SNL At 50

February 22, 2025

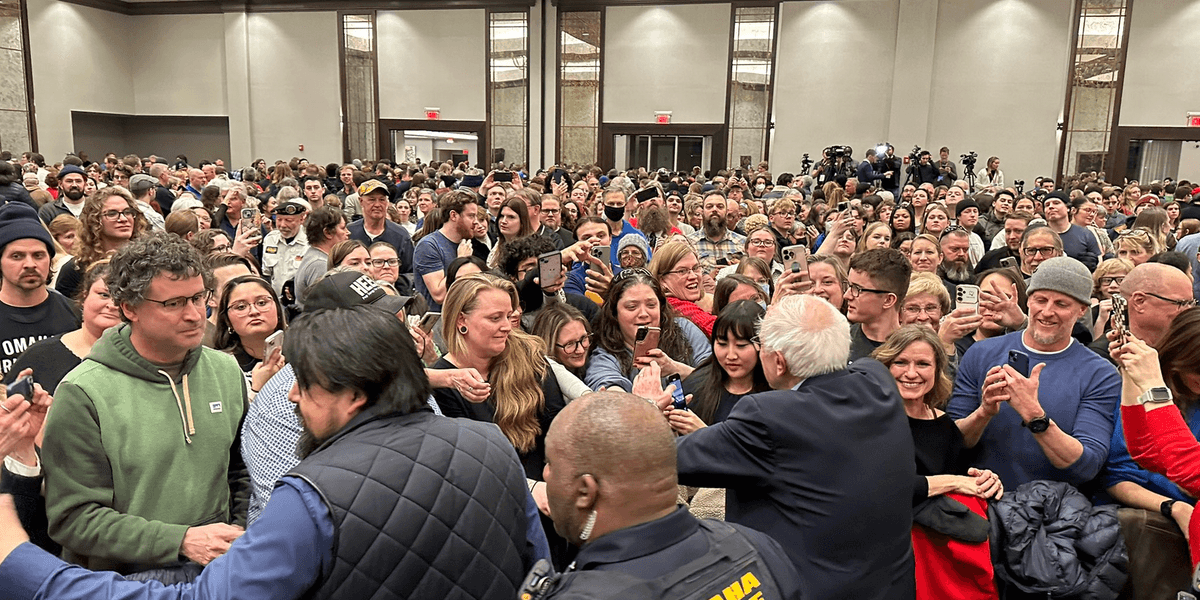

Thousands in Midwestern GOP Districts Attend Sanders’ First Stops on Tour to Fight Oligarchy | Common Dreams

February 22, 2025

The last fifteen years have seen tremendous political upheaval in Central America. El Salvador has fallen under a repressive, authoritarian regime, while Honduras has liberated itself from one; President Daniel Ortega has increasingly isolated himself from former Sandinista allies in Nicaragua; and in Guatemala, a popular tide of outrage against an entrenched ruling class saw an unlikely social democrat take the presidency.

Amid de facto dictatorships, besieged reformers, and popular demands for change, the political infrastructure installed as part of Central America’s postwar transition in the 1990s has broadly lost legitimacy. This liberal exhaustion is indicative of a deeper crisis, that of the isthmus’s postwar neoliberal political economy — which, like neoliberalism globally, has sputtered and stalled. In what follows, I explore this crisis through the lens of recent political events in El Salvador and Guatemala. To do so, I begin with the transition to democracy that followed the defeat of the region’s revolutionary movements in the 1990s.

For decades in the late twentieth century — thirty-six years in the case of Guatemala — the republics of Central America were rocked by brutal civil wars between US-backed anticommunist military regimes and national liberation armies fighting to free the isthmus’s impoverished majorities from oligarchic oppression and imperialist intervention. In the 1990s, however, the region began transitioning out of dictatorship toward liberal democracy and neoliberal accumulation. In Nicaragua, the 1979 Sandinista revolution was followed by a bloody, decade-long US-backed paramilitary “Contra War” against the new government, finally forcing a 1990 election that saw the Sandinistas lose power. In El Salvador and Guatemala, peace agreements brokered an end to national liberation struggles in 1992 and 1996, respectively.

As historian Greg Grandin observes, “Latin America’s move away from military dictatorships in the 1980s was less a transition than it was a conversion to a particular definition of democracy.” From a broadly conceived demand for self-determination, equitable economic development, and social welfare, democracy was reduced to a legal matter of political rights and market freedoms. In 1988, Franz Hinkelammert saw early on that the democratic transition was, essentially, a euphemism for structural adjustment. Together with the “Washington Consensus” of policy prescriptions for privatization, deregulation, and trade liberalization, democracy became “a packet of measures to apply.” Under the paradigm imposed by the United States, its attendant international financial instruments of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and local elites who stood to benefit from the restructuring, it is “business and the market [that] produce freedom, and democracy administers it.” This new, technocratic right was to discard its fascistic death squads and dictatorship in favor of the steely pragmatism of capital.

In El Salvador and Guatemala, the managed transition after the decades of state atrocities was carried out through a “truth and reconciliation” model framed on the one debuted in the Southern Cone in the early 1980s to put an end to that region’s guerilla movements and bloody, US-backed counterrevolutionary campaigns at the hands of ruthless military dictatorships. Grandin charts how the first truth commissions in Bolivia and Argentina had intended to lead to prosecutions of officials who perpetrated the worst atrocities. Yet with the revolutionary movements defeated, the military victors of those counterinsurgency wars retained their impunity. As a result, the mission of such commissions shifted from one of holding perpetrators legally accountable for political violence to apparently apolitical matters of value affirmation, national healing, and overcoming polarization. In the official discourse, truth commissions were rendered instruments to restore a fractured liberal order.

In Grandin’s reading, Guatemala resisted that mold. He argues that the Comisión de Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH, Guatemala’s 1999 truth commission) determination that the US-backed campaign of state terror that took the lives of hundreds of thousands of Indigenous Guatemalans met the threshold of genocide was an unmistakably political stance, taking into account the country’s history of extreme inequality to condemn the racist ruling class and call for a broad restructuring of the state. But the Guatemalan state met the CEH’s findings with silence, protecting the perpetrators and systemically denying justice to their victims. As Guatemalan scholar Gabriela Escobar Urrutia shows, the memory of the conflict in Guatemala largely settled into the same demobilizing patterns that prevailed elsewhere, promoting a notion of depoliticized, passive victims of an irrational, dehistoricized violence.

The bloodshed in Guatemala reached a scale unseen in the hemisphere. The conflict followed the CIA-backed coup against President Jacobo Arbenz in 1954, one of the seminal US regime change interventions of the twentieth century, which overthrew the democratic revolution initiated with the 1944 election of Juan José Arévalo and, with it, a social project of land reform and democratization in favor of anti-communist military rule and state terror to maintain the country’s profoundly racialized agrarian export economy. By the time the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG) signed a deal with the government on December 29, 1996, the war had taken an astounding toll. The 1999 truth commission reported 150,000 extrajudicial killings and 45,000 disappearances, 93 percent of them executed by the state, and determined that the deliberate, indiscriminate targeting of Mayan indigenous communities for scorched earth operations between 1981 and 1983 under General Efraín Ríos Montt amounted to genocide.

The conflict in Guatemala was protracted and diffuse, and the insurgents were often divided and dispersed across a large and diverse territory. In tiny, densely populated El Salvador, the rebel army stood some ten thousand strong, occupied important swaths of liberated territory in the countryside, and executed a major offensive in the capital city in late 1989 that helped force negotiations. Nevertheless, both nations suffered from US-backed counterinsurgency campaigns that leveled entire villages, massacred civilians, tortured and executed dissidents, and made a grotesque spectacle of state violence. In El Salvador, the 1993 truth commission accounted for some 75,000 deaths and ten thousand disappearances, attributing only 5 percent of the violence to the guerillas.

Relative to the URNG, El Salvador’s Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) entered peace negotiations from a position of strength. The insurgents claimed the 1992 Accords as a victory, achieving the demilitarization of the state, demobilization of insurgents, and a tenuous liberal infrastructure for representative democracy. The FMLN became a successful political party, earning a growing share of legislators and mayoralties throughout the 1990s and 2000s. But the Third World’s revolutionary period had waned, and the neoliberal counterrevolution was ascendent. Socioeconomic reforms to address the civil war’s root causes, such as land distribution and progressive industrial policy, were left off the negotiating table, and while the FMLN gained experience and support at the ballot box, four consecutive right-wing governments implemented devastating free market reforms.

In Guatemala, the deal came later still. By then, the dust of the Soviet Union’s collapse had settled, and many left movements had traded their revolutionary aspirations for nonprofits, socially responsible enterprises, and an abstract concern for human rights. The Peace Accords led to insurgent demobilization and participation in civic life, the restoration of democratic elections, and recognition of indigenous identities and rights. But as in El Salvador, fundamental material inequalities remained unaddressed. Guatemala’s political left — and political parties in general — assumed weaker, more provisional institutional forms.

The result in both nations was a landscape of vast inequality and impoverishment. Neoliberal restructuring carved out a new subordinate role for the region in a US-dominated globalized economy, providing cheap labor for manufacturing assembly plants and raw materials for export. Agro-export and extractive industries remained a pillar of accumulation in Guatemala, where concentration, environmental contamination, and rural evictions to make way for mining and energy megaprojects and monocropping remain a constant source of conflict and displacement. Most of the population, however, was excluded from this model. By 2010, some 60 percent of Salvadorans and 75 percent of Guatemalans worked outside of formal labor markets in activities like street vending, services, construction, and agriculture without access to benefits or minimum wage guarantees.

The growing reserves of young, working-class people excluded from and dispossessed by this predatory model of accumulation were driven into the lowest ranks of US labor markets as criminalized migrant laborers or found subsistence in the region’s burgeoning illicit markets, increasingly dominated by criminal gangs born in US prisons and working-class immigrant neighborhoods and exported to Central America via mass deportation policies throughout the 1990s. And despite the political gains of actors like El Salvador’s FMLN and diverse social movements to defend against the new enclosures, executive and judicial power remained firmly in the hands of the oligarchic bourgeoisie.

This is the postwar political economy that finally gave way in the late 2000s, as neoliberal hegemony suffered a critical blow from the global financial crisis and subsequent recession. In its wake, politics as usual was upended in both nations, preparing the path for the democratic crises each faces today.

The FMLN’s 2009 presidential victory represented a first rupture of the postwar order, a resounding rejection of the prevailing politics of austerity, dependency, and corruption in favor of a social democratic alternative at a time of ascendent left politics across the hemisphere. Starting in the late 1990s, the “Pink Tide” of progressive governments was democratically elected in Latin America, responding to the failures of neoliberalism with robust social spending and redistributive policies. Over two terms (2009–2014 and 2014–2019), the FMLN enacted major social investments and democratic reforms: the administrations removed service fees for public hospitals and created a national network of free, prevention-oriented community clinics; supported domestic agriculture cooperatives; provided free, locally sourced public school meals and uniforms; established services and protections for historically excluded groups including women, children, LGBTQ, and indigenous Salvadorans; mandated government transparency mechanisms; and more. But the political savvy that allowed the party to achieve presidential power would contribute to its downfall. In 2019, the FMLN was overtaken by an ambitious defector backed by an ascendent coalition of bourgeois interests that the FMLN had itself empowered in an effort to weaken the traditional right-wing party and its oligarchic sponsors.

President Nayib Bukele, a millennial publicist and former FMLN mayor whose Palestinian-descended family was part of a favored fraction of commercial capital, dexterously positioned himself as an insurgent outsider. He capitalized on the Right’s aggressive destabilization campaign against left governance to discredit both sides, drawing false equivalencies and styling himself a savior from a hopelessly corrupt political establishment. Where the FMLN failed to transform the daily lives of many Salvadorans with regard to economic insecurity and social violence, Bukele personally promised deliverance.

Bukele’s election proved the second break with the postwar order. He disdained the Peace Accords as a “farce,” casting the agreements as a cynical pact designed to benefit conspiring villains — in his telling, both the guerrillas and the far right — at the expense of a helpless, apolitical, and victimized civilian population. In practice, he steadily reversed their modest gains. In his first year as president, he invaded the legislature with the military to force a vote on a package of loans for security funding. He took advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic to declare a militarized state of exception, triggering a prolonged constitutional crisis as the Supreme Court sought to contain executive overreach. After securing a legislative majority in the 2021 midterms, his party unlawfully fired and replaced the attorney general and all five magistrates of the high court’s Constitutional Chamber, together with hundreds of lower court judges. When Bukele’s secret deal with the country’s leading criminal gangs to reduce the homicide rate collapsed in March 2022 and murders surged horrifically, his party ordered another state of exception, suspending the constitutional rights to due process, legal representation, presumption of innocence, freedom of association, and more. This time, he found no opposition from the courts. The state of exception has been in force ever since.

Bukele’s “war on gangs” saw some 80,000 people arrested in mass, indiscriminate sweeps in the first two years alone. The militarized repression drove many of the street-level gangsters off their corners, providing appreciated relief to the working-class communities targeted for petty extortion and beset by violent turf wars. This apparent success, which conceals the administration’s complicity with high-level narcotrafficking and organized crime, won Bukele enough goodwill to rally him through a constitution-defying reelection bid in February. At the same time, he put his advertising skills to work, projecting an international tough-on-crime image and honing his brand as a far-right icon. He headlined at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in February 2024, sat for several Tucker Carlson interviews, and has aggressively courted the US MAGA cohort, hosting Carlson, Donald Trump Jr, and soon-to-be-disgraced congressman Matt Gaetz for his June 2024 inauguration for an unconstitutional second term; Gaetz later established the “US–El Salvador Caucus” in Congress to promote Bukele’s agenda and image in Washington.

In this time, El Salvador gained the highest incarceration rate in the world. Many prisoners have been held for nearly three years without trial, denied access to council, family visits, medical attention, and even sufficient food, while some are subjected to violence and torture by authorities. Human right groups have identified at least 26,000 innocents among the detained, with over 360 deaths confirmed behind bars, many due to medical neglect, others indicating homicide. Court orders for release on humanitarian grounds or otherwise are routinely ignored by prison authorities.

Following Bukele’s 2019 presidential victory, important oligarchic interests defected to his camp, while those right-wing politicians who refused were driven into exile or imprisoned. But Bukele’s true enemy was always the Left. He began with blanket prosecutions of former FMLN cabinet members, elected officials, and party leaders on trumped-up corruption charges. Under the state of exception, the dragnet widened to target former combatants and social movement leaders, including organized communities defending their territories from government-backed developers and extractive ventures.

As the cash-starved administration moves forward with mass layoffs and austerity, public sector union leaders have been met with repression and imprisonment; over 22,000 workers have been fired since 2019 and at least sixteen union leaders have been imprisoned since 2022. Together with informal street vendors, these sectors are on the front lines of the regime’s strategy of accumulation by dispossession. Having failed to engineer an economy around Bitcoin after making the volatile cryptocurrency legal tender in 2021, he is using his police state to purge the nation’s coasts and urban centers of the poor to make way for real estate speculation, international tourism, and natural resource exploitation. Following Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s recent visit, Bukele pitched a new, if improbable, venture: renting out his penal system to the United States to warehouse deportees of any nationality and even US citizens.

Bukele responds to critics by pointing to his persistent popularity, having secured his reelection in February 2024 with 83 percent of the vote. While the president’s unparalleled international communications and advertising strategy doubtless plays an important role in sustaining his support, much of the population was willing to countenance the repression in exchange for a respite from the gangs’ torments. That support, however, is not unconditional. In the February 2024 general elections, Bukele’s legislators and mayors received significantly fewer votes than he did, even after they rewrote the entire postwar election system to favor their party and effectively eliminate the opposition. Since then, his “New Ideas” party, which holds a supermajority in the legislature and 64 percent of municipal governments, has been plagued by corruption scandals, while discontent rises in the face of a spiraling cost-of-living crisis and the recent reckless, unpopular decision to overturn the nation’s historic 2017 ban on metals mining. By now, however, little remains of any democratic avenues for an electoral challenge.

The 2010s saw a series of challenges to decades of state silence, suppression, and denial of the war’s atrocities, and to racist, corrupt elite rule in Guatemala. Perhaps most emblematically, these challenges included the 2013 trial of General Ríos Montt for genocide and the mass mobilizations of 2015 that toppled President Otto Pérez Molina amid a metastasizing corruption scandal. Both events were historic achievements against impunity in the country, while also revealing the sharp limits of justice under the postwar system. These contradictions have culminated with the presidency of Bernardo Arévalo, elected in 2023.

In 2001, surviving communities and human rights organizations filed suit against General Efraín Ríos Montt, whose bloody tenure as de facto president of Guatemala from 1982 to 1983 was bookended by military coups. The suit cited the killing of 1,771 indigenous Maya Ixil Guatemalans and the forced displacement of tens of thousands more under his leadership as commander in chief, for which President Ronald Reagan lamented the general was “getting a bum rap.” But Ríos Montt was shielded from prosecution as a sitting congressman with the far-right Guatemalan Republican Front party that he founded in 1989. It was not until the expiration of his term in 2012 that Attorney General Claudia Paz y Paz brought an indictment against him for genocide and crimes against humanity. The case went to trial in 2013.

The prosecution, which also targeted former military intelligence director José Mauricio Rodríguez Sánchez, was a dramatic watershed event in Guatemalan history, a long-sought reckoning for the communities and organizations that faced the brunt of state terror and a radicalizing moment for a younger postwar generation confronting their history for the first time. On May 10, 2013, the eighty-seven-year-old Ríos Montt was convicted and sentenced to eighty years in prison. But the victory was short-lived. Ten days later, the Constitutional Court annulled the proceedings. The retrial finally began in January 2015 but had not concluded at the time of the dictator’s death in April 2018.

By then, the country had experienced another bittersweet triumph. In 2015, an investigation by the UN-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG, in Spanish) unearthed an elaborate conspiracy of customs fraud that ended up implicating both Vice President Roxana Baldetti and President Otto Pérez Molina, a former member of the US-trained Kaibiles special forces that perpetrated notorious wartime massacres and atrocities. Public outrage was galvanized into the country’s biggest mass protest movement since the October Revolution of 1944. Amid weeks of historic mobilizations, both Baldetti and Pérez Molina were successively stripped of immunity, arrested, tried, and eventually convicted for fraud, money laundering, and illicit gain.

Commentators heralded a “Guatemalan Spring,” and the capital city was giddy with celebration. But the liberal anti-corruption framing of the movement, which was led by largely urban, ladino (nonindigenous identifying), middle-class Guatemalans, limited the directions in which popular energy could be channeled. Implicit in the calls for the ousting of bad apples was the notion of a functioning system that needed only to be purged of its nefarious elements in order to restore proper governance. This vision contrasted starkly to contemporary Indigenous movements’ calls for the refounding of Guatemala as a plurinational state through a popular constituent assembly, in the style of Ecuador or Bolivia. After the crowds dispersed, voters elected a military-backed comedian, Jimmy Morales, to replace Pérez Molina. When the CICIG opened investigations into Morales for illicit campaign financing, he declined to renew the commission’s mandate.

The ensuing years saw a massive backlash against judges, prosecutors, journalists, and activists. Attorney General María Consuelo Porras, whose first term began in 2018 and was renewed in 2022, dismantled the existing anti-corruption infrastructure and persecuted dissidents. Dozens of judicial and media workers have since fled into exile, while others, like veteran reporter and publisher Rubén Zamora, were imprisoned. It was in this climate of escalating censorship, criminalization, and repression that Bernardo Arévalo was elected president in 2023.

The son of the country’s first democratically elected president, Arévalo ran as an unlikely candidate with the small, center-left Semilla party. After favored popular challenger Thelma Cabrera, a Mayan Mam indigenous candidate who ran on a platform for a popular and plurinational Constitutional Assembly, was barred from the race by the same practices of lawfare that have targeted activists, journalists, and jurists, the Semilla ticket handily won in both first- and second-round voting, buoyed by the profound historical resonance of the Arévalo name. Semilla’s base was largely young, urban voters, including many politicized by the Ríos Montt trial, but the party also earned support in rural, indigenous sectors. This backing proved critical when Porras led efforts to undermine the results and suspend the party’s credentials. Powerful indigenous organizations — which, along with campesino (peasant) organizations, are generally more relevant political actors in Guatemala than conventional labor unions — convened an indefinite national strike, mobilizing roadblocks across the country and gathering in the capital to rally for the president-elect when opposition lawmakers plotted a last-ditch attempt to prevent the inauguration.

Now in office, Arévalo faces deliberate obstruction and destabilization by an enemy attorney general that he has thus far been unable to remove, an adverse Supreme Court, and a restive military. With a minority in Congress and the judicial branch captured by the Right and its associated criminal elements, the first year of the Semilla presidency has been characterized by a sense of paralysis. Instead, Porras has escalated her attacks, expediting charges against Semilla politicians, including ordering the arrest of a cabinet member and crusading to strip Semilla of its legal status. The government that promised transformation appears increasingly uncertain and anemic.

In both countries, the tenuous liberal democratic framework established by the 1990s Peace Accords is long exhausted. The FMLN, for all its policy efforts to halt the advance of neoliberal reforms, watched helplessly as its mandate was eroded by right-wing blockades in the legislature and obstruction in the courts. Bukele has had no such misgivings. To the contrary, he has unilaterally remade El Salvador’s political system in his favor from above. Whatever his popularity, his is a deeply anti-popular project to reap personal gain and glory at the expense of El Salvador’s working majorities.

As Guatemala’s constitutional crisis reaches a critical conjuncture, Arévalo, too, finds himself up against the limits of the postwar system. In his imagining, the president is fighting to recoup Guatemala’s democracy from capture by elites. Like the anti-corruption movement that preceded him, his loyalty to the constitution and the liberal order limits his repertoires of response when confronted with a hostile bureaucracy and the anti-liberal commitments of the radical right. If he remains unwilling to challenge the structures built to favor capital and its guard dogs, he will fall victim to them. Guatemala’s democracy cannot be restored from above. Instead, as many of the country’s indigenous leaders have long understood, it must be remade collectively from below.

The political systems installed in the region were the product of the prevailing balance of forces between national liberation movements, oligarchic elites, and ascendent transnational capital. As a result, they favored the reproduction of inequalities imposed with neoliberal restructuring. In the present period of prolonged crisis, these frameworks are being refashioned again. For better or for worse, the form they take will be the result of struggle.

This dilemma is not unique to Central America. In the rubble of neoliberalism, responses to the converging global crises pit collective, liberatory movements for the commons against reactionary, preliberal forms that are increasingly dragging the feckless center into their orbit. The task of the Left is to look beyond the failed institutions of the present and imagine more just and inclusive futures. As El Salvador’s example shows, the cost of failure is high.

Great Job Hilary Goodfriend & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.