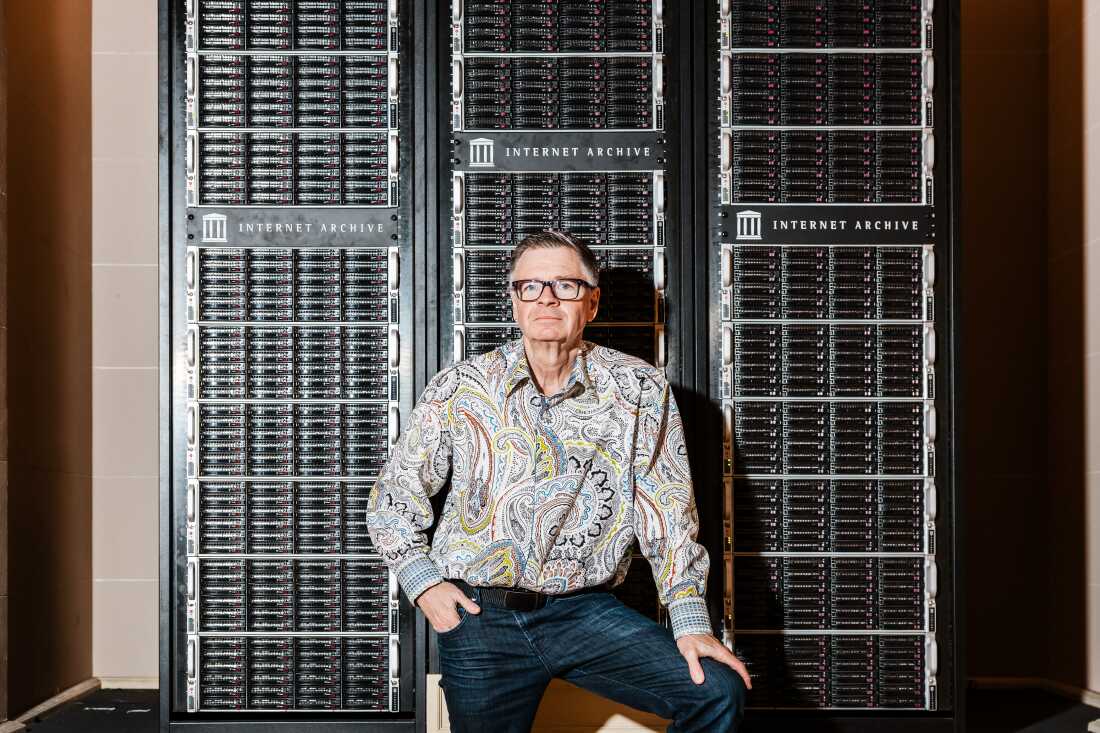

Humming along in an old church, the Internet Archive is more relevant than ever

March 23, 2025

Trump Called ‘Pathetic’ for Demanding Apology From Maine Gov. Janet Mills | Common Dreams

March 23, 2025

The Liberal Party of Canada is one of the most successful political parties in the world. It exists to win elections — which it does — by absorbing elements from the center right and center left, all while staying firmly within the broadly centrist (or, as they’d say, “pragmatic”) territory it has occupied for decades. Consequently, the Liberals have governed Canada for most of its history.

Just months ago, the party was trailing its Conservative rivals by more than twenty-five points. Now, heading into a general election, it’s once again favored to win — and to face the challenge of Donald Trump.

At the helm is the new face of the Liberals and Canada’s current prime minister, Mark Carney: a technocratic elite who once worked for Goldman Sachs and served as governor of both the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England. Months ago, commentators — including myself — argued that he was out of step with the moment. He couldn’t win the Liberal leadership, could he? He did, resoundingly. He couldn’t revive party fortunes, could he? So far, he has.

At first glance, Carney didn’t seem to fit the angry, populist, anti-elite mood that Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre had tapped into with his rousing — if hollow — pro-worker, antiestablishment, and government-slashing crusade. Carney looked like a mismatch for the moment: a stolid, down-tempo cosmopolitan, the kind of figure that MAGA politics and contemporary Canadian conservatives are primed to make mincemeat out of. He was Davos Man — the quintessential technocrat, a poster child for populist ire. Carney seemed like a perfect target for all the anxieties and frustrations that have been building for years that Poilievre had worked so hard to leverage.

Then, all of sudden, Carney’s demeanor and resume began to look like assets. With Trump threatening tariffs — and annexation — the stakes shifted. Canada no longer seemed to want the MAGA-lite fisticuffs as much as a steady hand. Carney became, for lack of a better metaphor, a kind of national father figure, offering calm amid chaos. Without Trump, Carney’s rise is doubtful. Absent the rally-around-the-flag effect that accompanies an external threat — and the potential incumbency advantage that entails — he might have entered the race as a damp squib. Maybe Poilievre will still win once the election is thoroughly underway, but for now, Carney is looking good in the eyes of voters.

Never mind the policies Carney is offering: killing the consumer carbon tax, reconsidering the cap on oil and gas emissions, ending the planned increase to the capital gains inclusion rate — these are so Tory friendly that Conservatives are complaining that he’s cribbing from their notes. It doesn’t matter. Carney is not the angry, pugilistic Poilievre. He projects levelheadedness — the kind of presence one might prefer in the face of US-induced chaos in the maple kingdom. He and his party might be able to ride that vibe all the way back from the edge of electoral oblivion on which they sat just weeks ago.

The thing about winning an election, of course, is that you then have to govern. Trump has said nothing directly about Carney’s win; he has dismissed Poilievre as “stupidly no friend of mine,” told Fox News it’s “easier to deal actually with a Liberal,” and added that “maybe they’re going to win. . .”

Trump will still be in the White House if Carney wins, and he’ll still be prosecuting a tariff war — the latest round of threatened duties is due April 2 — or worse. He’ll still have designs on hemispheric domination, like a demented James Monroe or William McKinley. And Canada, the would-be “cherished fifty-first state” will still be in his way. If the Liberals do cash out on a reprieve from populist hostility, they’re likely to face its return — with consequences — on both sides of the border.

Talking to former Tony Blair strategist Alastair Campbell and Trump press secretary Anthony Scaramucci, Carney embraced the label of “global elitist,” adding, “Well, that’s exactly what we need.” The idea here is that being able to work the global circuit — state leaders, industry heads, the people who make the capital flow and the trains run on time — is an advantage. Carney obviously knows banking, state and private; he knows trade; he knows how networks operate. This is why he is being cast as someone who can play chess in four dimensions on multiple continents.

But this projection, reassuring as it may be in the abstract, may falter in direct confrontation with Trump, because the president refuses to play chess — or even checkers. Trump operates, as Sigmund Freud would say, on the id: he is emotional, impulsive, unbound. It’s a disposition that gets him labelled as “mercurial,” but that often obscures a more rational, if deranged, will to power — and contempt for domestic and international rules alike. This is a president who invokes national security concerns — “fentanyl” — to override trade agreements, who uses the “will of the people” to run roughshod over the United States Congress, judiciary, and Constitution. You don’t outmaneuver that with technical skill alone.

If Canada’s rally-around-the-flag moment abates — as such moments tend to do — and Trump’s tariffs trigger a recession, compounding the country’s persistent affordability crisis and the lingering trauma of the pandemic, things could get, as Trump would put it, very, very, nasty. Carney would then be left dealing with the same political landscape that rendered former prime minister Justin Trudeau persona non grata and paved the way for his own rise.

In short, the tailwinds that lifted Carney’s sails could quickly become headwinds as Canadians give up the tariff-era equivalent of the early pandemic practice of banging pots and pans in honor of health care workers.

Of course, Carney and his party will take that deal — better to win and face difficulties than not win at all. But a victory brings its own burdens: heightened expectations, the pressure to navigate a national crisis, and the need to redefine Canada’s place in the world — particularly its long-term trade and defense relationship with the United States.

The same twist of fate that elevated Carney and made him a contender for staying in office may soon turn on him — as may the country and its fickle voters, who are all too happy to give a guy a chance . . . until they’re not.

Great Job David Moscrop & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.