Sanders Warns Musk’s Call for $700 Billion in Cuts Is a ‘Prelude’ to Social Security Privatization | Common Dreams

March 11, 2025

A Tale of Two Bigots

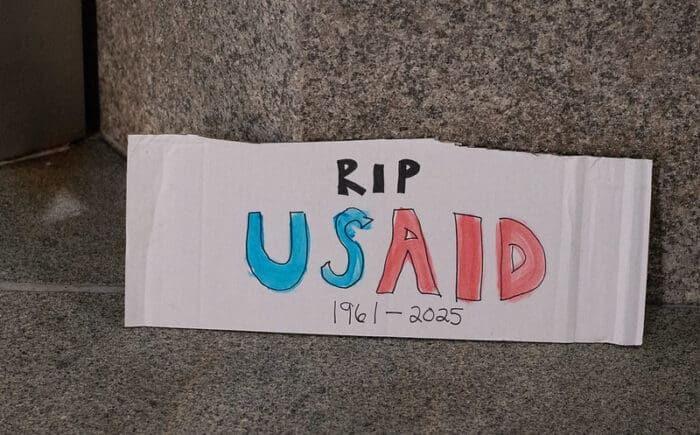

March 11, 2025Wendy Monterrosa and her colleagues founded news site Voz Pública in El Salvador in 2020. A year into Nayib Bukele’s presidency, marked by frequent attacks on journalists, Voz Pública built a small newsroom focused on fact-checking and investigative journalism. But everything crashed down in early February when Donald Trump put on hold any funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). [Ed. note: On Monday, a U.S. district judge ordered the Trump administration to pay nearly $2 billion in foreign assistance that Congress had already authorized.]

USAID accounted for 70% of Voz Pública’s budget. So Monterrosa and her colleagues were forced to reduce their newsroom from six full-time journalists to just three, along with two other part-time colleagues. Investigative projects were slashed and fact-checking efforts severely reduced. “We are going through an uphill battle now,” she said. “But it’s not just us: other outlets in El Salvador are facing a similar threat.”

The USAID cuts have impacted hundreds of outlets in places where public interest journalism is chronically underfunded and often under attack.

Before Trump’s inauguration, the U.S. government supported independent journalism in more than 30 countries. Most of this funding was channelled through USAID. According to a USAID factsheet recently mentioned by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and now taken offline, the agency funded training and support for 6,200 journalists and assisted 707 outlets.

According to RSF, this annual media budget was $268 million. This sum accounted for 0.004% of the U.S. government’s total annual budget and was around half of government funding for public interest journalism around the world.

A perfect storm

The freeze of USAID funding is the most recent blow for donor-funded journalism, but not the only one. The National Endowment for Democracy, an organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1983, is now unable to access its own funds and has been forced to suspend support for nearly 2,000 partners worldwide.

Earlier this year Meta announced the end of its U.S. fact-checking program and many fear the company will soon withdraw funding from its partners in other countries too.

Funding from American philanthropic organizations is also drying up. According to four sources consulted for this piece, the Open Society Foundations (OSF), which funded dozens of independent news organizations for many years, won’t be funding them from now on.

Experts now fear that other American foundations follow suit and redirect some of their funding to newsrooms inside the country or entirely away from journalism to cover for cuts in healthcare projects or scientific research. Even governments like the U.K., Norway, or Germany, which have funded independent media in the past, may retreat from the field as they cut their foreign aid budgets to ramp up defense spending in the face of geopolitical risks.

This is a perfect storm for hundreds of news organizations. So we spoke to 15 journalists, editors, and experts on media development from a dozen countries to learn how these changes are impacting public interest journalism in different regions, how authoritarian leaders are benefitting, and how news organizations can find ways to survive.

A Colombian news site under pressure

The hardest hit by these cuts are smaller outlets in fragile democracies. But larger organizations in more stable countries are suffering the impact too.

A good example is La Silla Vacía, a news site founded in Colombia by award-winning journalist Juanita León in 2009. Around 9% of the site’s budget comes from USAID. A further 30% comes from Meta’s fact-checking program and is likely to end by the end of this year.

“Meta’s funding is one-third of our payroll,” León said. “So I’ve had to lay off seven of our 40 journalists. Now we’ll need to cut back the number of stories we publish and stop covering the cities of Bogotá and Cali. We’ll need to change the way we work.”

La Silla Vacía is not a small news startup. The outlet has been around for 15 years, has won several important awards, and is one of the most influential newspapers in Colombia. Since its launch, it has received grants from organizations such as OSF, the Ford Foundation, the Nature Conservancy, the British government, and the World Bank. Now León fears Trump’s cuts will create a domino effect, with some of those entities retreating from journalism and focusing on other areas.

USAID helped La Silla Vacía fund its coverage of the Amazon region and supported a transparency initiative that covered the salaries of its investigative team. “This project also funded a few hyperlocal newsrooms in places like Barranquilla and Ibagüé,” León said. “This is going to be terrible for those outlets as USAID covered a huge part of their budgets. I’m not sure they will survive this.”

Colombia is holding an important election in 2026 and León is now trying to ensure her outlet gets enough funding to report on it. She doesn’t want her budget to depend on a few big businesses and she doesn’t want to set up a paywall: “I see so much misinformation spreading on social media that I just don’t see the point. I see the work we do as a public good.”

León thinks journalism is now facing an existential crisis on many fronts. “It’s not just funding,” she said. “Our distribution depends on tech companies and generative AI may make things even worse. Audiences get depressed and don’t want to follow the news. I often feel as if we were the violinists in the Titanic. But the band will play on for now.”

How will this impact journalism in Central America?

Central America is one of the most vulnerable regions to the latest cuts. “It is a poor area where institutions are weak and where journalism is already under attack,” said our Chilean alumna Francisca Skoknic, who spent her time in Oxford writing this project on donor-funded journalism in Latin America. “News organizations in these countries are even more dependent on international funding than those in other regions, and someone is going to have to fill that void.”

No one knows donor-funded journalism in Latin America better than Colombian journalist María Teresa Ronderos, who led the OSF journalism program for four years and is now the editor-in-chief of CLIP, an investigative outlet that partners with outlets across the region.

Ronderos is deeply concerned about smaller newsrooms in Central America. “These are the bravest, most independent outlets in each country,” she said. “They are those holding power to account and those investigating abuses of power from any government left and right. Those people really need philanthropic funding. There is no other way they can survive.”

The kind of money these outlets would need is pretty small, Ronderos said. Funding from donors provided them with “a certain safety net,” which they complemented with revenue from memberships, advertising, training or digital services.

Journalists are under pressure in almost every country in the region. In El Salvador, President Bukele often slams independent journalists and presents them as “part of a worldwide money laundering operation.” In Guatemala and Honduras, reporters are frequently targeted with strategic litigation. In Nicaragua, ranked 163 out of 180 in RSF’s Press Freedom Index, journalists have been forced to flee and work in exile.

Nicaraguan news site Divergentes received funds from USAID between 2020 and 2022. From exile, its editor-in-chief Néstor Arce said that they are concerned about the uncertainty around foreign donors, even if they are not affected by the current cuts. “We don’t know if our other grants will be renewed,” he said. “If they are not, we will have to drastically reduce the number of people who write for us.”

Plaza Pública, a news site from neighboring Guatemala, has lost 20% of its budget as a result of USAID’s freeze. Its editor Francisco Rodríguez said they are luckier than others as they are mostly funded by the Rafael Landívar University.

They haven’t been forced to lay off any journalists yet, but they’ve had to cancel some reporting projects focused on migration. What Rodríguez fears the most, though, is that these funding problems create a tougher environment for independent journalism in the region.

“I fear we get to a point when there are no other independent news organizations in Guatemala,” he said. “I trust my colleagues and the ability they have to stand up. But if these pressures continue, some outlets may start to disappear.”

Jennifer Ávila, editor-in-chief of the Honduran outlet Contracorriente, is also worried about the recent cuts. While her outlet has not received any funding from the American government, around 80% of their budget comes from foreign foundations and nonprofits.

During our conversation, Ávila mentioned OSF’s withdrawal from journalism as a factor that has made things difficult for many journalists in the region and fears that U.S.-based nonprofits shift their strategy to focus on journalism in their own country.

“I’m worried, but this is not new,” Avila said. “Those of us who’ve decided to do investigative journalism have never been calm. We are always going through a crisis. But we have learned to be creative to survive.”

Will Ukraine’s press survive these cuts?

The USAID cuts have affected many outlets in Central and Eastern Europe. “This change will disproportionately affect local and investigative nonprofits, especially those dedicated to public-interest journalism and serving underserved communities,” explains our Hungarian alumnus Peter Erdelyi, who writes this weekly newsletter on media funding and spent his time with us analyzing reader revenue models. He now works at the Center for Sustainable Media, an organization helping independent publishers in the region.

“By their nature, markets do not efficiently distribute public goods,” he said. “Providing reliable information to small communities, reporting on poverty, or covering controversial stories is rarely profitable. The very people who benefit the most from this kind of journalism often lack the resources to fund it. And because these communities face economic hardship, advertisers are unlikely to invest in media that highlights these struggles. As a result, these newsrooms have relied on grants and institutional funding and that support is now disappearing.”

Publishers in places like Serbia and Hungary are already feeling the consequences: talented journalists are being laid off, newsrooms are scaling back their coverage, and reporters are forced to seek additional jobs to sustain their families.

In the long term, Erdelyi envisioned several possible scenarios: “Some countries receive funding through the EEA Grants, primarily backed by Norway,” he said. “These programs are set to launch in the third or fourth quarter of this year and may offset some of the financial losses. The EU also offers funding schemes and some private philanthropic funding could help fill gaps. In this optimistic scenario, some losses may only be temporary. But the U.S. government is not the only major player pulling back. So this could trigger a domino effect, with even more funders stepping back. In a pessimistic scenario, the current losses are permanent and they mark the beginning of a prolonged period of financial scarcity.”

No country has been hit so hard by the current cuts as Ukraine, where the most vulnerable outlets are small, independent outlets operating close to the frontlines, said Andrey Boborykin, CEO of Ukrainska Pravda and head of growth for the Media Development Foundation (MDF), a media hub helping local newsrooms across Ukraine develop their business models.

Ukrainska Pravda is not as affected as other outlets. According to Boborykin, up to 75% of its revenue comes from commercial sources, including advertising revenue, reader revenue and commercial events. But up to 30% of Ukrainska Pravda’s revenue does come from donors and over half of that comes from USAID.

Many of the local publishers Boborykin is in contact with through MDF are in a tougher spot, with 50% to 75% of their budgets funded by USAID grants. European-based donors are not responding fast enough, said Boborykin, who pointed to bureaucracy and institutional fatigue after three years of wartime as possible reasons.

The hardest hit newsrooms are those operating in places under frequent Russian attacks. These outlets don’t have a viable advertising market and it’s almost impossible for them to get any reader revenue.

Boborykin fears Ukraine’s media landscape goes back to the mid-2000s. If independent publishers have to shut down, the void would likely be filled by local politicians, oligarchs and businesses starting publications to defend their interests, he said. An election will increase the chances of Kremlin interference. “Elections are a ripe environment for corrupting the media,” Boborykin said.

The outlook looks especially bleak for local news. “If there is no U.S.-backed media development funding and if the EU funds for media stay at the current level, most of the independent local publishers will have to cut spending and fire people, and a significant number of them will have to shut down,” Boborykin said.

How will this impact investigative journalism?

Investigative journalism is expensive. It often involves traveling, using expensive software, and spending months on a single story. In some countries this work can’t be funded by legacy news organizations, as they are often too close to businesses and politicians. So it often depends on access to grants from foundations and government agencies.

A good example of this model is the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), a global network of investigative journalists. The network’s initial focus was Eastern Europe, but it later expanded to collaborate with partners around the world.

Before this year’s freeze, U.S. government funding amounted to 38% of OCCRP’s total budget, around $7 million in the last year. This included money from USAID as well as other U.S. government initiatives.

This dependence was highlighted in a piece recently published by Mediapart. The article claimed that OCCRP had hidden the extent of its links with the US government and that U.S. public officials could veto its senior staff. OCCRP’s editor-in-chief Miranda Patrucic responded by requesting corrections to the article, arguing the organization is transparent about its funding and its editorial policies. Mediapart refused to amend the piece.

OCCRP publisher Drew Sullivan recently told us the organization will survive despite the USAID freeze. He said that the rest of their funding is diversified and explained they are already fundraising in Europe.

But Sullivan expressed concern for some of OCCRP’s partner organizations. Up to 82% of the subgrants aimed at news organizations partnering with OCCRP were cut. Almost all funding to the organization’s 71 local member centers also ceased to exist.

“Journalists working around the world are at great risk,” Sullivan said. “Some might lose work visas and be forced to go back to countries where they will be arrested. Many are losing help from the organizations that provide them with physical and digital protection.”

South African journalist Beauregard Tromp, who was OCCRP Africa editor until last November, said that the USAID freeze has not impacted African outlets so much as those in other latitudes. But most organizations, he said, do rely on foreign funding coming from donor organizations.

“I tend to look at this as an opportunity to reshape how we go about our funding models,” he said. “We are used to these kinds of struggles.”

Nigerian journalist Oluwamayowa Tijani, who is the director of projects for online newspaper The Cable is less optimistic. With the departure of the U.S. and the U.K. from the foreign aid space, Tijani doesn’t know who will step up to fill the gaps in the wider media ecosystem in Africa.

“It’s all about ‘Me first’: America first, the U.K. security first. That worries me more than what individual organizations would do,” he said. “Certain organizations are even beginning to consider the possibility of getting funding from China or Russia. That’s concerning.”

How are autocrats using the USAID cuts to attack journalists?

Authoritarian leaders often use the presence of “foreign donors” as an excuse to discredit independent journalism. Nicaragua presents a clear example of this.

In 2020, the government passed a foreign agents law requiring any Nicaraguan citizen working for “governments, companies, foundations, or foreign organizations” to register with the government, report monthly their income and spending, and provide prior notice of what the foreign funds will be spent on.

This law, which has been adopted in different forms by many other authoritarian countries, allowed Ortega’s regime to monitor the finances of independent news organizations supported by foreign benefactors.

Most independent newsrooms in Nicaragua are now forced to operate from exile. Independent media inside the country are practically non-existent as a result of the intense wave of repression by the regime.

Néstor Arce, the journalist from Divergentes, has seen first hand this discrediting of journalism based on who helps fund it. The regime sees enemies everywhere, from the United States government and OSF to Christian nonprofits.

“There are all kinds of organizations funding journalism, but this does not compromise our editorial independence,” he said. “Since we founded Divergentes in 2020, no one has told us what to cover or not to cover.”

El Salvador’s President Bukele applies a similar playbook. Monterrosa, the founder of Voz Pública, is concerned about the impact of this rhetoric at this critical time. “This has happened before,” she said. “Bukele accused our colleagues of El Faro of money laundering and then the government acted against them.”

This incident happened in 2023, when El Faro was audited for tax evasion, an accusation the outlet’s owners vehemently deny. After this, El Faro’s administrative operations were moved to Costa Rica to avoid further constraints.

As a way to protect their editorial independence, Voz Pública recently partnered with 11 other independent outlets. They launched a public campaign and started working together to make sure no outlet is left behind.

Tromp, who’s now the convenor for the African Investigative Journalism Conference and the head of the African Investigative Journalism Network, said that the potential of attacks by government officials is one of the reasons why African outlets have been so reluctant to take aid from the U.S. “People are concerned they’d be accused of being a U.S. puppet or working for the CIA,” he said.

Drew Sullivan, OCCRP’s publisher, recently touched on this point on a LinkedIn post: “It’s not just political interests but organized crime, businesses, enablers, and other journalists who regularly attack us. What’s common in all of these attacks is that the truth doesn’t matter and it will not protect you. Few attack the facts in our reporting. OCCRP prides itself on being independent and nonpartisan. No donor has any say in our reporting.”

Some of the outlets affected by the cuts prefer not to launch a fundraising drive right now, as this would make them even more vulnerable to fresh attacks from influencers and government officials.

Some attacks even extend beyond the online sphere. Earlier this year Serbian authorities conducted a raid on the premises of the Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability which runs the Serbian fact-checking platform Istinomer, citing unverified allegations of corruption involving USAID funds.

“This is not the first time that government institutions in Serbia have attempted to intimidate independent media, but it is an unprecedented escalation of government repression, meant to silence independent voices,” said the International Fact-Checking Organization in a statement about the raid.

What’s next for the outlets hit by these cuts?

Most of the outlets contacted for this piece acknowledge that relying on foreign aid is not a sustainable business model and many are exploring new income sources, including reader revenue.

South African investigative journalist Tromp stressed that it’s difficult to implement subscription models in the African context. But he thinks outlets should look at those peers who have managed to get funding beyond the rat race of chasing foreign grants.

“It’s not particularly useful to copy and paste models from the Northern Hemisphere,” he said. “The models we find most useful are those of our colleagues in Latin America and South Asia. This kind of South-South engagement matters.” Tromp’s suggestions include bundle events, subscriptions via corporate partners and micropayments.

As an expert on media revenue, our former Journalist Fellow Peter Erdelyi thinks the news publishers affected should be realistic. They shouldn’t delay tough decisions, as this could make things much worse down the road. He thinks newsrooms should launch fundraising drives as soon as possible: “You can’t sound the alarm every month, but if this is a genuine emergency, be upfront about it. Honesty and transparency are key: clearly explain the stakes, set a realistic fundraising goal, and ask your readers, viewers, or listeners for help.”

Erdelyi stressed that newsrooms may need to revisit past decisions about their revenue models, for example including events or advertising in the mix. “There is no shame in adjusting your approach,” he advised. “As long as you’re transparent, your audience will likely understand and appreciate your efforts to stay afloat. Consider what other valuable services your newsroom can offer. Do you have expertise in filing freedom of information requests, using AI tools to analyse data, or creating compelling visualizations? Journalists possess a wide range of skills that are useful in other sectors. There may be opportunities to leverage this knowledge as a new revenue stream.”

Institutional funding will be increasingly difficult to secure, as competition for limited resources intensifies. So anyone reaching out to major funders will need a solid plan. “Those large donors will certainly require more than just a plea for support,” Erdelyi said. “You need to demonstrate how your work aligns with their priorities and show that you have a sustainable strategy beyond simply replacing one funding source with another.”

He also thinks newsrooms shouldn’t be afraid to rethink their editorial structure, their formats, or their output volume. “If your survival is at stake,” he said, “this is the time for bold experimentation. As long as you’re honest with your audience about the changes, they will be more likely to support you through the transition. The alternative, shutting down entirely, is far worse.”

Colombian journalist Ronderos also sees the current crisis as an opportunity for journalists to rethink what they do. “Colombia is a great example,” she said. “Every journalist creates their own news site and it’s impossible to get funding for all of them. I hope journalists come together and forge alliances to get through this difficult moment.”

Ronderos encourages those billionaires in Colombia and elsewhere who believe in protecting liberal democracy to step in and support news organizations through intermediaries such as BBC Media Action and IFPIM. “Many of these people are as terrified as we are and appreciate the role of news organizations in holding power to account,” she said. “Look at what happened in Brazil: democracy wouldn’t have survived without the work of the news media and civil society.”

Is it possible to convince the current U.S. administration to reconsider its position? Ronderos is not optimistic, but makes a strong argument for unfreezing USAID media funding.

“Trump says he cares about immigration, money laundering, and organized crime,” she said. “It doesn’t make any sense to withdraw funding from news organizations that are reporting on these issues. If Trump wants to protect Americans, he should be increasing media funding, not ending it.”

Great Job Gretel Kahn & the Team @ Nieman Lab Source link for sharing this story.