Supreme Court lets Trump move forward with firing thousands of federal workers

April 8, 2025

“They Don’t Care About Civil Rights”: Trump’s Shuttering of DHS Oversight Arm Freezes 600 Cases, Imperils Human Rights

April 8, 2025This is the first in a two-part series on Central America’s history and present, featuring scholars Hilary Goodfriend and Jorge Cuéllar in conversation with Daniel Denvir on The Dig, a Jacobin Radio podcast. It is also a history of American near-empire, tracing its impact from the mid-nineteenth century onward.

Central America won independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821, spent two years as part of the Mexican Empire, and then nearly two decades as a fragmented federal republic. Its colonial economy was peripheral, based on self-subsistence and a small export trade in goods like indigo and cochineal. Independence brought political turmoil, with liberal and conservative elites warring while maintaining indigenous campesinos’ oppression.

By the mid-nineteenth century, US capital and military power reshaped the region. In the early 1850s, Nicaragua became an important transit point for Americans heading west to Gold Rush California. In 1855, a new railway built by American capitalists connected Panama’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts. That same year, American mercenary William Walker, invited by Nicaraguan liberals, seized power and legalized slavery. His rule ended when Central American armies forced him out, but his tenure demonstrated how Anglo-American ambitions treated local elites as expendable allies.

Meanwhile coffee production integrated Central America into global capitalism, fueling the rise of powerful oligarchies. American intervention in the region deepened: in 1885, the United States sent marines to Panama (then part of Colombia) to suppress a rebellion. The Monroe Doctrine, originally a warning against European meddling, became a pretext for American intervention. In 1903, the US backed Panama’s secession from Colombia to build the Panama Canal, securing control over the canal zone.

Bananas soon joined coffee as an economic driver, entrenching oligarchic rule and US influence. In 1909, the United States backed a successful effort to oust Nicaraguan ruler José Santos Zelaya, leading to two-decades of US occupation, a rebellion led by Augusto Sandino, the Somoza family dictatorship, and, ultimately, in 1979 the Sandinista Revolution.

In 1905, US president Theodore Roosevelt expanded the Monroe Doctrine, asserting the US’s right to intervene in Latin American countries to maintain “order.” The doctrine shored up American expansion, reinforcing imperial domination of the region.

By the early twentieth century, US intervention across the region was routine. A powerful American system controlled the Caribbean basin, though Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal–era Good Neighbor policy scaled back constant interference. During this lull, social democratic reforms flourished in Guatemala and Costa Rica. These reforms were a watershed, coming a decade after a communist and indigenous armed insurgency had been brutally crushed by the Salvadoran oligarchy in 1932.

Friendly American policy, however, abruptly ended with the onset of the Cold War. In 1954, the CIA launched a coup against Guatemala’s social democratic president, Jacobo Árbenz, for land reforms that threatened the United Fruit Company. This coup inaugurated an era of US-backed anti-communist, anti-indigenous terror in Guatemala. Political systems across the region grew more repressive, closing themselves off to even modest reforms as social and economic crises intensified. This in turn fueled armed revolutionary movements in Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador.

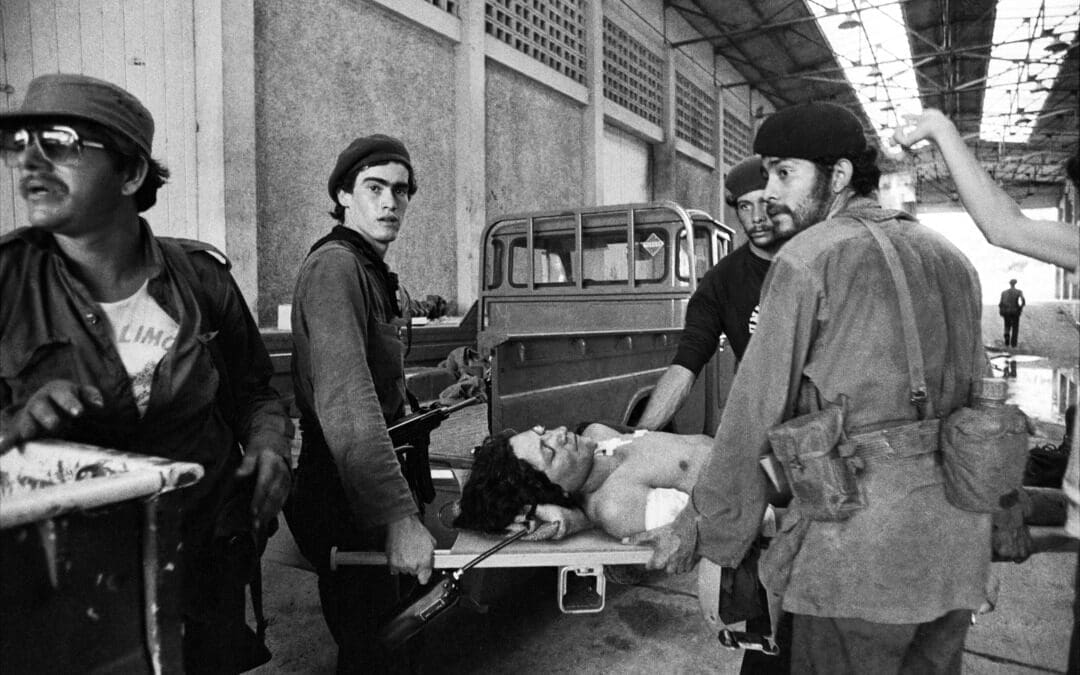

In Nicaragua, the Sandinista Revolution triumphed in 1979, only to be worn down by a US-backed insurgency based in neighboring Honduras. In Guatemala and El Salvador, the US-backed regimes fought off rebel armies by waging a murderous war against the people.

Central American history cannot be fully told in two episodes, let alone this introduction. What’s critical to understand is the direct line from US-backed military intervention to the support of reactionary oligarchies, the neoliberal restructuring of the postwar years, and the resulting devastation. The ongoing migration crisis is the most recent consequence — one now exploited as a tool in reactionary US politics.

Great Job Hilary Goodfriend & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.