Panicking Trump Walks Back His Attacks on the Fed and China

April 23, 2025

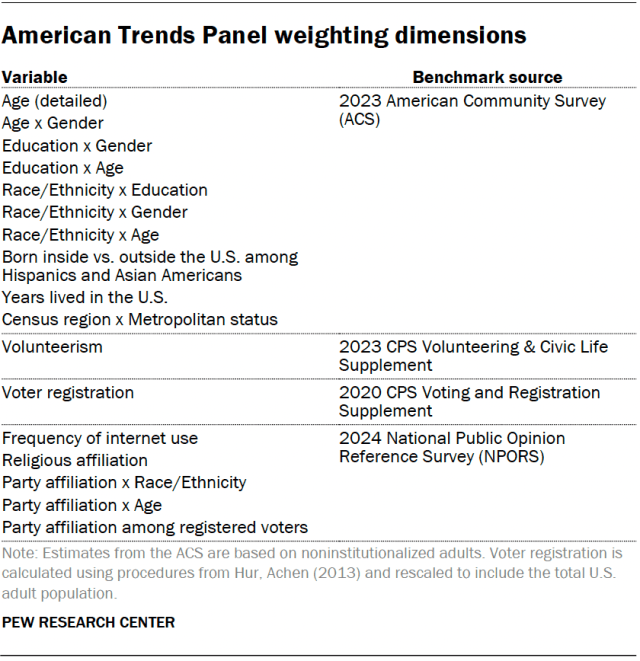

Methodology

April 23, 2025This story was first published by AfroLA, nonprofit solutions journalism for Los Angeles told through the lens of the Black community. To also reproduce or republish this article, please contact AfroLA.

In the first three days of the L.A. wildfires, lead levels detected in the air increased 110 times, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The toxic chemical burned off of old homes, businesses, and cars, filling the air with small particles that eventually rained down over large swaths of the county.

The full-scale human toll is not yet known, but experts worry about a subset of the population that may be more affected than others. The bodies of people with iron deficiency, they say, potentially absorb lead at higher rates than those who aren’t iron deficient.

Because of this, Black women are at increased risk. Last year, the CDC released data on the prevalence of anemia in the U.S. According to the report, Black women had the highest percentage of anemia than any other racial or ethnic group. Iron deficiency is the main cause of anemia globally.

Fibroids, heavy menstrual bleeding, sickle cell anemia—Black women more commonly have disorders that cause them to lose blood compared to their white counterparts and other people of color. That loss in blood contributes to higher instances of iron deficiency in women of reproductive age. Black women have the highest rates of anemia in the U.S., the leading cause of which is iron deficiency. Heavy menstrual bleeding, a condition where excessive bleeding occurs during a menstrual period, disproportionately affects Black women.

“If you are iron deficient, you’ll have four times more uptake [of lead] than someone who has the proper amount of iron in their body,” said Aaron Specht, a professor at Purdue University. He studies how people get exposed to heavy metals like lead.

That’s because, he said, as the body searches for iron to use, it may sub in heavy metals it finds in the blood and in bone, where lead is stored.

Iron is essential for a range of bodily processes, from brain function to respiration and muscle strength. It helps the body create hemoglobin, which delivers oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. When someone is iron deficient, the body tries to preserve as much hemoglobin as it can, but at the expense of physical and cognitive abilities.

“Compared to any other micronutrient deficiency, iron is the one that’s most discriminating between men and women,” said Malcolm Munro, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. Munro studies heavy menstrual bleeding and its effect on iron deficiency.

The bevy of negative health effects associated with lead exposure are well documented. No amount of lead in humans is considered safe, and even the smallest amounts can cause irreversible side effects.

Black women sit at the intersection of policies and social determinants that drive their risk of lead exposure. Living in older housing, the lasting impacts of redlining, and hair products containing lead, impact Black women’s health.

The reproductive health problems that result can be life changing.

“We live in a country that does not talk about reproductive health rights and justice issues,” said Janette Robinson-Flint, co-founder and CEO of Black Women for Wellness, an L.A.-based nonprofit that advocates for reproductive health in California.

“That’s the story of this country.”

(Elizabeth Moss/AfroLA)

Black women more at risk

The destructive Palisades and Eaton Fires started on Jan. 7. Data from air quality monitors showed that the levels of toxic chemicals leached into the air increased from Jan. 7-11, with peak levels of lead measured on Jan. 8 and 9, according to South Coast AQMD, an agency that regulates air quality. Houses were actively burning off old paint, bathtubs and other materials containing toxic chemicals.

Niki Johnson watched from her Pomona home as smoke and ash from the Eaton Fire settled over her neighborhood.

“It was panic. It was fear of having to evacuate. That was the initial fear. Then it became a health concern,” she said.

Johnson is iron deficient and anemic. She’s used to being colder than everyone else. There are periods when she gets the urge to crunch on ice, a common symptom of iron deficiency called pica. When she was younger, Johnson could eat her way back to normal iron levels–iron- fortified foods and leafy greens were and are a staple of her diet. But these days, that’s not enough.

“I have to take iron supplements,” she said. “If I don’t have to take it, I won’t, but I have to now.”

As a Black woman, Johnson is already at heightened risk for lead exposure. Johnson also walks around with a constant source of lead leaching into her body. When she was 13, a shooting left her with a bullet lodged in her lungs. She almost didn’t survive.

“They called it a miracle case.”

She spent two and a half weeks in the hospital. Breathing felt like gurgling water, she said. When she returned home, her mother closely monitored her breathing. At school, she started dancing and running track again, but she never felt she bounced back to 100%.

“[I] didn’t get any more first places.”

Today, that bullet fragment sits like a toxic reservoir in Johnson’s lungs, releasing small amounts of lead into her body when activated by heat from X-rays and MRIs.

“That’s a very troubling case,” Specht said. “While there aren’t many studies on the uptake of lead from bullet fragments, in theory, the combination of Johnson’s iron deficiency and the re-exposure from the fragments could drive her body’s absorption of lead.

“It makes sense, with the scientific knowledge that we have, that anemia would impact the uptake [of lead] from the gut, so it likely would increase the uptake from elsewhere,” he said.

The gut is one predominant way lead enters the body. The other is through the lungs. Smaller particle sizes, PM2.5 for instance, can make their way deep into the lungs, where they are deposited into the blood.

It’s easier for lead to enter the bloodstream when it’s aerosolized, or suspended in air, according to Specht. Even after L.A.’s air is cleared and toxins no longer measured on air quality monitors, lead exposure can persist for up to a decade. “Lead will unfortunately stay in the body for years to decades in their bones,” Specht said. When iron stores are low, the body will remobilize the lead stored away, working as an ongoing source of lead exposure, even when the initial threat is long gone.

Levels of toxic chemicals released during fires

In the weeks since the fires, some Altadena residents have tested their homes for toxic chemicals. One test of a single family home found lead levels up to eight times more than the EPA standard.

Historically redlined communities like Altadena tend to be located near pollutants. Restrictive covenants and racist home loan policies pushed Blacks into the most undesirable parts of cities, often the most hazardous to their health. “The redlined neighborhoods are going to have [a] higher propensity for industry, are going to have [a] higher amount of roadway traffic,” Specht said.

Redlined neighborhoods also have older housing stock. These communities tend to have houses built before 1978, the year lead was banned from paint. In Altadena, for instance, roughly 87% of homes were built before 1970. In 2011, the Environmental Protection Agency’s American Healthy Homes Survey showed that Black households had more lead based paint than white households. (In its updated survey from 2021, those homes had less lead-based paint than white homes, in part because the total percentage of homes white people lived in did not change.)

“[If] that’s the only place you can live, or that’s the place you have been driven to live, then whatever health situation you have will be exacerbated by that,” said Robinson-Flint.

But for some communities, the risk of constant exposure comes from the built environment.

“Under-resourced communities of color tend to face a higher burden or higher risk of having elevated blood lead levels,” said Jill E. Johnston, an environmental health professor at the Keck School of Medicine at University of Southern California.

Johnston studies the impact of natural and manmade disasters on marginalized communities, including disasters where lead exposure is a factor. Lead is considered a persistent chemical, meaning it takes a long time to break down. Because lead particles are heavy, they don’t travel very far, tending to settle over nearby communities.

“We think about some of these urban soils as major reservoirs of lead,” Johnston said. “Wind, construction, or other activities can really mobilize that dust back into the environment where people can breathe it in. [Particles] can go indoors, and that can continue the cycle of being exposed to it.” For lead particles that have landed in people’s backyards, it will have to intentionally be cleaned up… In neighborhoods actively recovering from the recent wildfires, lead found in ash and dust left behind could be moved around.

Ingesting a lead particle the size of a snowflake for a child to experience measurable, and often irreversible, negative health consequences–things like reduced cognitive functioning and muscle strength. While the CDC and other health organizations point out that there is no safe amount of lead to ingest, adults are slightly more resilient against the heavy metal, studies have shown.

Johnston served on a special committee that reviewed the fallout from the Exide factory, a car battery processing plant that emitted 7 million pounds of lead into the air and surrounding environment for nearly a century. In 2015, the government declared the site, located in the city of Vernon about 5 miles south of Downtown L.A., an environmental disaster and reached an agreement with the owner of the plant. Exide Technologies agreed to pay $50 million to clean up the site and surrounding neighborhoods.

To understand lead exposure among children and pregnant women during Exide’s heyday, Johnston and a team of researchers collected and studied baby teeth from families who lived in neighborhoods around Exide. By looking at different layers of teeth formed during different trimesters, Johnston was able to determine how lead contamination affected mothers and their children. They found trace amounts embedded in pre- and postnatal teeth, which varied given the mothers education level and the gender of the child (females tested higher than males).

In 2020, a bankruptcy court judge allowed Exide Technologies to abandon their Vernon factory, leaving the cost of the cleanup to California taxpayers. Given the history of communities of color living near industrial pollutants, Robinson-Flint isn’t surprised that a natural disaster like the L.A. wildfires exposed Black women once again to toxic contaminants.

“If we talk about the lead in the paint in old buildings, and we talk about the lead in the personal care products that we use, if we think about the lead in the water in Flint, Michigan, why would I be surprised?”

Great Job Ajohnston & the Team @ The 19th Source link for sharing this story.