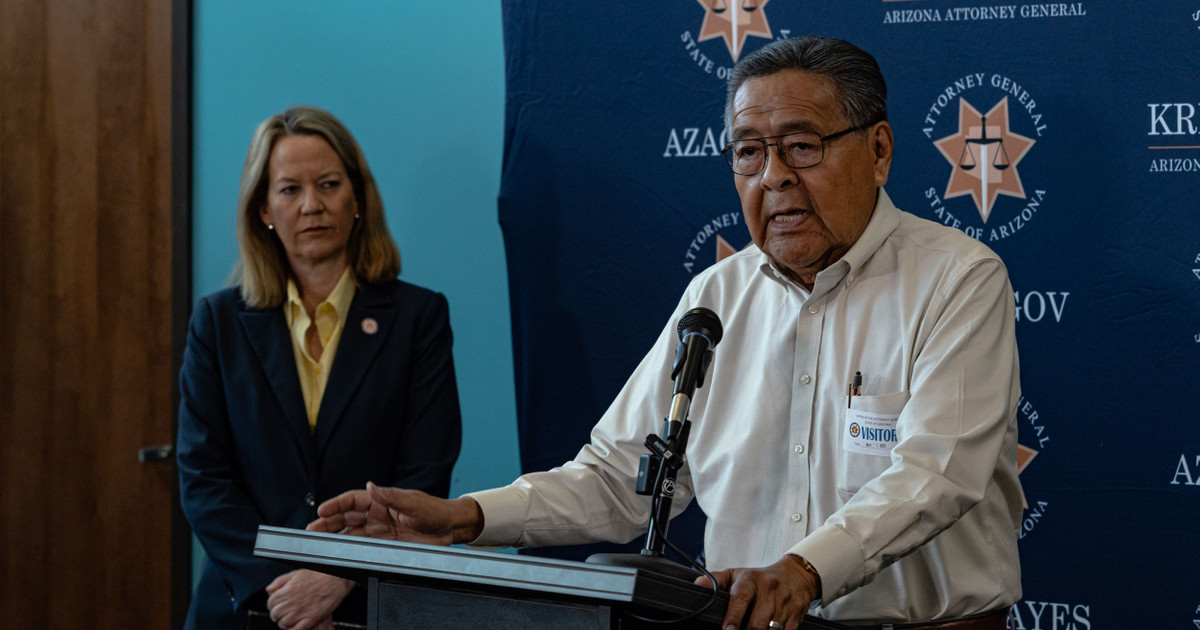

Attorney General Kris Mayes said in a May 1 press conference that she hopes to retrieve “at least hundreds of millions” from fraudsters. But she warned that “it’s hard, because what happens is these … criminals get the money, they buy lavish homes, they buy multiple expensive cars, they hide the money offshore, they spend the money in ways that is unrecoverable.”

“My team is working day in and day out to seize those assets,” Mayes said.

The Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System struggled to rein in the rampant fraud under two governors, leaving more than 11,000 people vulnerable to the chaos that followed. Prior reporting by the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting and ProPublica found that at least 40 Indigenous residents of sober living homes and treatment facilities in the Phoenix area died as the state fumbled its response.

The damage also rippled out through the state’s behavioral health industry, which was nearly brought to a standstill when the agency suspended some 300 providers and enacted policies that halted or substantially delayed payments to those still operating. Those reforms included enhanced scrutiny when screening and reimbursing providers.

Gov. Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, recently signed legislation further increasing oversight of sober living homes by requiring the facilities to promptly report resident deaths. But advocates like Reva Stewart, a Diné activist who has helped Indigenous victims of the scheme through her group Stolen People Stolen Benefits, don’t think the state has done enough.

“I feel like I’m on a hamster wheel, and we’re still at the beginning,” Stewart said. “They have a lot of indictments and people being charged, but at the same time … they’re just getting a slap on the wrist.”

The U.S. Department of Justice has also indicted several individuals and is conducting parallel investigations into the fraudulent billing schemes under federal statutes.

Yet despite these state and federal efforts, it’s likely that most of the stolen taxpayer money won’t be recovered.

From 2019 to 2023, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System allowed about 13,000 unlicensed providers to enter its system, including some that exploited weak oversight by overbilling or charging for services that were never delivered.

The agency also didn’t act decisively when solutions to stem the fraud were proposed internally. It initially yielded to pressure from special interest groups connected to the behavioral health industry, which argued that reforms to the fee-for-service American Indian Health plan would threaten their financial interests.

Now, AHCCCS says its efforts to unravel the crisis could take many years, describing its investigation as a “highly complex and manual process.”

Officials must review improper payments, whether they were obtained by fraud or not, on a case-by-case basis. Though providers are required to repay AHCCCS as soon as they become aware of overpayments, they often cannot do so in one lump sum. Repayments may occur over months or years.

Because state Medicaid agencies receive much of their funding from the federal government, improper payments come with added financial consequences: States must repay the federal government for its share.

In Arizona, the federal government covered 70% to 76% of Medicaid costs between 2019 and 2023. The rate was even higher for people who received services through the American Indian Health Program.

AHCCCS has repaid $49.1 million to the federal government since January 2023, according to spokesperson Havona Horsefield, who has since left the agency. That amount will likely grow as AHCCCS continues to review fraudulent cases.

The agency is not, however, required to reimburse the federal government for overpayments made to facilities that are now bankrupt or out of business. Of the 322 providers suspended on suspicion of fraud, 90 have closed, according to AHCCCS.

The agency could not provide an estimate of how much those providers were overpaid, but said it notifies the attorney general when a provider goes out of business and provides information to support criminal cases against them.

State Sen. Theresa Hatathlie, a Democrat from Coal Mine Mesa on the Navajo Nation, has been critical of the state’s response and continues to call for stricter regulation of sober living facilities. During a March floor vote, she expressed frustration over the reforms Hobbs later signed into law, contending they did not go far enough.

“It’s time to stop protecting bad actors or even those people who continue to allow bad actors to keep coming back,” she said.

As the state slowly works to untangle the fraud and recover taxpayer funds, national debates over Medicaid’s future are intensifying. Republican majorities in both Arizona’s Legislature and Congress are pushing to cut Medicaid to offset President Donald Trump’s proposed tax cuts. Among their justifications are fraud and abuse of the system.

Health policy experts, however, say that most Medicaid spending pays for legitimate care, and that fraud is typically committed by a small number of providers — not patients.

Instead of the current system where the federal government covers a larger share of Medicaid costs in lower-income states, conservatives are advocating to cap Medicaid funding tied to inflation, a model that would shift more of the cost to state budgets.

Arizona is one of nine states where such a change could trigger the end of Medicaid expansion, which currently insures 648,000 low-income residents, or about 30% of AHCCCS recipients.

Despite Medicaid’s uncertain future, Arizona officials are pressing forward with efforts to address the lasting damage the fraud scandal inflicted on tribal communities. In November, Mayes announced a $6 million grant initiative offering up to $500,000 per organization to fund victim compensation and housing support for those displaced or otherwise affected by fraudulent treatment centers. Recipients include tribal nations and Native health organizations.

But Stewart says the state’s work is far from over, and many of those harmed have yet to see real accountability or support.

“They call it a travesty … and they want to get justice,” she said. “But where’s the justice when it comes to the amount of deaths that we have, the amount of Native relatives that are still missing?”

Christopher Lomahquahu, a Roy W. Howard fellow at the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, contributed reporting.

Great Job by Jasmine Demers, Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting & the Team @ ProPublica Source link for sharing this story.