Report Exposes Musk Operatives Who Have Infiltrated Social Security Agency | Common Dreams

March 14, 2025

Sebastiano Timpanaro Lived His Life With the Italian Left

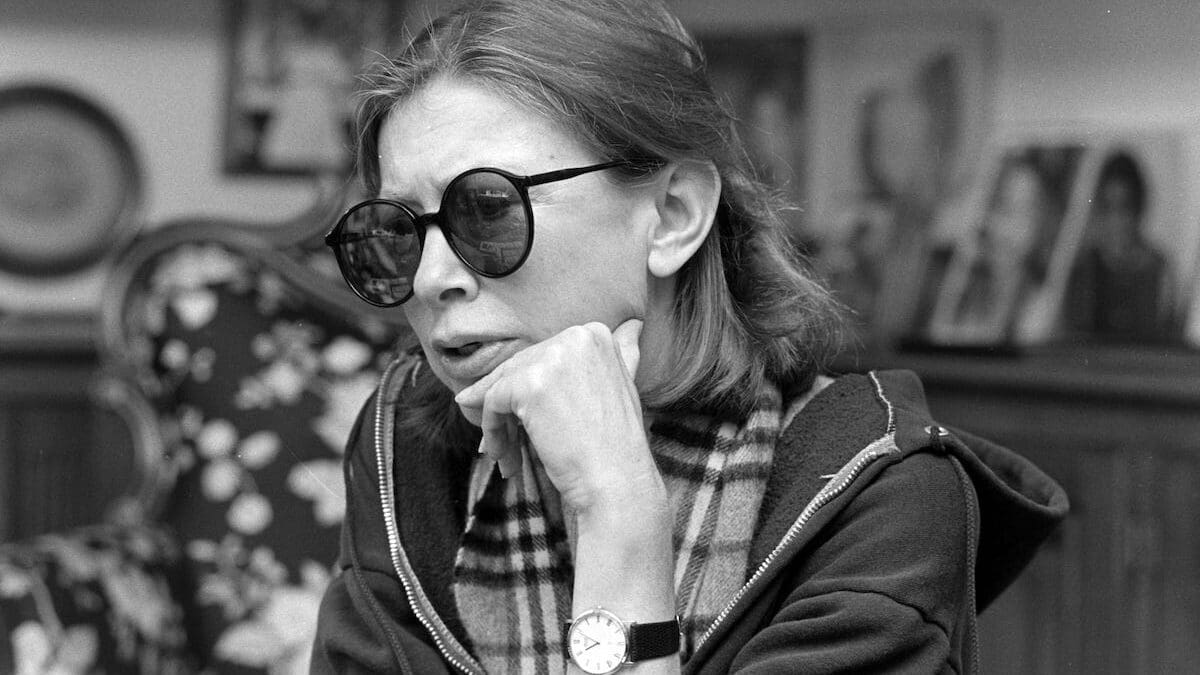

March 14, 2025Joan Didion’s time as a film critic comes up for discussion in Alissa Wilkinson’s new book on the essayist, We Tell Ourselves Stories. Needless to say, I’m fascinated by this segment of her career for predictably selfish reasons—we are narcissists, all of us—and was sad to see confirmed something I had suspected but not known for sure: that her criticism has never been properly collected, for some reason. But it was particularly illuminating to see how one of our greatest essayists approached the job, at least in part because it is clear her critical ethos overlapped with her impulses as an essayist, and a nice reminder of a time when cultural writing in political journals was somewhat more elevated than it tends to be now.

For a time, Didion was a critic at National Review, a posting in line with her youthful, Western U.S. conservatism. “In founding the magazine, William F. Buckley Jr. had realized that to be taken seriously among the other magazines and journals of the time, he’d need a crackling set of writers to explore, in particular, the culture,” Wilkinson writes. Needless to say, Didion fit this mandate; few typewriters crackled louder than hers. But she wasn’t interested solely in dogma or politics; rather, “she’s interested in the people and the reasons they love or hate the product, sometimes more than the product itself.”

Understanding why a piece of art works—and perhaps even more importantly, accepting that it works and knowing who it works for even if you don’t quite understand why it works—is, I think, a fairly key critical function. Part of that revolves around having some idea of how the business of showbiz works: “Her tastes weren’t populist, but they weren’t snobbish, either; one reason few people realize that Didion worked for years as a film critic before beginning a career as a screenwriter may simply be that her criticism is short, punchy, and more preoccupied with the business and aura of the Hollywood star machine than arguments about film as art.” (This is also, likely, a reason she was so good at covering the world of politics as it devolved into a funhouse mirror of the entertainment industry.)

While Didion would occasionally touch on politics in her reviews (Wilkinson recounts the essayist’s annoyance with a group of Kennedy-Democrat Esquire writers snickering at John Wayne’s The Alamo, a film that moved her to tears), she avoided getting sucked into the culture-war silliness that so dominates, in some way defines, so much of modern film writing.

A brief digression: When our podcast Across the Movie Aisle was initially formulated way back in the dark days of 2020, the “controversy or nontroversy” segment was intended to address a different culture-war idiocy each week, some stupidity that bubbled up on Twitter or in the political mags, and we would settle whether it was a, well, you get it. The segment shifted in relatively short order to focus more on the business side of things (it’s why we’ve done so many episodes on AI, streaming, etc.) because I quickly realized I would rather die than spend my time adjudicating all these episodes. Is the new Snow White doomed because Rachel Zegler said something dumb about the original cartoon or because antisemites are mad that Gal Gadot stars in the film? I dunno, maybe. Alternately, none of these things might matter at all and it could still clean up at the box office because there is a real paucity of family fare at the multiplex. Ultimately, the structural forces matter more than whatever anyone’s mad about on any given day, and while it’s good for clicks to declare that art is suffering at the hands of the wicked for their bad political ideas, it’s rarely edifying.

Frankly, this is why on this week’s segment about Star Wars and Kathleen Kennedy I simply glossed over the critiques of her pushing the idea that “the Force is female.” It has to be mentioned if you want to understand why some people are mad at her, but, to my mind, it’s one of the least important reasons why she has struggled in the years following the early triumphs of The Force Awakens and Rogue One. I don’t think we have great data on whether or not the push to increase female representation in the Star Wars fanbase has been successful or not, but we do have lots of data on projects that were announced and then killed, or produced and then heavily monkeyed with after shooting ended. And those are all executive-level problems.

Anyway, I would love it if someone could collect Didion’s film criticism, if only to get a better sense of Didion’s sense of how people in the moment were responding to the films of the moment.

At one point in Opus, Ariel Ecton (Ayo Edebiri) is complaining to Kent (Young Mazino) that here she is, 27 years old (quelle horreur), completely unaccomplished. Sure, she works for a big-time music magazine; yes, she’s making it work in New York City. But she hasn’t written much of anything. Nothing of major importance. Her crisis was sparked by her boss, Murray (Stan Sullivan), loving a pitch only to immediately assign it to a bigger name, a better writer.

And Kent tells her, not without compassion but probably more nakedly than he should have, that she doesn’t really bring much to the table. “It’s perspectives that give opinions their value,” he says, but she has none. She’s not rich, she’s not poor; her family is unexceptional; her life story is … uncompelling. “You’re middle as fuck.” As we know, there’s nothing worse than being mid. Mushy midness: that’s personal and professional death.

So it is with some surprise—to her, to her coworkers—that Ariel is asked by the mysterious, reclusive pop star Moretti (John Malkovich) to accompany Murray to Moretti’s compound to listen to his first studio album in 27 years. Ariel and Murray will be joined by vapid influencer Emily Katz (Stephanie Suganami), grating television personality Clara Armstrong (Juliette Lewis), rock critic and podcaster Bill Lotto (Mark Sivertsen), and paparazzo Bianca Tyson (Melissa Chambers) on this visit, where they are supposed to luxuriate in Moretti’s presence and learn the tenets of Levelism.

Needless to say, things get weird, as cults of personality collapse into actual cults out in the middle of nowhere. By the end of the film, Ariel will have the lived experience necessary to do the thing she’s always wanted (write a bestselling work and become the subject of interviews herself). She transcends her midness, experiences a moment of genius. But at what cost?

Opus works best in individual, discrete moments, as when cultist Belle (Amber Midthunder)—who has been tasked with keeping an eye on Ariel at all times—tries to discreetly follow her on a jog through the compound. There’s just something very funny about the visual comedy of it, the running, then not running, the shoving hands into pockets and noticeably looking away. It’s a solid piece of visual comedy, and there are several laugh-out-loud moments. (You know you’re in for a good time when Tony Hale shows up in a bit part, and his bit part here as Moretti’s hype man is absolutely brilliant.)

Strictly on a performance level, Opus is tremendously watchable; the choices made here by the actors and writer-director Mark Anthony Green are spot-on, finely walking the line between absurd and terrifying. (Malkovich occasionally tumbles well over the line of absurd, but this is intentional; the ridiculousness of his persona and the horrendousness of his music is, I’m sure, part of the bit. That this goober would inspire cult-like devotion is a good gag.)

I loved watching them work; I’m not entirely sure the film hangs together. Opus occasionally feels at war with itself. The utter banality of a junket is a great setting for a torture sequence, but the revulsion with that process (which I fully empathize with; there’s nothing worse than a bad roundtable Q&A) is tinged with just enough venom to undercut the grotesquerie of the proceedings. Victims need not be entirely sympathetic, but it’s hard to make a sequence like this work if we don’t know why they deserve their fate.

Still, Opus is interesting, amusing in an off-kilter way, and meanspirited in a way that I’m always up for. Plus, anytime you get to watch John Malkovich vamp for 107 minutes, you jump at that chance. Even if it devolves into murderous mayhem.

Great Job Sonny Bunch & the Team @ The Bulwark Source link for sharing this story.