A Truly Free Society Demands Workplace Democracy

March 14, 2025

Who’s Running the DOGE Wrecking Machine: The World’s Richest Man or a Little-Known Bureaucrat?

March 14, 2025

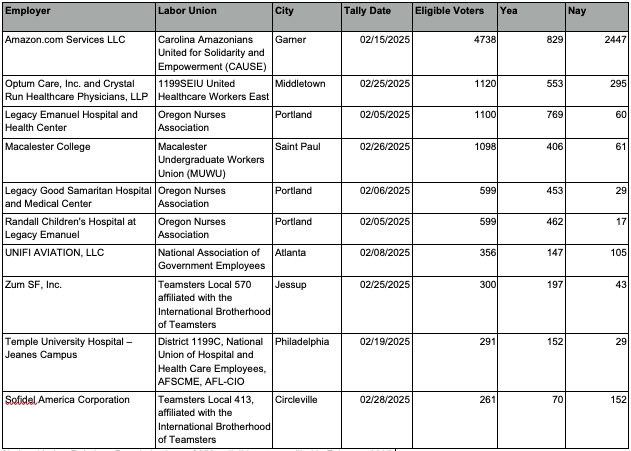

There were 122 National Labor Relations Board representation elections run in February 2025, and ten involved units of 250 or more eligible voters. Those ten elections, however, involved 74 percent of all eligible voters that month.

The highest-profile election was the loss at the Amazon Fulfillment Center in Garner, North Carolina, which my colleague Jonathan Rosenblum covers well here. Jonathan and I offer some more in-depth thoughts on what recent news in the world of Amazon organizing means in a recent article in these pages, but in brief: it’s going to be very difficult to make much headway with this company with traditional site-by-site organizing methods. Amazon is too big and too flexible for such organizing, and the company is only going to come to the table if the flow of goods through their dynamic distributional system is disrupted, which requires multisite coordination and a laser focus on the pain points in their facility network.

As with last month, health care elections dominated the large-unit news, claiming five of the eight large-unit victories. The other victories included an undergraduate workers’ union at Macalester College (1098 workers), transportation workers at Zum in Jessup, Maryland, joining Teamsters Local 570 (300 workers), and transportation workers at Unifi Aviation in Georgia doing the same with the National Association of Government Employees (356 workers).

The largest unit won in February was for 1,120 nonprofessional workers at an Optum Care subsidiary, Crystal Run Healthcare, a network of eleven primary care facilities in the state of New York. Optum is in turn owned by UnitedHealthcare, which gained massive international attention after the murder of its CEO, Brian Thompson, in December 2024 and is now the largest employer of doctors in the United States.

It’s worth repeating: the largest health insurance company in the country is also the largest employer of doctors. Amy Gladstein, assistant for strategic organizing at the union that organized Optum, 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, cited this “vertical integration of health care” as the driving force behind the organizing effort.

From the perspective of UnitedHealthcare, it makes sense to own the very primary care practices that they’re also reimbursing: cutting costs in the former means less expenditure in the latter. From both patients’ and workers’ perspectives, however, this vertical integration is extremely frustrating, depressing wages and benefits and depersonalizing care. And what’s happening at Optum is occurring in primary care across the country, from Amazon’s One Medical to Walgreens’s VillageMD.

One particular frustration felt by both workers and patients was the establishment of a call center: instead of getting direct lines to offices or departments, patients were directed to a general call center number where they would sometimes wait so long that they’d just give up on booking an appointment or doing follow-up. Some workers got in trouble when they’d give out direct lines or their personal numbers to patients.

As important as wages and benefits are to these workers, this basic breakdown in the provision of care was a key frustration for Optum workers. Gladstein noted that while the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were a primary source of organizing among hospital workers, it was frustrations like these, stemming from the corporatization of primary care, that fueled organizing efforts like that of Optum workers:

In hospital organizing, it was COVID and feeling unrecognized in staffing. In this organizing, it is the corporatization of health care. I think it comes from a different place. [Traditionally] if you’re working in a primary care practice, you know how to find the doctor, and the doctor isn’t being squeezed into twenty-minute blocks. And then, all of a sudden, you’re under this other set of rules, and [they’re written by] a big corporation that makes billions. So it’s a different set of issues that draw people toward us.

Optum has run an intense anti-union campaign and even has an in-house, anti-union management team euphemistically dubbed “the People Team.” After the successful representation election, where the union won by a two-to-one margin, Optum announced its intention to challenge the results, on the grounds that 1) since the NLRB did not have quorum, it could not certify elections and 2) that the company was not able to exercise its free speech rights by holding captive audience meetings, which were banned in the waning days of Joe Biden’s NLRB.

The first objection, now made irrelevant by the fact that Gwynne Wilcox has been reinstated as an NLRB board member, never held up, as the board has the ability to process elections at the regional level even while lacking the ability to decide cases, according to a 2010 Supreme Court case. The second objection, that depriving a company of the ability to hold mandatory meetings is an infringement upon its free speech rights, is about as twisted an understanding of the First Amendment as you’re going to find.

The Oregon Nurses Association (ONA) won three large units at the Legacy hospital system in Portland, Oregon, totaling 2,298 nurses. ONA actually filed for these units together, and the board stipulated that the elections be run separately, so arguably this was the de facto largest unit won in February.

Elizabeth Gemeroy, deputy director of organizing at ONA, cited the alleged normalization of practices during the COVID-19 pandemic as a key spur to organizing:

COVID really just exacerbated all issues in health care. During COVID, staffing [i.e., the staffing ratios of number of nurses to number of patients] was horrible, because we were trying to stop the spread. All of the protections went away because we were in a crisis situation. And management was like, “Oh, we made a lot more money when we were in crisis, because there were a lot more people who came into the hospital and a lot fewer staff.” And it seems like that’s now the model.

As with Optum workers, Legacy nurses also felt the impingements of the corporatization of health care:

There was a huge lack of transparency from their employer. This is a trend with the corporatization of health care: there’s so many managers, and your direct manager working on the floor [is answering to someone else] who’s making decisions about patient care, [and they’re] not even in the hospital. They’re probably states away. They probably have a degree in business, and they’re generally making decisions based on spreadsheets, not based on patient care, patient outcomes, or best practices.

This alleged lack of transparency was also felt in pay disparities and what many nurses felt to be a lack of recognition of seniority. More generally, knowing what their equivalents made at other hospitals, nurses at the Legacy hospitals simply felt they were underpaid as a whole.

The organizing drive started with the formation of Legacy Frontline Workers, a grassroots group that started a petition against Legacy’s COVID practices in 2021. ONA started working with three different groups of workers at the three different facilities at that time, but eventually they ended up combining organizing committees, as nurses from different hospitals were happy to work together as part of a broader effort. This proved a fortuitous decision when it was announced in October 2024 that the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) bought Legacy’s facilities. ONA already had a strong foothold at OHSU hospitals, whereas Legacy had been much more hostile to unionization.

This announcement energized the organizing efforts, and all three facilities filed for an election at the same time. According to Gemeroy, the units made a conscious decision to wait until all three were ready to file, understanding the importance of the solidarity that had been built through the system-wide organizing committee.

ONA has a set program for building organizing committees and ensuring wins in NLRB elections, executed in collaboration with nurse leaders. But Gemeroy said that they slightly changed their practices to accommodate such a large unit of workers. Typically, they would hope to form an organizing committee comprising roughly 10 percent of the total unit, achieving a leader-to-worker ratio of one to ten. In this case, that would have meant an organizing committee of about 230 workers. To maintain a tenable decision-making body, they kept the organizing committee around seventy nurses and trained an additional layer of about 140 nurse organizers to be election captains, thus allowing for an extension of organizing structure without impeding decision-making.

Both Gladstein and Gemeroy were concerned about larger political dynamics around looming disruptions to the NLRB process but didn’t feel like they were going to impede new organizing efforts. If anything, Gemeroy believes that a more hostile political environment will “invigorate more folks to move to organizing.” The February total election count was not out of line with that of previous years, so any cooling of labor organizing interest with the new Trump administration has yet to be registered.

Great Job Benjamin Y. Fong & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.