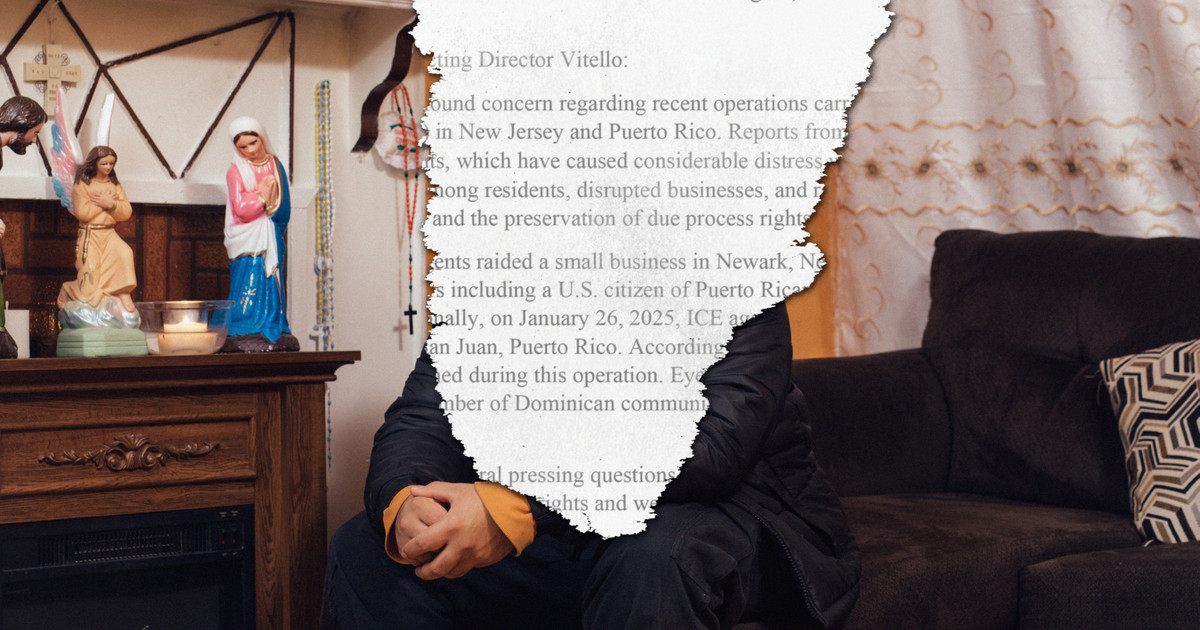

Congress Has Demanded Answers to ICE Detaining Americans. The Administration Has Responded With Silence.

April 14, 2025

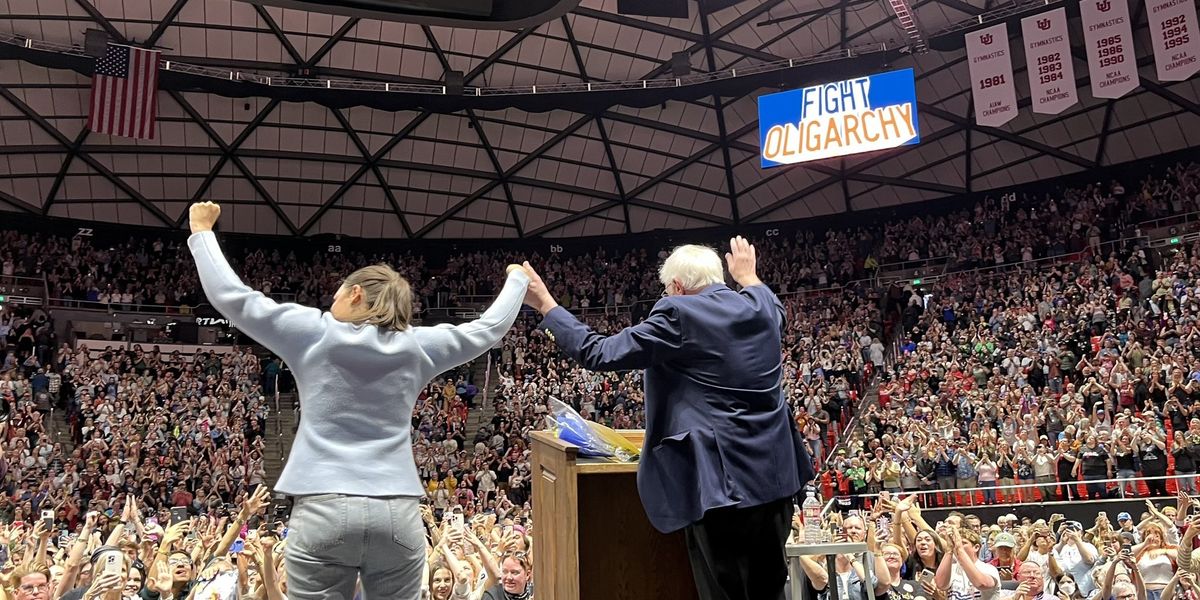

Sanders and AOC Draw Crowd of 20,000+ in Utah—A State Trump Won by Over 20 Points | Common Dreams

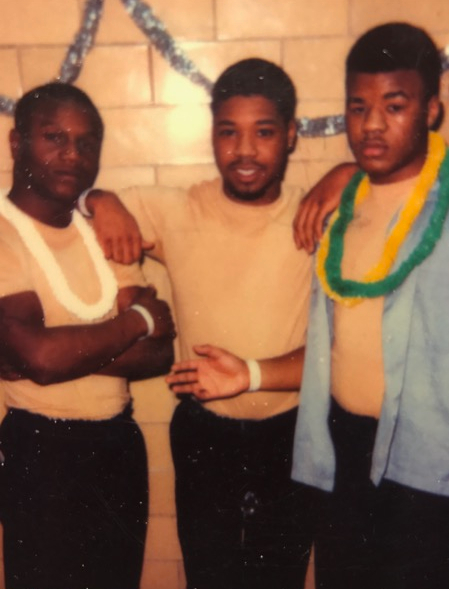

April 14, 2025As a teenager, John Pace dreamed of playing football or becoming a police officer. But growing up in Philadelphia, he found himself drawn to older people in the neighborhood — especially those with negative habits who always seemed to have the freshest clothes and the most respect. In 1985, Pace learned exactly how some of them earned their reputations. A lifestyle built on crime ultimately led him to a sentence of life in prison.

At 16, he was charged in Pennsylvania’s juvenile court system with aggravated assault, robbery, and possession of a weapon.

“When I did something wrong, I was thankful that I didn’t get caught,” Pace said. “And so, when I did get caught for this situation, I thought it was the opportunity for me to now get focused, and start getting myself together.”

Ten days later, the victim of the robbery died, altering the course of Pace’s life.

His case was amended to include a second-degree murder charge and transferred to adult court. At 17, Pace pleaded guilty to felony homicide and was sentenced in February 1985 to life without the possibility of parole.

Thirty-one years later, after a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that ended mandatory life sentences without the possibility of parole for children, Pace was given a second chance and released in 2017. Since then, the 56-year-old has joined other formerly incarcerated people who were sentenced as teens in pushing for reform of juvenile sentencing laws across the country. As part of a growing movement, they are investing in their communities, helping others combat recidivism, and using storytelling to raise awareness about youth justice laws that still impose life sentences on children. Those sentences often deny young people the chance to prove they have changed, advocates said.

The history of their advocacy stems back to the 1994 federal crime bill that created tough-on-crime laws that systemically led to the mass incarceration of Black and brown people, and especially fueled the harmful “superpredator” myth about inner-city nonwhite youth. One year later, Pennsylvania became one of 13 states and Washington, D.C., to implement “direct file” laws, which requires teens between the ages of 15 to 17 who are charged with certain felonies to be prosecuted as adults.

The measures have allowed people as young as 10 in Pennsylvania to be prosecuted as adults for serious crimes like homicide, which could result in sentences of life without parole. Because of direct file laws, Pennsylvania has the most youths sentenced to life without parole in the country, according to the Juvenile Law Center.

“We have laws in place to protect children up until a certain age, and that’s done because the law understands how vulnerable children are,” said Eddie Ellis Jr., co-director of Outreach & Member Services at Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. “They can’t vote, can’t sign contracts, can’t do a lot of things, can’t smoke, can’t drink. “So with that said, I don’t think, as a country, we protect our children the way we should.”

Ellis said: “If a child commits harm, a child cannot be a mini adult — it’s still a child.”

It has been 20 years since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to sentence children to death. After the 2005 ruling, California, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont have abolished direct file laws. Currently, Pennsylvania, 11 other states, and Washington, D.C., continue to enforce them.

“Children [are being] sentenced to de facto life sentences and other extreme sentences, which are harsh,” said Ellis, who was 17 when he was convicted in 1991 in Washington D.C. for manslaughter, a crime he said he committed in self-defense. He was sentenced to 22 years.

Eliis, now 49, premiered his film Change is Possible in October. He also recently completed an ambassador program with Represent Justice, a nonprofit organization that uses storytelling campaigns to advocate change in the justice system.

”We believe that folks deserve a review, an opportunity of release, to prove why they should be home,” he said.

Since 2019, Democratic U.S. Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey has been advocating for the Second Look Act. The bill would allow people who have been federally incarcerated for at least 10 years to petition judges and have their growth and rehabilitation reviewed and their sentences reduced.

“Many of these individuals are serving excessive prison terms, are not a threat to the community, and are ready for re-entry, but they are stuck in overcrowded and costly prisons due to archaic sentencing laws,” Booker said in a press release when the bill was reintroduced in November. “These policies don’t make us any safer and waste valuable taxpayer dollars.”

Crime victim advocates argue that measures giving convicted people a second chance undermine the criminal justice system by invalidating the results of adjudicated cases, and are unfair to victims’ families.

Kimmi Herring of Safe Horizon, a nonprofit victim advocacy organization in New York City, said some families are strongly opposed to the idea of reducing sentences.

“I haven’t had any family that is totally satisfied with the sentence, much less thinking about the day that this person would be up for parole or granted clemency,” Herring said in a 2023 interview with Capital B.

How a juvenile case goes to adult court

The decision to transfer a young person’s criminal case to adult court is often at the discretion of the prosecutor. In many cases, depending on state law, this occurs without a hearing where the accused can present evidence of their character to a judge before being formally tried.

“Whenever you’re charged with a homicide, you’re immediately proceeded to adult court,” said Pace, who now serves as the senior reentry coordinator at the Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project. “They don’t view you from the perspective of a child, and it’s your responsibility — and your attorney’s responsibility — to try to convince the courts that you are amenable to treatment in a juvenile setting.”

Prior to his sentencing in 1985, Pace said, the only evidence provided by his attorney advocating for a lesser sentence was a single letter from a teacher. He said none of the letters from his 11 siblings or community members were given to the judge. Furthermore, Pace said, he and his parents were misled by poor legal advice, falsely believing that his sentence could be a maximum of 15 years in prison.

Pace, who said he believed he was taking responsibility for his actions, pleaded guilty to a second-degree murder charge. That charge carries a mandatory sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole.

As Pace’s 18th birthday passed and he prepared for his transfer to an adult prison, he was warned by youth facility counselors about the harsh conditions and the violence that was common in adult prisons.

“I was really concerned about it, like, what was really going to happen to me?” Pace said, recalling the stories he was told four decades ago. “That was my concern, like, how would I be able to survive the circumstances that I found myself in?”

“This is going to be, like, really hell — going to state prison.”

Since 2008, nearly 500 pieces of legislation have been introduced in 48 states to address the length of sentences for people under 18 convicted of a crime, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Pennsylvania’s Juvenile Justice Reform Task Force released its report in June 2021 that called to end direct file laws. But the state has seen little movement on the task force’s recommendations. A recently reintroduced bill calls for the state to change the sentencing guidelines for second-degree murder to a “more humane” option.

From life sentence to freedom

The early years of incarceration were vastly different for Ellis and Pace: While Ellis struggled to find empathy for taking another person’s life in self-defense, Pace was consumed by overwhelming remorse.

These feelings, Pace said, enabled him to look beyond his life sentence and became a “magnet for connecting to resources.”

“My goal: I wanted to change. I wanted to do things to demonstrate I’m not the person who committed this crime,” he said. Pace said he repented for being a “follower,” poured himself into education, and immersed himself in criminal law books to petition for a way out of prison.

Pace became known as a “jailhouse lawyer,” said Kempis “Ghani” Songster during a virtual screening of Pace’s film, Disrupted: Injustice, Trauma and Healing, a production of the Represent Justice Ambassador Program.

Songster, who first connected with Pace while incarcerated in Pennsylvania and is featured in Pace’s film, was sentenced to life without parole at 15 for murder. He served 31 years in prison before his release, and today is the co-founder of the Redemption Project.

The two men, who shared the same harsh fate, now meet outside prison walls, and said they are united in their advocacy for change. They even lead intergenerational healing circle meetings located mostly in the state.

After exhausting all of his appeals up to the state’s Supreme Court, Pace was finally able to foresee a release date in 2012. That was the year when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that mandatory life without the possibility of parole sentences for children under 18 were unconstitutional. This ruling was applied retroactively, providing a pathway to freedom for those like Pace and Songster, who had received sentences as minors.

By 2016, Pace’s sentence was reduced to time served, and he was released from prison the following year.

Ellis began his appeal process in the late 1990s. While reviewing his case files, he read the victim’s aunt’s impact statement to the judge. In her statement, Ellis said, he recalled that the victim’s aunt did not ask for the maximum sentence. Instead, he said she expressed empathy, acknowledging that he, too, was a child, despite the pain of losing her nephew.

“I began to have empathy for him [the victim] and think more about what I did, my actions, and accept responsibility for my actions,” he said. “And that was one of the moments where I started to mature more.”

Before Ellis was released from a federal prison in Colorado after 15 years, he said he started to surround himself with other “brothers who were fighting for what was right, who were growing,” despite most of them possibly never going home. He said he began reading, studying, meditating and praying, differently.

“But that moment of acceptance, despite him having a gun, I still can accept what I did that I wish it wouldn’t have happened,” Ellis said. “He deserved to live, just like I did.”

Great Job Christina Carrega & the Team @ Capital B News Source link for sharing this story.