By the Time We Get to Phoenix

March 21, 2025

Trump says Education Department will no longer oversee student loans, ‘special needs’

March 21, 2025Elon Musk and Donald Trump are attempting to transform the architecture of the federal government. The American state under their influence is not merely a vehicle for broad capitalist governance but a tool for the personal enrichment of individual business elites.

Many of DOGE’s cuts to public spending thus far remain more performative than transformative, but the intent is clear: to gut the regulatory apparatus, loot public resources, and erode one of the state’s core functions — providing the conditions for capitalism to reproduce itself. A truly transformative shift, such as a major Medicaid cut in Congress, would mark a decisive turn in this trajectory. This is not simply an assault on the administrative state; it is also an attempt to replace a system geared toward the functioning of capitalism as a whole with one that privileges specific capitalists.

There are lessons to be drawn from Marxist theory, which, in its long and unshakable commitment to being right about this sort of thing, has rarely missed an opportunity to make a rather big deal about the difference between the capitalist system as a whole and the agents inside it.

Capitalism, for all its routine savagery, requires a basic framework to function: some degree of competition, costly public investments in education and physical capital, the containment of externalities, a semiregulated financial system, and control of the most predatory business practices. The state has traditionally played a crucial role in maintaining these conditions, not out of benevolence but out of necessity.

Marxist theories of the state have long recognized that, for capitalism to sustain itself, the state must act on behalf of capitalism as a system, not merely at the behest of individual capitalists. When the state abandons its role in overseeing capitalism’s long-term viability and instead caters narrowly to specific firms (or individuals), the results can be ruinous.

Marxist state theory, in its more opaque register, dubbed this “relative autonomy.” Marxists have a certain weakness for what the Greek political theorist Nicos Poulantzas called grand and terroristic concepts, but the idea has its force. If a state fails to carve out even a modest independence from its own small-minded capitalists, it neglects the very conditions capitalism needs to endure.

When capitalists govern directly, they tend to be myopic, dictating the state’s execution of their own narrow and immediate interests. Governments that are directly commandeered by capitalists tend to hollow out the conditions of accumulation. Over time, such governments encounter immense negative feedback and may get selected out of history. To survive, the state requires some relative autonomy from capitalists.

In the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx described the capitalist state as “a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.” But why the “whole bourgeoisie” rather than a narrow section? The answer lies in institutional durability. When governments become tools for the parochial ambitions of a handful of eccentrics, they flounder. Drained of their relative autonomy, such governments make bad decisions and tend to face selection pressures. When they excise broader regulatory, investment, and spending needs, they incur sharp political and economic costs, often turning their states into stagnant and politically brittle regimes. This may force them to adapt under pressure. If they fail to course correct, however, they risk being replaced by political challengers. Even if they endure, they may be marginalized, eventually outcompeted by more stable, productive states on the global stage. Sooner or later — sometimes later — political and economic life drift back into rough alignment.

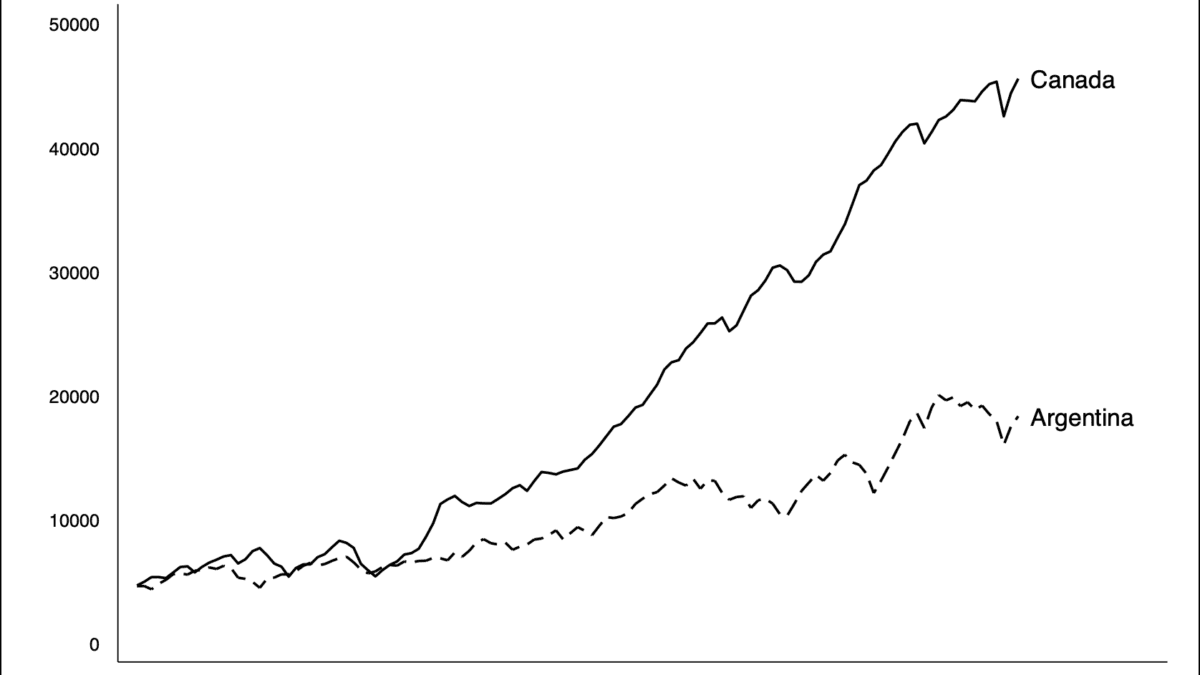

A bit of potted history clarifies the stakes. At the turn of the twentieth century, Argentina and Canada were both relatively high-productivity economies with similar resource endowments. At the time, it was far from clear which nation would develop more swiftly. As GDP statistics below show, in the first third of the century, Argentina seemed just as poised to become an industrial powerhouse by century’s end. But their political trajectories diverged sharply.

In Canada, the state maintained some relative autonomy from capital, enabling it to provide the basic structure of state investment, regulation, and spending — conditions essential for sustained capitalist expansion. Argentina, by contrast, saw its state captured outright by specific capitalist factions, who raided it for short-term advantage, unburdened by concern with the system’s long-term stability. Its political institutions became instruments of patronage, stunting any prospect of dynamic accumulation.

This logic found its clearest expression in the Roca-Runciman Treaty, an agreement between Argentina and Britain that heavily favored British business interests (especially in the meatpacking industry) and Argentine agro-exporters (especially large cattle ranchers). Argentina’s economy remained shackled to raw material exports — good for some of the large landowners, but stifling industrialization. This is only one example, but the greater the direct influence of specific economic elites, the weaker the state’s autonomy became. And the results were plain: Argentina drifted into economic dysfunction, trapped in a fragile political model, while Canada plodded along, growing at a steady clip.

The breaking point for Argentina came in 1930 with its first military coup. This marked the end of democratic rule and set a precedent for military intervention that would recur throughout the twentieth century. Before 1930, democracy in Argentina and Canada, as measured by the Varieties of Democracy data shown below, was roughly comparable. But after the coup, Argentina’s democratic institutions collapsed. They did not recover until the end of military dictatorship in the early 1980s.

Economic data shown above tell a parallel story: GDP per capita in the two countries had moved in near lockstep until this divergence. While GDP is an imperfect proxy for standards of living, it remains an instructive measure, and here its lesson is stark — Argentina’s economic trajectory faltered as its political institutions did, while Canada’s continued upward. The selection mechanism in Marxist state theory finds empirical support in this history: states whose political superstructures neglect the needs of capitalism tend to falter. In Marxist lingo, when the superstructure stopped reinforcing the base, the base crumbled. Through this lens, Argentina’s successive coups can be interpreted as a trial-and-error process that only stabilized when elite governance moved beyond the exclusive dominance of a single economic faction.

This divergence in national trajectories was no accident. It reflects a selection mechanism often overlooked in Marxist state theory: a state that fails to secure the conditions for capitalist accumulation risks unraveling the system itself. Short-term plunder may enrich a handful of elites, but it sabotages capitalism’s broader reproduction. While capitalism’s long history suggests that political superstructures tend to fit themselves to economic bases, there is no guarantee that they will be functional at any given moment. As with any selection mechanism, some organisms thrive, others wither and are cast aside.

The United States now faces a similar inflection point. With Musk and Trump at the helm, the state is becoming a plaything for a narrow slice of the elite. If history is any guide, this is not a recipe for some deepening of American capitalism — it is a formula for its unspooling. Marxist theories of the state are appealing precisely because they are ambitious enough to offer predictions. In my view, a version of the theory can accommodate immense democratization and socialist reform. But one straightforward prognosis Marxist state theorists would offer to Trump’s America is that it is a fantasy to believe that a narrow patronage state can indefinitely accommodate the wide-ranging requirements of contemporary capitalism. The theory suggests that dysfunction — and the eventual failure of DOGE and similar projects — is the most likely outcome.

As the historian Adam Tooze noted recently, Musk is hardly the first to pour vast sums into political causes. The difference is that, historically, the return on political investment was more diffuse. In US history, at least, no capitalist had yet had the organic intellect to simply install themselves copresident. Perhaps prior elites hesitated for a reason.

My suspicion is that this project will ultimately unravel — that democratic pushback, coupled with clobbering economic feedback, will forestall a fate akin to Argentina in the 1930s. But even if the capitalist state does eventually clatter back into line with the functional requirements of the economy, nothing precludes a prolonged and idiotic period of dysfunction while it is run at the behest of a small fellowship of businessmen.

Great Job David Calnitsky & the Team @ Jacobin Source link for sharing this story.