Transcript: Trump Blurts Out Revealing Admission on Abrego Garcia Case

April 28, 2025

The Far-Right Origins of Donald Trump’s Self-Deportations

April 28, 2025Elisha Fye Jr. grew up hearing his father’s stories of the Jim Crow South. There, Elisa Sr. was born on a plantation in 1918 and one of 14 children in a family of sharecroppers who toiled all year for just $200 and a share of the crops in Vidalia, Georgia. After a violent run-in with a white man forced him to flee to the Army, the elder Fye fought in World War II and then moved to New York City, where he rebuilt his life — and the city — from the ground up.

In New York, Elisha Sr. helped build the underwater Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel before working in the boiler room of Cooper Park Houses, a public housing complex. There, he would raise Fye and his five other children alone after his wife died.

Decades later, Fye is now leading the fight to protect that same affordable housing community — owned by the New York Housing Authority — against funding cuts and privatization schemes. He is frustrated that the federal government fails to see the hard work and sacrifice that define the lives of those living in subsidized housing. Over the past decade, his community has fought and won battles against a fossil fuel company and a private buyer who attempted to purchase the complex.

This legacy of perseverance is now under threat as federal funding for subsidized housing faces deep cuts and privatization efforts. The Trump administration is proposing a dramatic — and, for many, devastating — transformation of the country’s support for low-income renters. The administration has proposed cutting billions of dollars in funding for government-subsidized housing, including a $1 billion program to preserve and renovate aging affordable housing units and a program used to house people escaping domestic violence.

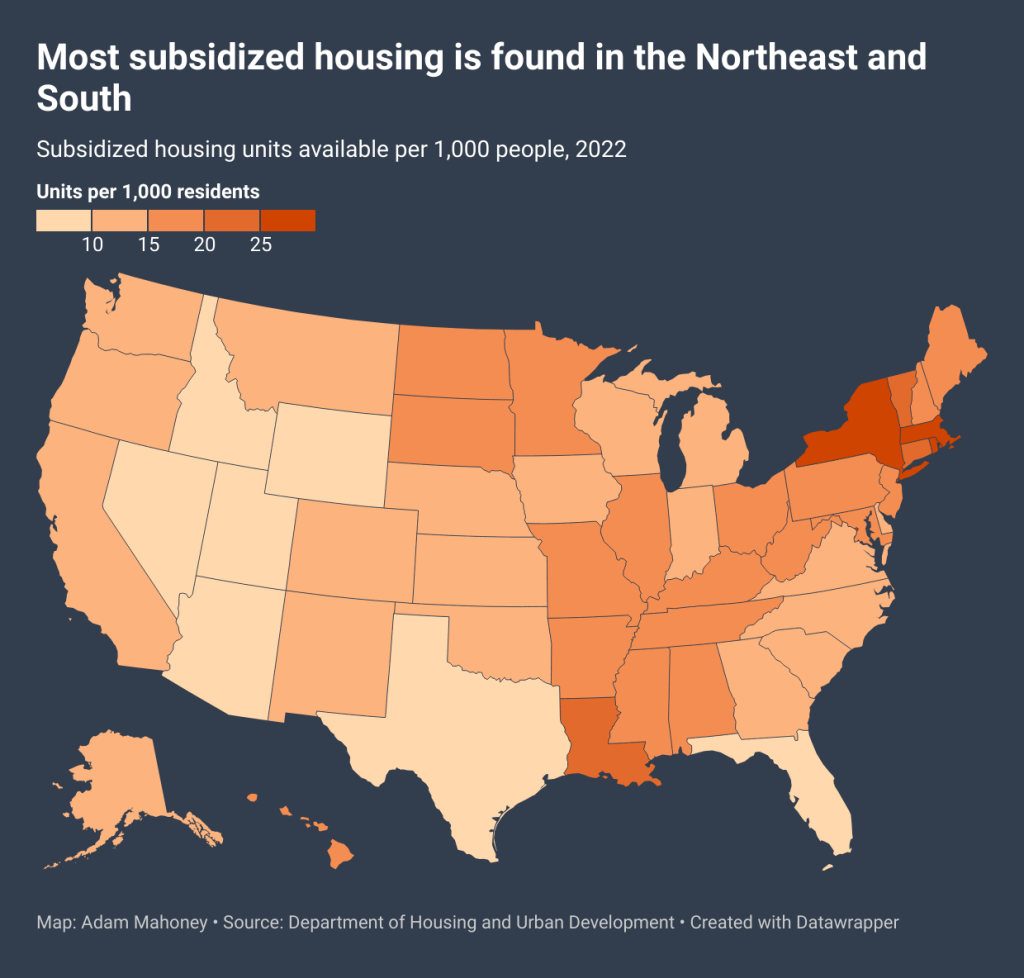

Black people make up about 45% of public housing residents and 33% of government-subsidized private housing, despite making up about 12% of the population. In some cities across the Northeast like Boston and Washington, D.C., and across the Gulf Coast, as many as 40% of all rental units are subsidized. At the state level, Rhode Island, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Louisiana have the highest number of subsidized housing units per capita. By far, New York City has the most subsidized units, with roughly 25% of NYC’s Black residents living in subsidized housing.

“I fear the federal government and Trump has no respect for the Black family at all. I worked for 40-something years, my father worked almost his whole life, but our home has always been under threat,” Fye said. “I don’t think [the fight] will end in my lifetime, but we’ll keep on fighting.”

Already, there is a national shortage of 7.1 million homes for the country’s low-income renters, and a majority of Americans struggling with access to housing are in the workforce or retired.

The proposed cuts are a part of a long history of neglecting public housing and could lead to an increase in homelessness by tens of thousands of people, explained Kim Johnson, manager of public policy at the National Low Income Housing Coalition. The long trajectory of underfunding subsidized housing began when public housing, initially designed for white working-class families, saw a sharp increase in Black families moving in after World War II.

“Public housing has been systemically disinvested in for generations, and, unsurprisingly, it has its roots in racism,” she said. “With new cuts, thousands of people are going to lose the assistance that they rely on to keep a roof over their heads.”

The cuts to rental assistance align with the Trump administration’s goal of shrinking the footprint and costs of the federal government. The reductions have largely focused on reducing federal programs meant to alleviate poverty and inequality, which the administration has cast as too generous or wasteful.

With fewer vouchers and rental assistance available, Black families may be forced onto long waitlists, to double up with relatives, or risk homelessness when they can no longer afford rising rents. In recent years, homelessness has risen to record highs and people experiencing homelessness have faced threats of incarceration and fines and fees for sleeping on the street.

“The mood around here is sad right now,” said Fye, who is 72 years old and recently suffered a stroke.

He knows the current fight is as important as it might ever be.

It is estimated that roughly 1 out of 5 government-owned housing complexes are in disrepair, and more than 5% of privately owned but government-subsidized properties face the same struggles. The loss of funding for local programs and building repairs means families may see their apartments deteriorate: leaks go unfixed, heating systems break down, and mold or pests become persistent hazards.

Now the focus is on simply holding on to what little security they have left instead of improving it, Fye said.

Since January, at least $60 million in funding for affordable housing developments has been frozen or thrown into limbo, with contracts to distribute these funds canceled for two of the three national nonprofits tasked with the job. This has left hundreds of projects — and the jobs and homes they would create — at risk. At the same time, the $1 billion program to preserve and renovate aging affordable housing units is also being terminated, threatening the long-term viability of tens of thousands of apartments for low-income Americans.

What this means for Section 8

Central to these changes is the proposed overhaul of the Section 8 voucher program, which could see millions of Americans lose access to the rental assistance that helps keep roofs over their heads.

Section 8 housing, officially known as the Housing Choice Voucher Program, is a federal assistance program that helps low-income individuals and families afford housing in the private market by subsidizing a portion of their rent. Under Section 8, eligible participants typically pay about 30% of their monthly income toward rent and utilities, while the voucher covers the remaining amount, paid directly to the landlord. Due to funding limitations and landlords routinely turning down vouchers, currently, about 2.3 million households receive Section 8 assistance, but only about 1 in 4 eligible families can access the program due to these constraints.

The administration is considering replacing vouchers with more limited state-run grants. Unlike the current program, which adjusts funding based on actual housing costs and needs, state block grants would likely be capped and less responsive to rising rents. Proposed changes may include time limits on assistance and restrictions on eligibility for certain groups, such as mixed-status immigrant families. Advocates said this move would likely result in fewer federal dollars reaching families in need and put even more pressure on already overstretched local and state agencies.

Additionally, the government is expected to allow the Emergency Housing Voucher program, which gave rental assistance to 60,000 families and individuals fleeing homelessness or domestic violence, to run out of money. It would be among the largest one-time losses of rental assistance in U.S. history, leading to a potential historic increase in homelessness, according to the Associated Press.

Russell Vought, the director of the federal Office of Management and Budget, who will play a role in what funding cuts are pushed forward, previously endorsed an end to the federal voucher program. He said the Section 8 program “brings with it crime, decreased property values, and results in dependency and subsidized irresponsibility.”

Residents like Fye are already grappling with shuttered community initiatives, stalled repairs, and the looming risk of displacement. Community programs that once offered after-school care, health services, or tenant advocacy are being shut down, leaving residents isolated and without support.

“The evil, nasty part about this, especially with the idea of these programs being ‘fraudulent and wasteful’ is they’re only talking about programs that help many of the most hard-working yet vulnerable and needy people,” said Andreanecia Morris, executive director of HousingNOLA, a public-private partnership focused on increasing access to affordable housing in New Orleans.

Black renters are more likely to live in subsidized units with unsafe or unhealthy conditions such as faulty plumbing, unreliable heat, or broken elevators than their white counterparts, yet often pay more for these substandard homes, studies show. Without support, residents worry about their homes’ long-term safety and livability.

The proposed cuts extend beyond direct housing assistance. Enforcement of the Fair Housing Act and other civil rights protections is also being gutted. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s office responsible for investigating discrimination expected to lose more than 75% of its staff, jeopardizing the process of investigating most housing discrimination complaints and leaving many tenants with nowhere to turn for help. HUD’s workforce is being slashed by half, and a key office that helps communities recover from natural disasters is slated to be dismantled.

This chronic underfunding of subsidized housing created a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Because they put absolutely no money into its upkeep, it’s easy to point at public housing and say, ‘See, look, this is a broken program’ when, in fact, we’ve never adequately funded the program at the level needed,” Johnson said.

For Fye, while the fight continues, it is a disheartening reality: “My father picked cotton as a child and fought for this country, and even today, we’re not seen as worthy.”

Great Job Adam Mahoney & the Team @ Capital B News Source link for sharing this story.