Inspector General Probes Whether Trump, DOGE Sought Private Taxpayer Information or Sensitive IRS Material

April 25, 2025

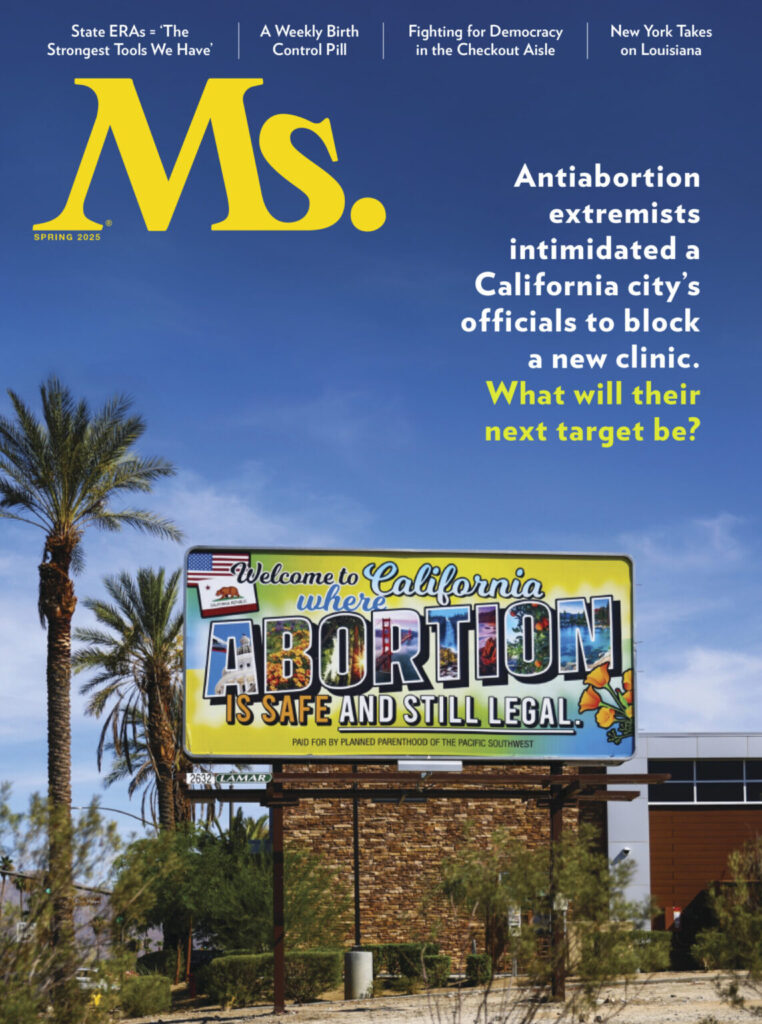

‘Barrage of Harassment, Intimidation and Violent Attacks’ on Abortion Clinics, Says National Abortion Federation

April 25, 2025This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

The world we live in has been molded by the porn we watch—and you don’t have to look too hard to find it. Instagram models hawk their OnlyFans subscriptions, sex workers post “Day in My Life” vlogs, and the market for erotic romance novels is a gold mine. People’s interest in sex is a demand that has long been met with ready supply, but porn is not an inert product: As Americans feed the multibillion-dollar industry’s growth, it gives something back to American culture.

Growing up as a teenager against the backdrop of the late 1990s, “what was obvious to my friends and to me was that power, for women, was sexual in nature,” my colleague Sophie Gilbert wrote in a recent article. “There was no other kind, or none worth having.” I interviewed her about her upcoming book on pop culture and girlhood to understand how porn became the defining cultural product of our time.

Stephanie Bai: You write that “we are all living in the world porn made.” Can you describe what that world looks like for women?

Sophie Gilbert: One of the specific things I’m noticing now is the mainstreaming of really ugly, regressive treatment in politics and mainstream culture—not just of women but of immigrants, gay people, trans people. There’s a resurgence of the kind of offensive and dehumanizing behavior that we saw in popular culture during the 2000s, and this time it’s not being doled out by gossip bloggers and celebrity commentators, but by politicians and people with massive media platforms. And my theory for why it’s happening is that certain kinds of porn have inured so many people to cruelty.

So that’s one part of it. But when I wrote that sentence, what I was thinking about was how so much of porn has really enforced the idea that men should be catered to, in all aspects of culture. That concept is deep in the recesses of our imaginations, in ways we maybe don’t realize or can’t quite put into words.

Stephanie: You detail the Y2K era of “porno chic,” when the overt sexualization of women became more mainstream in pop culture. Nowadays online, I’ve noticed more sex workers posting about their job and collaborating with popular influencers, including Logan Paul and David Dobrik. What do you think about the era of social-media sex-worker stars?

Sophie: In lots of ways, this isn’t new—it mirrors what was happening in the 2000s, when there was a real receptiveness among sex workers and people in porn to talking openly about their experiences. We had a spate of memoirs then that exposed and deglamorized the industry; Sasha Grey went from porn films to starring in a Steven Soderbergh movie and landing a guest arc on Entourage. Even the kinds of things we’re seeing now with the porn actors Bonnie Blue and Lily Phillips engaging in really extreme sexual stunts for kudos and fame—that was happening during the ’90s with Annabel Chong and Jasmin St. Claire.

Stephanie: Not only does sex sell, but sexual openness is considered “empowering” now, as you wrote. I find that criticizing porn can be seen as a regressive take—anti–women’s liberation and prudish. To what extent has the “empowerment” narrative been used to hide or excuse some of porn’s more unsavory elements?

Sophie: This was basically the point of the piece, and of my book—to try to understand why women of my generation were so easily persuaded that we couldn’t, or shouldn’t, push back against how we were being treated, both in media and in real life.

I would never try to dictate what anyone chooses to do with their body or how they present themselves. My project was more about trying to open up pathways of analysis that might explain what happened in culture during this time. But the thread through my research was that any time the word empowering came up, it was inevitably being used to sell a product that was absolutely not about making women powerful. Wonderbras are still sold as being “empowering.” There was this very dark advertising campaign in 2007 for a torture-porn movie starring Elisha Cuthbert, who was depicted on posters being tortured and killed, and the film’s executive producer defended the movie as being a story of female “empowerment.” This is one of those terms that now make me instantly skeptical when I encounter it in the wild.

Stephanie: Your essay mainly focuses on the consumption of porn in video and image form, but written or audio versions of smut (many of which are made by women) have become more popular with women in particular. When it comes to the ethics and effects of porn, is it important how porn is made, and who creates it?

Sophie: Of course! I’ve written for this very magazine in the past defending romance novels as subversive portrayals of female desire, female agency, female humanity. There is nothing wrong with smut. The reason I think and write so much about porn as a form of culture is not because it’s explicitly sexual. It’s because much of it depicts and encourages very rote, regressive, cruel, and even violent treatment of women, and there’s no way that these elements haven’t changed us.

About a year or so ago, I encountered this fascinating analysis by the social scientist Alice Evans, who argues that the status of women in a particular society can be predicted by examining how that society prizes romantic love. So it’s not surprising to me at all that so many women enjoy explicit romantic content—it’s gratifying their desires while also affirming that they are fully human and deserve to be treated as such.

Stephanie: Some readers may come away from your story thinking that you’re staunchly anti-porn or anti–sex work. Is that how you would describe yourself?

Sophie: It’s funny, because already I’ve been criticized both for being anti-porn and for not being anti-porn enough. I did figure this would happen; when writing this book, what I wanted was to be as thorough as I could in documenting and analyzing the era of porn proliferation, and then let people draw their own conclusions.

Human beings have always wanted to and will always want to think about, watch, and imagine sex. There are also certainly people such as Erika Lust and Cindy Gallop, who are out there trying to broaden the ways sexual content can cater to women, and who are trying to treat porn performers ethically. My issue isn’t with porn as a concept so much as with how certain kinds of porn have come to be so impossibly dominant culturally, in ways that leave very little room for anything else.

Stephanie: So what’s the antidote to a porn-addled culture?

Sophie: Logging off? To come back to the point about romance, I do think stories that assert people’s humanity, their complexity and lovely strangeness, go a long way.

Related:

Here are four new stories from The Atlantic:

Today’s News

- A Milwaukee judge was arrested by federal officials and charged with two felonies for allegedly helping an undocumented immigrant avoid arrest.

- Former Representative George Santos was sentenced to more than seven years in prison after being convicted of wire fraud and aggravated identity theft.

- The Trump administration is reversing course by restoring the legal status of many international students whose visas were canceled in recent weeks.

Dispatches

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

‘All We Wanted to Do Was Play Video Games’

By Spencer Kornhaber

Mald is a blend of mad and bald. It’s video-gamer slang for getting so angry after suffering a loss that you pull your hair out. I learned the word by watching Twitch, the streaming platform that is famous for turning video games into a spectator sport—and that has, of late, become an important forum for political commentary.

Read the full article.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Debate. Sinners (out now in theaters) has made a splash at the box office, but analysts want to focus on the money it isn’t making, David Sims writes.

Check the price tag. For a lot of people, it’s getting too expensive to knit or fish, Tyler Austin Harper writes. What do we lose when we’re priced out of our hobbies?

Play our daily crossword.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

#Porn #American #Culture

Thanks to the Team @ The Atlantic Source link & Great Job Stephanie Bai